For now it’s the domain of a few hardy pioneers, but the potential applications of 3D printing are endless – and could help to address some of Myanmar’s most pressing social issues.

By SEB HIGGINSON | FRONTIER

KO LINN Htin looks proudly over the 3D printed products – a mixture of figurines, clockwork toys and jewellery – on display inside the Life and Challenge company office in South Okkalapa. The 15 objects on the table in front of him are just a sample of his inventory: there are dozens, if not hundreds, more downstairs.

Linn Htin is the general manager of Life and Challenge, which he says is the only 3D printing company in Myanmar. While it’s difficult to verify this assertion, uptake of 3D printing in Myanmar has so far been limited. Nevertheless, a few individuals like Linn Htin see the enormous potential of the technology and hope to use it to address some of the country’s biggest challenges.

3D printing, or additive manufacturing, is a production technique through which products are created in a wide variety of materials, including paper, metals, resins and plastic. In its simplest form an object is printed from a digital file, layer by minuscule layer, and glued or heated together until a complete structure has taken shape.

Common applications of 3D printing include production of items for use in the automotive and aerospace sectors, the medical industry, and art and design fields. More exotic applications include the printing of guns and clothing. In the near future, food and other vital resources could be created with a 3D printer.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Life and Challenge employees using an Artec scanner to create a 3D file. (Seb Higginson / Frontier)

Life and Challenge is primarily an import/export company, and it was through this business that Linn Htin first became aware of 3D printing. An existing customer asked him to import one of MCore Technology’s plastic printers, and Linn Htin was immediately intrigued by the possibilities the technology offered.

Several months later, two Life and Challenge employees travelled to MCore’s base in Ireland, where they received training to operate one of the first 3D printers in Myanmar. They have since scanned, printed and imported products for a small base of customers: primarily government research facilities, but also about a dozen jewellers keen to introduce their customers to a cutting-edge form of personalised jewellery.

Despite these intermittent bursts of enthusiasm, the introduction of the technology to Myanmar has not been without its challenges. One of the immediate issues Life and Challenge faced was United States sanctions, which prevented it from importing the US-made raw materials needed to begin operations. To their good fortune, these sanctions were dropped by the end of 2012.

While one hurdle has been removed, uptake of the new technology in Myanmar has still been slow.

