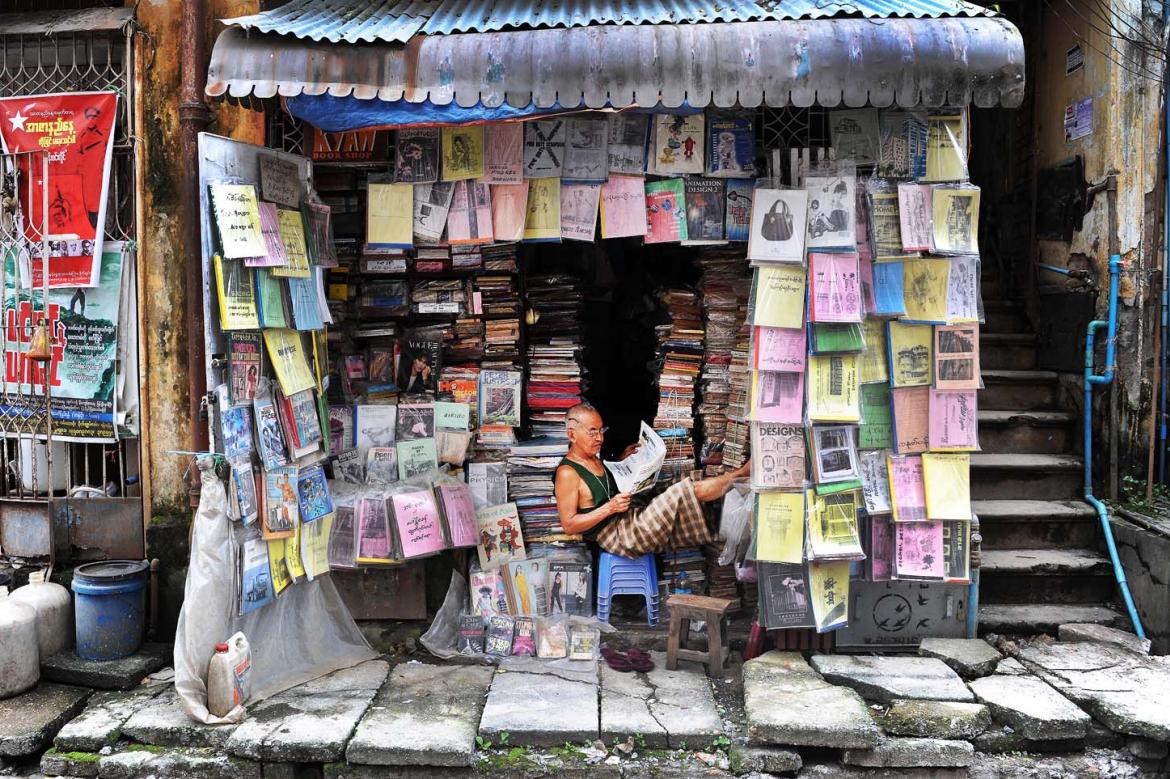

Performance art emerged in Yangon in the 1990s and flourished under junta rule in the late 2000s but has since gone into decline.

By MRATT KYAW THU | FRONTIER

IN 1997, during the days of military rule, a man took a stroll along Pansodan Road in downtown Yangon with barbed wire wrapped around his head. Shocked pedestrians stopped and stared at what was one of the first public exhibitions of performance art in Yangon.

The man clad in barbed wire was the artist Nyein Chan Su and Pansodan Road was the stage for his dramatic – and pointed – debut as a performance artist.

“Have you seen the world from behind barbed wire? We had been behind this [barbed wire] for a long time at that time,”said Nyein Chan Su, 44, a prominent multidisciplinary artist also known for his vivid acrylic abstract paintings who graduated from the State School of Fine Art in Yangon, in 1994.

When Nyein Chan Su went walkabout in barbed wire, performance art was largely hidden in Myanmar, and for good reason. A repressive junta also ensured that exhibitions touching on politics never saw the light of day, though fashion shows were becoming increasingly popular in the late 1990s.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Under Senior General Than Shwe’s regime, much “political” art was driven underground. Performance artists, and their often bizarre and enigmatic allusions to the prevailing circumstances, were no exception.

jtms_installationart-05.jpg

Artist U Aung Myint at Yangon’s Inya Gallery, which he owns, on March 16. (Theint Mon Soe — J | Frontier)

The junta’s rigid, pervasive censorship system meant that many galleries could not exhibit publicly and some exhibitions took place in artists’ homes.

Another pioneer performance artist, Aung Myint, 72, recalled the challenges of life under the junta.

“At that time, we just revealed our emotions and beliefs on politics directly and sometimes indirectly, but not in public,” he told Frontier.

Aung Myint’s first performance art was conducted at Chaung Tha beach in Ayeyarwady Region in 1996, exploring the theme of death. His audience comprised just a few friends.

