On the centenary of King Thibaw’s death in lonely exile in India, his descendants are ramping up a campaign to have his remains returned to Mandalay, the last royal capital.

By OLIVER SLOW | FRONTIER

MORE THAN 130 years after British troops marched into Mandalay, toppled the Konbaung dynasty and ousted the royal family abroad, the body of Myanmar’s last king lies in a little-known plot in western India, overlooking the Arabian Sea.

After capturing the royal capital, the British exiled Burma’s last king, Thibaw, and his family to the Indian port city of Ratnagiri, in the state of Maharashtra.

Thibaw died there, aged 57, on December 16, 1916, one hundred years ago this week. He was buried in a small grave alongside his junior queen Supayagalae, who died in 1912.

His chief queen, Supayalat, and the couple’s four daughters were allowed to return to Burma nearly three years after his death.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“They spent most of [the rest] of their life in misery, in a very sorrowful state in another country,” said U Soe Win, Thibaw’s great grandson, at an event hosted at U Thant House in Yangon on December 8 to commemorate the centenary of Thibaw’s death. “I explain to any of my friends who go [to Ratnagiri] to go and see Thibaw Point.”

It was here that Thibaw would come each evening to reflect on what had happened to him and his family.

“When the sun went down, he stood there longing to go back home. Every evening he made that journey,” said Soe Win.

When Thibaw died, his family, led by Supayalat, had requested permission for his body to be returned to the Royal Palace in Mandalay but the British refused.

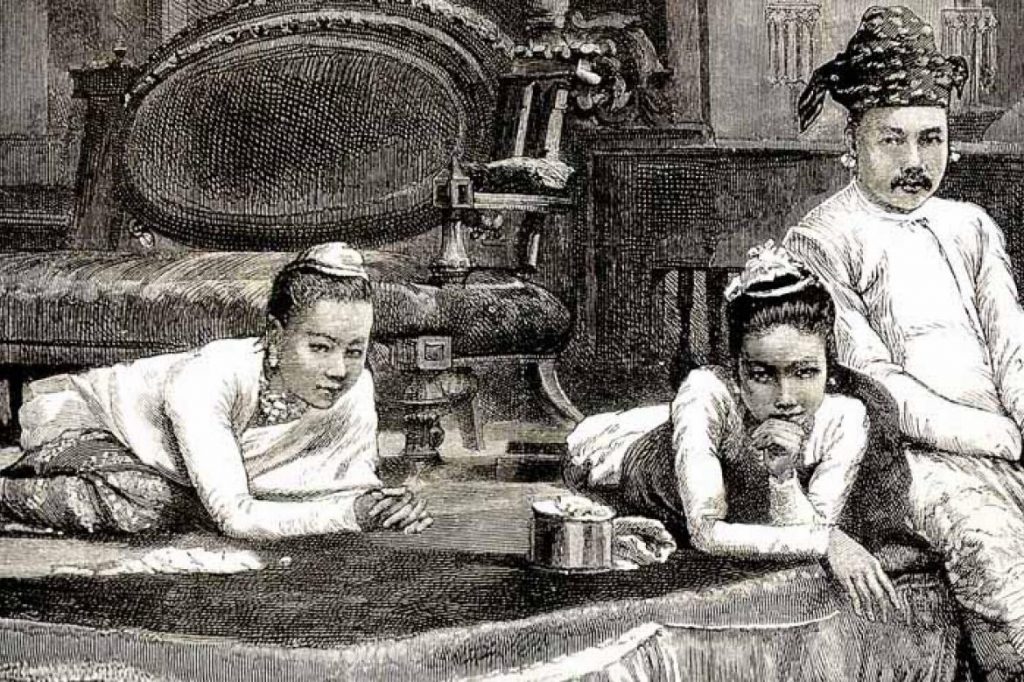

dsc_8973.jpg

King Thibaw and Queen Supayalat. (Supplied)

When the British gave permission for Supayalat and the couple’s four daughters to return to Burma a few years later, they asked that the bodies of both Thibaw and Supayagalae be allowed to join them, but again the British refused.

As the family was making its preparations to return “word arrived … from the government in Burma that it would not under any circumstances permit the mortal remains of the late king and junior queen to be brought to the country”, wrote author Ms Sudha Shah in her 2012 book The King in Exile.

“The explanation provided to the government in India was that the ‘possibility of using them symbolically, to stimulate … political aspirations of an exceedingly dangerous character would be ever present, and they would be a never ending source of extreme anxiety’.”

The family arrived back in Burma in April 1919, and was granted a “modest-sized” home in Rangoon with views of the Shwedagon Pagoda.

“Mandalay was where [Supayalat’s] heart belonged, not to this very anglicised city of Rangoon, which was nothing like the Burma she remembered. But she accepted that it was here that she would have to live out the rest of her days,” wrote Shah.

