More than 60 years after a plane crashed in the Kayin Hills at the end of World War Two, killing all 16 allied soldiers onboard, families of the deceased have paid their respects at a ceremony in Yangon, finally bringing some closure.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

IN JANUARY 1953, Wing Commander WR Gunn, a casualties officer from the Royal Canadian Air Force, wrote a letter to Harold Smith concerning his son, Warrant Officer 1st Class Harry Smith, who had died in the mountains of Kayin State shortly after the end of World War II.

“I am sorry indeed to have to inform you that owing to unsettled conditions in Burma, it has not been possible to recover the graves of your son and the other occupants of the aircraft.

“You are, however, assured that if, at a future time, it becomes possible to recover your son’s grave, it will be moved to a Military Cemetery where a headstone will be erected and permanent maintenance provided.”

dsc01451.jpg

Lieutenant-Colonel Sydney Wigginton, one of the 16 allied soldiers who died in the KN 584 crash. (Supplied)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Nearly 64 years later, the remains of Harry Smith and 15 others who died when Dakota KN 584 crashed on September 7, 1945, are still buried in a monastery compound in Mewaing, a remote village on the road from Bilin in Mon State to Papun, Kayin State.

Decades of fighting between the Karen National Union and the Tatmadaw – often described as one of the world’s longest-running conflicts – have so far rendered that long-promised repatriation impossible.

But for the relatives of the deceased, a closure of sorts finally arrived on November 13. As the diplomats, military attachés and schoolchildren filtered out of Yangon’s Taukkyan War Cemetery at the end of the Remembrance Day service that morning, a small group remained behind for a much more personal memorial.

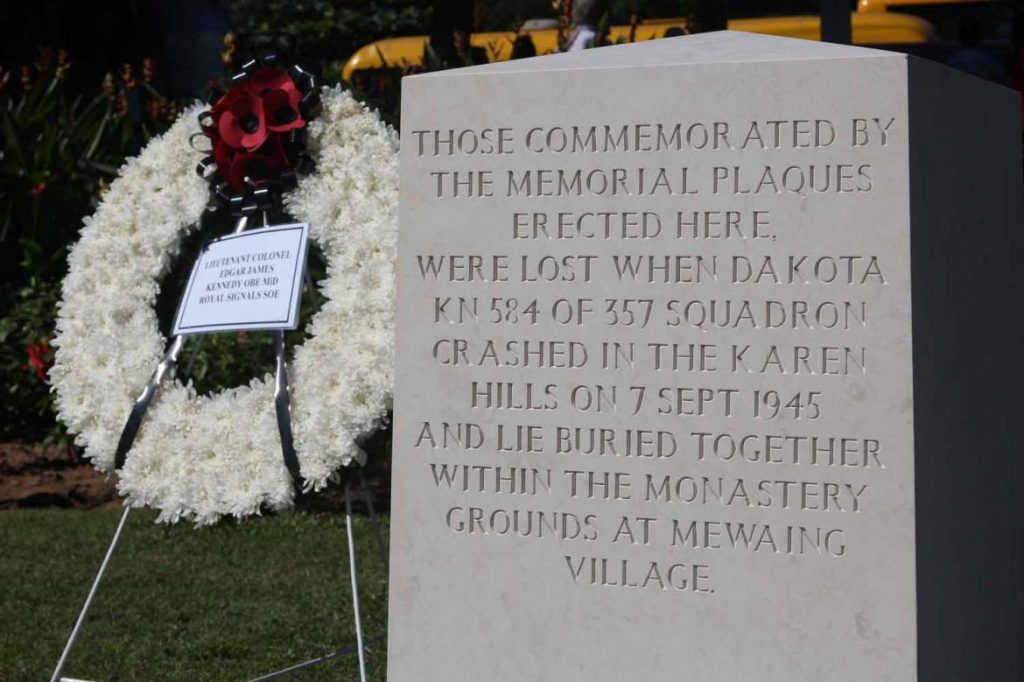

In the front right corner of the cemetery, a Commonwealth War Graves Commission banner obscured a stone block and 16 pedestals with bronze plaques commemorating those who died in the September 1945 crash. With short speeches concluded and the banner removed, relatives of four of the deceased who had travelled to Yangon for the ceremony began laying wreaths.

img_4478.jpg

Gavin Wigginton and nephew Alex Wigginton lay a wreath in front of Sydney Wigginton’s memorial plaque. (Supplied)

The last of these was Gavin Wigginton. After placing his wreath on a wooden stand above a plaque bearing Lieutenant-Colonel Sydney Wigginton’s name, he lowered his head and paused for a few seconds.

With that small but meaningful show of respect to the father he never knew, a three-year quest that had taken him from rural Victoria in Australia to the National Archives in Kew, London, and the mountains of Kayin State – the latter in spirit, if not in body – had been completed.

“I guess that was the moment at which I said, you know, I’ve done the right thing,” Wigginton later told Frontier. “You’ll be remembered now – not missing in action.”

The plaques and memorial stone would probably not exist but for Wigginton’s persistence. In 2013, he began researching his father’s life, intrigued by references to unusual wartime activity across Europe and Asia in a cache of documents left by his late mother.

A visit to the National Archives that year revealed that Sydney, who ostensibly served in the Sherwood Foresters, had in 1942 been recruited into the Special Operations Executive, an undercover organisation that conducted operations behind enemy lines. Much of his work during the war – even his citation for an Order of the British Empire – had remained classified for decades. Now it was being revealed.

A logistics specialist, Sydney was sent to work in the Southeast Asian theatre in February 1945, a time when SOE was arming and training both ethnic Kayin insurgents and General Aung San’s Anti-Fascist Organisation.

By September, Japan had surrendered and Sydney’s war was winding down. But he had one final mission to make – a debriefing of recently released prisoners of war.