Aung Myint, a multidisciplinary artist who graduated with a degree in psychology from Rangoon Arts and Science University in 1968 and opened the Inya Gallery in 1989, continued to create performance art until the U Thein Sein government took office. Today his art work is focused more on painting.

The emergence of performance art in Myanmar in the late 1990s was encouraged during visits by artists from Japan, Malaysia and Hong Kong, and some from Europe. They conducted secret workshops that inspired many Myanmar artists to explore ideas about using their bodies as the medium in performances.

artactivismmilko-7.jpg

Victoria Milko | Frontier

Aung Myint said the satisfaction of performance art came from the artist’s simultaneous roles as actor, director and script. “It’s not like making movies, which is a planned process,” he said. “Performance art is more active and effective; that’s why I became involved,” he said.

There was little public appreciation of performance art in the late 1990s. Artists who did performance art in the street were called “crazy” or “fools”, said Aung Myint, adding that “performance art is with intention and without intention”.

Aung Myint, a self-taught artist, has had solo exhibitions in Tokyo, New York, Hong Kong and Singapore, as well as Yangon. One of his works is featured in the Guggenheim Museum in New York. “White Stupa Doesn’t Need Gold,” in acrylic and gold leaf on canvas, was created in 2010.

Performance Art booms

Following its emergence in the 1990s, performance art grew slowly and stayed mainly out of sight. There were some performances after the protests in 2007 known as the Saffron Revolution. Performance art began to take off in 2008, when many foreign artists visited Myanmar. Some conducted workshops in performance art.

A new generation of performance artists began to emerge between 2008 and 2010. Ahead of the trend was Moe Satt, 34, who launched his career as a performance artist in 2005.

“Those years are the climax of performance art, we can say. Lots of foreign shows regionally, and even three exhibitions in one year. Some friends from other countries said that Myanmar is too active in performance art especially at that moment,” Moe Satt told Frontier, referring to the late 2000s.

artactivismmilko-3.jpg

Nyein Chan Su displays a photo of his “barbed wire” performance art exhibition, which was held in downtown Yangon in 1997, when Myanmar was under military rule. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

The emerging generation of performance artists had a breakthrough in 2008 when the junta’s censorship authorities for the first time approved an application for a performance art show in Yangon.

After a while, performance artists did not bother to seek approval for their shows. Moe Satt was detained after an unauthorised performance in Mandalay in 2012 but was released without charge.

By about 2010, some performance art was being presented as pop-up shows.

However, Aung Myint thinks some young performance artists are opportunists.

“They say performance art is so easy to do but I think they can’t express what’s on their mind. They think that by calling themselves performance artists they can go to foreign countries and earn dollars easily,” he said.

Female artist Zon Sabal Phyu, also known as Zon C, acknowledged that some performance artists were opportunists, “but not all”.

Zon Sabal Phyu has been focusing on her art since the November 2015 election, when she was the campaign manager for Naw Susanna Hla Hla Soe, who won an Upper House seat in Yangon Region for the National League for Democracy.

The number of performance art shows has declined since the election and members of the artistic community told Frontier on condition of anonymity the NLD government had pressured some artists not to focus on themes that were critical of the former military regime.

“Actually, performance art is not about revenge; it’s all about reminding people of the past,” said Nyein Chan Su.

Performance Art declines

Before the NLD took office a year ago, considerable foreign funding was available to support the arts in Myanmar. There were many exhibitions and it was common for them to be sponsored by international non-government groups.

“Europe, especially, wanted to help the artistic community; it was related to the transition,” Moe Satt said.

“Later, it seemed like they thought Myanmar had changed and there were no more funds and grants,” he said, adding that that was one reason why there have been less performance art shows since Myanmar transitioned to the NLD government.

Moe Satt organises performance art shows but business is far from booming.

In the past he could arrange at least one show a year, but is now limited to planning one show every three or four years.

nswks-installation-5.jpg

Members of the public attend an installation art event in Mahabandoola Park in downtown Yangon. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Zon Sabal Phyu said one of the reasons for the decline in performance art was a decision by the Thein Sein government to divert funding intended for the arts and spend it on development.

“When I asked them [government], they said that they had allocated so much for the arts in the previous term, but it had no impact on development. That’s why they used that money for development,” she said.

Zon Sabal Phyu said despite Myanmar having “so many artists” they received little support.

“There’s no one to create awareness about performance art among the public; that’s one reason for the decline in performance art shows,” she said.

Artists are closely watching the NLD government for any developments involving increased support for the arts. There has been some encouragement, as the Yangon regional government has permitted some exhibitions in public parks.

Aung Myint said that under the junta, art was not about personal abuse.

“We fought the government because they pressured us, they attacked our art. If the government controlled and rejected the art, we had to fight back for the sake of art.”

TOP PHOTO: Performance art emerged in Yangon in the 1990s and flourished under junta rule in the late 2000s but has since gone into decline.