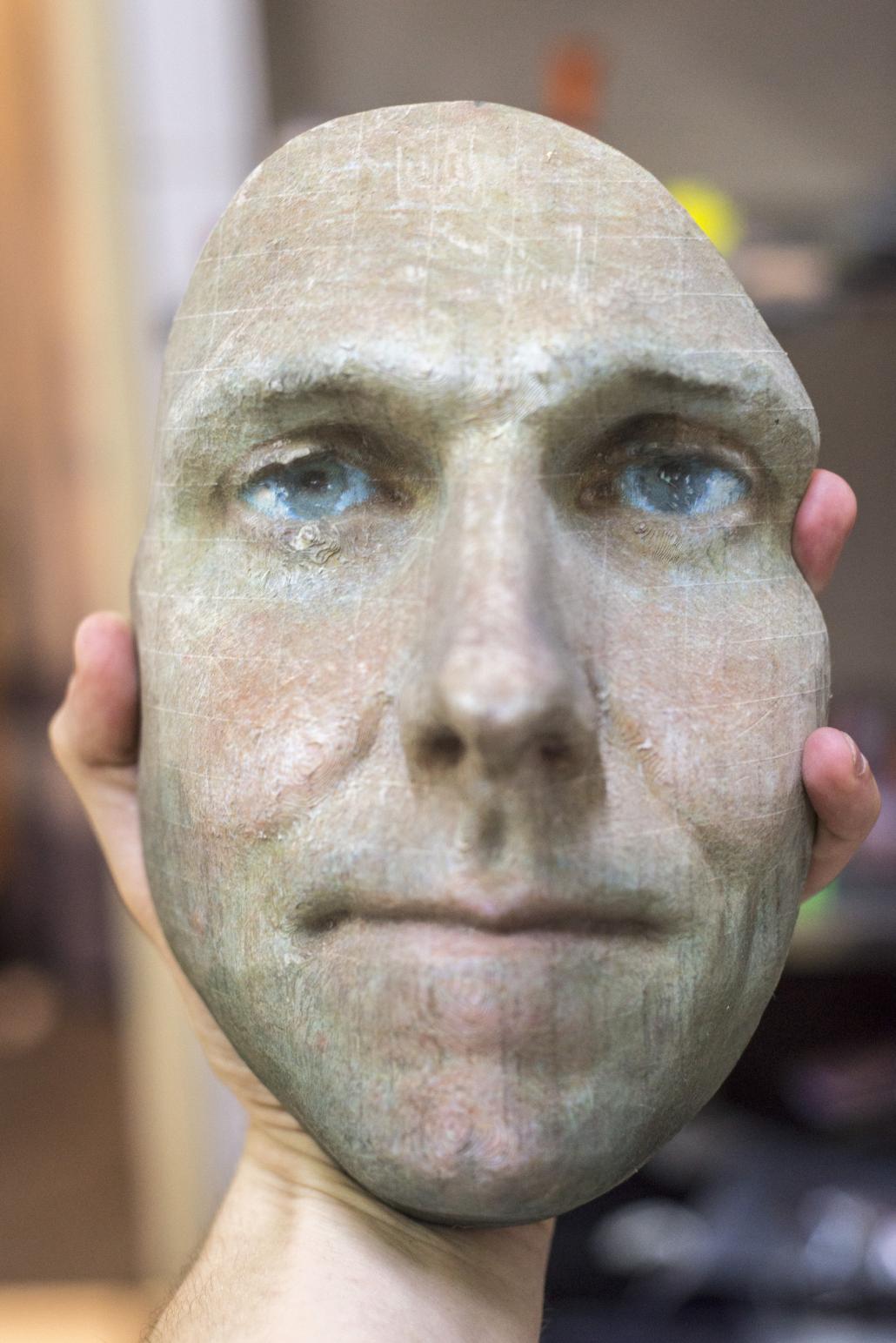

A paper replica of a human face printed by Life and Challenge. (Seb Higginson / Frontier)

“There is poor technical knowledge in Myanmar – Yangon Technology University, for example, still doesn’t own a 3D printer. Myanmar is also not industrialised, we don’t have the infrastructure to properly develop production technologies,” Linn Htin told Frontier. “And there are more fundamental problems – we have regular power cuts, and some of the printers are extremely sensitive to heat.”

These are difficulties that Ko Myat Charm, operation assistant at Yangon tech hub Phandeeyar, is all too aware of. He is responsible for the 3D printers in their Maker Space, which allows interested parties free use of the technology. Because there are so few 3D printers in Myanmar, he often has to explain the concept and process from scratch.

Myat Charm was first introduced to 3D printing in late 2015, at a Phandeeyar event sponsored by the United States government’s aid agency, USAID, titled “Hardware Hack”. USAID paid for Ko Tun Min Soe – a Los Angeles-based expatriate and industrial designer – to return to Myanmar with two printers, and he trained the Maker Space staff in their use at the event.

“I had heard of 3D printing, but never actually seen it. It’s a little bit difficult to understand it without seeing it in action,” reflected Myat Charm.

Yet once he had seen 3D printing in person, he was hooked.

“It’s incredible technology with a lot of potential. I recently discovered that you can 3D print concrete buildings – that’s amazing,” he said.

Another Hardware Hack event is in the pipeline for later this year. Now that there is a base level of 3D printing knowledge in Phandeeyar’s network, Myat Charm is hopeful that they will be able to introduce more advanced concepts and techniques. The main parties using Phandeeyar’s 3D printers at the moment are students, who Myat Charm believes will drive the technology’s uptake in Myanmar.

So what potential does 3D printing hold in Myanmar?

Presently, most in-country activities are for conceptual research or small-scale commercial projects. But there is one application that seems destined for use in many nations that, like Myanmar, have a history of armed conflict: 3D-printed replacement limbs.

A metal 3D printed hand brought to Myanmar from the US by Ko Tun Min Soe for Phandeeyar’s ‘Hardware Hack’. Metal 3D printing is more complicated than plastic or resin. (Seb Higginson / Frontier)

These have the potential to change lives. Myanmar is one of the three most dangerous countries in the world for landmines according to the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, with 3,745 casualties recorded between 1999 and 2014. However, this is thought to be just a fraction of the real number.