When Dakota KN 584 left Rangoon’s Mingaladon airfield for Calcutta via Taungoo on September 7, Sydney was just a week away from returning home to his wife Eunice – then pregnant with Gavin – and his young son Michael.

On the way to Taungoo, the plane was due to make an airdrop at Mewaing, where SOE had been training and supplying ethnic Kayin troops to stage guerrilla attacks on the Japanese lines.

But shortly after take-off from Rangoon, the plane hit bad weather and was unable to find the drop site. It eventually crashed into the nearby hills – by many accounts, it was the last fatal air crash in the Burma theatre of World War II.

8.jpg

British Ambassador to Myanmar Andrew Patrick attends the Remembrance Day ceremony on November 13. (Thomas Kean / Frontier)

In January 1946, an officer visited the area and, together with locals, recovered what he could of the remains and buried them in the compound of Mewaing’s monastery.

Unable to visit Mewaing – which is considered a “brown area” as it is under Tatmadaw control but also has a KNU presence – Wigginton was put in contact with an ethnic Kayin woman named Naw Jercy. Together with her son, Ephraim, she travelled to the village, visited the mass grave in the monastery and met an elderly man who remembered the crash.

For decades, the 16 people onboard KN 584 had been recognised at Taukkyan on what is known as the Rangoon Memorial, which bears the names of nearly 27,000 men who died during the campaign in Burma but have no known grave.

Having confirmed that the men did in fact have a known grave, Wigginton began lobbying the CWGC, which manages Taukkyan, to consider a separate memorial. His discovery of the proceedings of an SOE inquiry into the crash, which also confirmed the burial site, strengthened his case.

CWGC spokesman Mr Peter Francis said discussions were then opened with the families and the Ministry of Defence about an “alternative” commemoration. “Essentially, those lost do have a known burial but it is not practical at present to visit or care for it,” Francis told Frontier by email.

The commission eventually decided on a special memorial, known as a “Duhallow block”, which had been introduced by the CWGC after World War I.

They have often been employed to commemorate those who had died in the conflict and were buried in a cemetery that was subsequently damaged by shellfire, but also in cases where graves could not be maintained for other reasons.

dsc01461.jpg

A cross marks the mass grave of the 16 servicemen inside the compound of the Buddhist monastery in Mewaing village, Kayin State. (Supplied)

The block, crafted at the CWGC headstone and engraving production centre in northern France, bears an inscription with details of the crash. The plaques were manufactured in Australia; from start to finish, the project took just over a year.

When Mr Christopher Whybrow learned there would be a memorial in Yangon for the victims of KN 584, he immediately made plans to attend. His uncle, Lieutenant-Colonel Edgar Kennedy, served in the SOE together with Sydney Wigginton, and also received an OBE for his secret war service.

Whybrow said he had always been interested in his uncle’s life, and had stepped up his research after retiring a few years ago.

“My earliest memory in life is of Edgar when he stayed with my parents in November 1944 during his last leave, when I was aged just over two,” he said. “In addition to this my mother adored him, he was my godfather, and regarded in the family as a real hero.”

Kennedy’s family wasn’t alone in holding him in high regard. After the crash, his commanding officer, a Colonel Cumming, wrote a letter to Kennedy’s widow praising him for tackling the undercover operations in Burma “like a lion”.

“In a short time he had reorganized everything, and in the end the operations were more of a success than any of us dared to hope. For this much of the credit is due to him,” he wrote.

Whybrow, who attended the November 13 ceremony with his nephew, described the memorial as “perfectly conceived, located and executed”, and a “fitting” tribute to his uncle.

“I cannot exaggerate how grateful I am to the CWGC,” he said. “The service provided some of the most moving moments of my life, and was a highlight of my life.”

Although the question of the memorial at Taukkyan is settled, the future of the mass grave at Mewaing is less clear. Francis from the CWGC said that even if peace does come to Kayin State, it’s unlikely the men would be repatriated to Taukkyan.

“If the site became accessible it is more likely that we would consider whether it was possible to mark the graves in situ. Exhumation and movement of remains is always a last resort as we believe the individuals should be allowed to rest in peace,” he said.

Gavin Wigginton and Christopher Whybrow expressed similar sentiments.

“My family and I think it appropriate that the bodies should remain where they have been for the last 70 years. We hope that if and when the security situation improves that the gravesite will be marked simply, and will be protected and maintained,” Whybrow said.

Wigginton said it should depend in part on local sensitivities. He noted that a number of men on KN 584 had worked among the ethnic Kayin soldiers who fought so bravely for the British.

“I think it’s a very interesting piece of the history of this country that there were all these Karen people who worked with the British officers, fighting for a cause, and they did a very fine job. The fact those people are buried [at Mewaing] is associated with all of that, so it’s part of their history.”

After all these years, does a memorial matter, though? It is clear that, for the relatives at least, it does very much – enough to draw them from Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom to Yangon for the commemoration on November 13.

“The remains of one’s ancestors do have meaning,” said Wigginton, who recently completed the first draft of a biography of his father. “They don’t really affect how you live your life today, but they provide some context for who you are, and why you are who you are, and connect you with the continuum of the life story of your family.”

“I would not have said any of those sorts of things until the past two or three years. I was brought up in an environment where we didn’t really talk about the family very much,” he said. “But having done the research on my father, I have a much better sense of who I am; I think I am my father’s son.”

It’s a reminder that, for every name inscribed on the majestic Rangoon Memorial, and every bronze plaque on the carefully tended lawns at Taukkyan, there is a unique tale of sacrifice and loss.

Top photo: The Duhallow block in Taukkyan War Cemetery sits beside plaques for the 16 Allied servicemen who died in the KN 584 crash. (Thomas Kean / Frontier)