She died in 1925 and was buried in a tomb south of Shwedagon Pagoda, where her body remains.

As the royal couple’s four daughters grew older, it was the youngest, Ashin Hteik Su Myat Phaya Galae (the so-called “Fourth Daughter”) who was most critical of the colonialists. In 1930, she made written claims for her father’s kingdom.

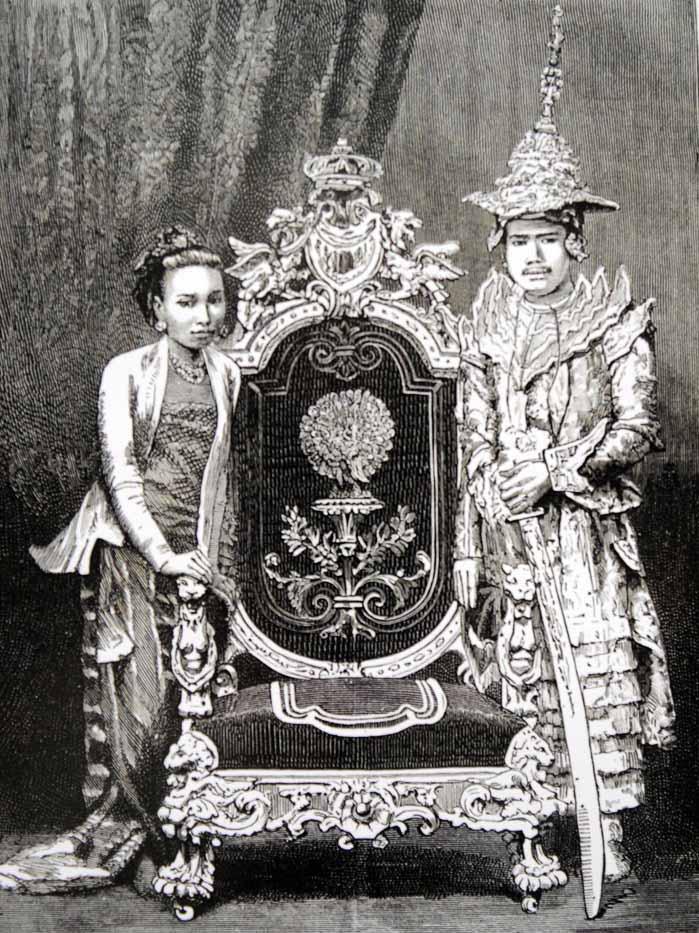

dsc_8981.jpg

The graves of King Thibaw and Queen Supayagalae, in Ratnagiri, India. (Supplied)

The British tired of her, calling her the “Rebel Princess”, and by 1932 she and her six children were sent to Moulmein (now Mawlamyine, in Mon State) where they hoped she would quieten down.

Speaking at the centenary event, her daughter, and Thibaw’s granddaughter, Princess Hteik Su Phaya Gyi, a charismatic 94-year-old, spoke fondly of their home in Moulmein.

“The house the British gave us was like a mansion. Four big bedrooms, two and a half acres, full of fragrant flowers blooming, and the backyard was full of vegetables. It was a grand house. My mother passed away there; I think her heart was broken,” she said.

Hteik Su Myat Phaya Galae died there in 1936.

A forgotten king

Although some of Burma’s most celebrated kings, including Alaungpaya, Anawrahta and Thibaw’s own father, King Mindon, are remembered fondly by the Myanmar public, granted statues in Nay Pyi Taw and roads named after them across the country, there is little recognition of Thibaw in the history books.

Speaking at the centenary event, historian U Thant Myint-U said the British had created a “myth” about Thibaw in order to further their claims that his kingdom needed to be overthrown. In reality, they wanted to take advantage of the economic opportunities on offer in the country.

“The myth of King Thibaw is quite well known; that he was an ogre, that he was despot, that he was a drunkard. Unfortunately, a lot of these myths about the king, that he was a uniquely weak individual, that he was someone who was not up to the task of government, are things that have seeped into the popular imagination in this country,” said Thant Myint-U.

In reality, Thant Myint-U argues that Thibaw and his advisors were reformists on a parallel with other strong leaders at the time, including in Japan, Egypt and Siam (now Thailand).