Despite some progress toward a peace settlement, there is no comprehensive mine-clearing agreement in place. Demining organisations that have set up in Yangon in recent years are yet to remove a single mine, and the Tatmadaw and armed groups continue to lay more.

According to the few organisations that provide prostheses in Myanmar, landmine victims account for about half of all people in the need – the rest have lost limbs as a result of accidents and disease. As Frontier recently reported, capacity to treat and provide follow-up support to those in need of prosthetics is estimated at just 10 percent of total need.

3D printing could contribute to narrowing this gap through custom-fitted, lightweight prosthetic limbs to replace those lost.

These have been trialed extensively across the world. They can give survivors of landmine accidents – and others in need of limbs – a much greater degree of mobility and autonomy than the mass-constructed and often ill-fitting plastic or wooden prostheses currently on the market.

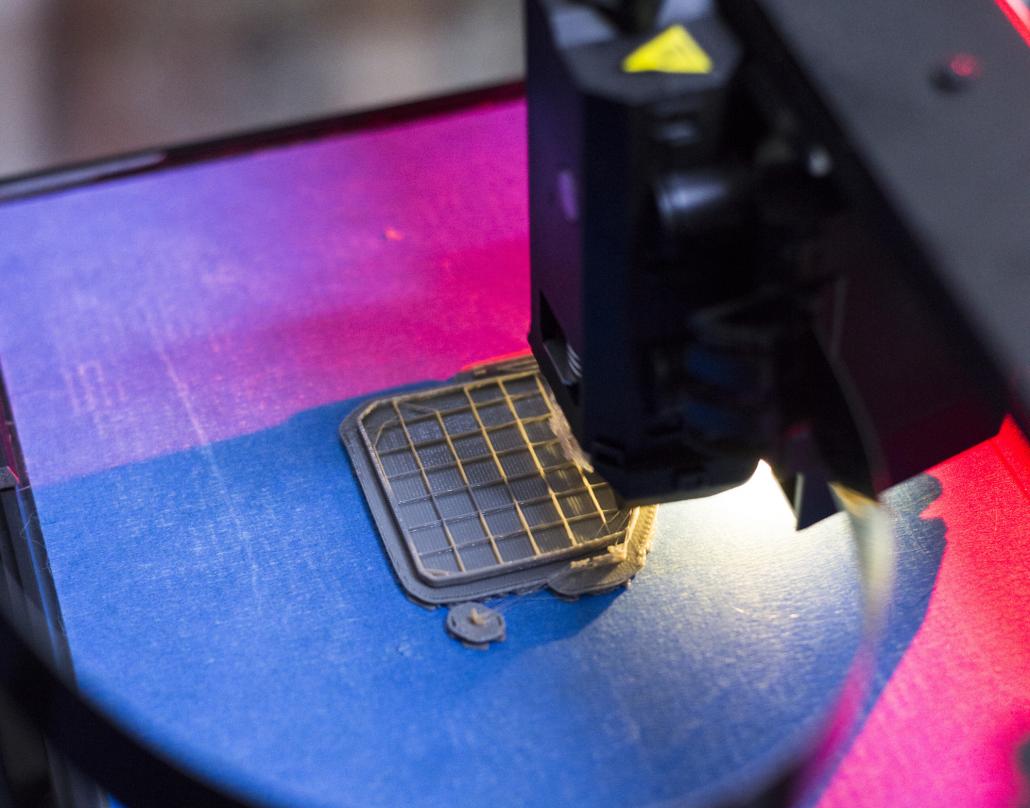

One of Life and Challenge’s plastic 3D printers in action, creating a replica of a scanned and scaled-down artist’s statue. (Seb Higginson / Frontier)

Myat Charm sees another, potentially far-reaching application: printed concrete buildings. Quick to build, strong and cheap, they could be used to create camps for those affected by disaster or conflict, or to help alleviate Yangon’s acute housing shortage.

First, though, some things need to fall into place for 3D printing to flourish – stable infrastructure, for a start. Greater education and awareness about the opportunities 3D printing affords, as well as relationships with international partners to make them happen are needed.

It remains to be seen whether Myanmar can take advantage of the opportunity and all the benefits it could bring.

This article originally appeared as part of Frontier’s Digital Myanmar 2016 special edition. Top photo: A 3D file, created from a scan, is prepared for printing. (Seb Higginson / Frontier)