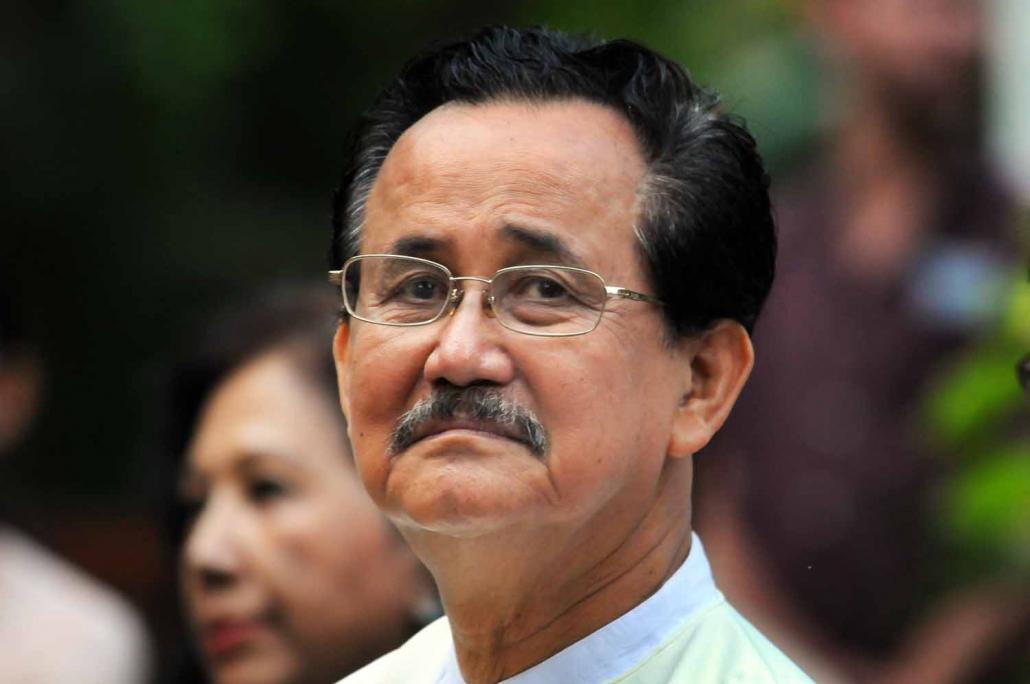

dsc_9077.jpg

Princess Hteik Su Phaya Gyi, King Thibaw’s granddaughter, and daughter of the royal couple’s youngest child Ashin Hteik Su Myat Phaya Galae. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

One of the most famous lines created by the British about Thibaw painted him as a “gin-soaked tyrant”.

“The king was repeatedly offered alcoholic beverages during the trip [from Mandalay to Ratnagiri], which he invariably turned down; perhaps now the officers accompanying him questioned the validity of the endless press reports that had painted him a drunkard,” Shah wrote.

British filmmaker Mr Alex Bescoby, who is filming the documentary “Burma’s Lost Royals”, which is due for release in 2017, told Frontier that the British narrative about Thibaw is “probably one of the most successful propaganda campaigns of all time”.

“A lot of the propaganda was absorbed into the psyche and into textbooks, and his apparent weakness was cited as a reason that the kingdom fell, when you could probably say that whoever was on the throne wouldn’t have been able to deal with the British forces,” he said.

As an example of how little Thibaw is regarded, Bescoby said he was visiting a monastic school in Mandalay while filming the documentary.

“We were running around looking in history books for any mention of Thibaw. Mindon was there, Alaungpaya was there, Anawrahta was there, but we couldn’t find anything on Thibaw. Eventually we found a page, where he’s mentioned in one sentence.”

Time to return?

Bescoby, who has formed a close bond with Thibaw’s descendants in the two years since he started work on the documentary, said there is a difference of opinion within the family as to whether now is the right time for Thibaw’s body to return to Myanmar.

“I think most of them agree that it would be nice to close that loop of history; to bring him home because this is where he belongs; he wanted to come home, his wife wanted him to come home. The difference of opinion is whether now is the right time. Is it a way of bringing the country together?”

Both Soe Win and Hteik Su Phaya Gyi believe that now is indeed the right time for the king’s body to be returned. On December 13, Bescoby was to join Soe Win and other members of the family on a trip to India, where they planned to visit Thibaw’s palace in Ratnagiri.

“We will go there and pay respect, not only as a member of the royal family but as a representative of the people here,” Soe Win told Frontier ahead of the trip. “We have to do what we have to do, to bring back the remains.”

dsc_9059.jpg

U Soe Win, the great grandson of King Thibaw and Queen Supayalat, at an event held in Yangon on December 8 to commemorate the centenary of Thibaw’s death. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

Soe Win admitted that in order for Thibaw’s body to be returned, permission would be required from both the Myanmar and Indian authorities.

Such a move would not only be important for him as a descendant, but for the whole country, he added.

“They did not go there by will, so we need to bring him home. The queen is buried in Yangon, but that is a temporary tomb. We have to take them together back to their original place in Mandalay, to the palace.”

Likewise, Hteik Su Phaya Gyi thinks the time is right.

“It is quite natural,” she said. “He is deserted there.”