Technological change has wrought havoc with comics in Myanmar and veteran cartoonists worry about children failing to acquire the reading habit.

By SU MYAT MON | FRONTIER

COMIC BOOKS emerged in Myanmar in the 1930s and enjoyed a golden age in the 1970s and 1980s. But in more recent times the industry has struggled, mainly because of competition from the internet, DVDs and imported publications.

There are about 10 comics regularly published in Myanmar, including Putet, Kid Zone, Happy Time and Palote Tote, but the industry is a shadow of itself as increasing numbers of children turn to IT as their main source of entertainment.

But for leading comic book publishers, their products are not only a source of fun – they also impart lessons and morality on young readers, as well as encouraging the act of reading itself.

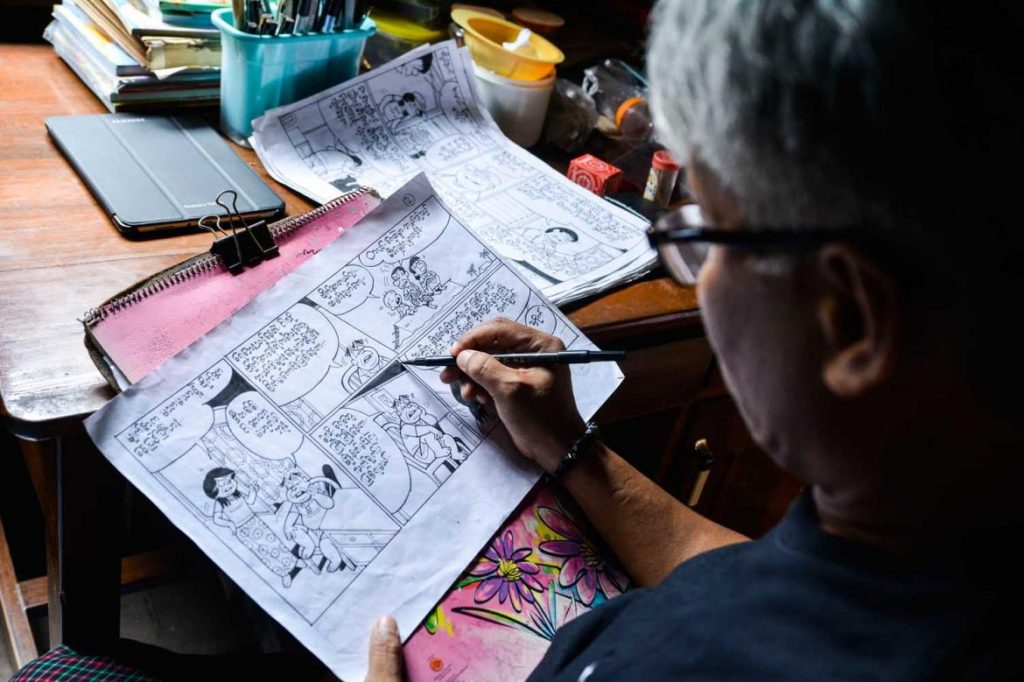

U Myint Htay, 60, better known as the cartoonist U Poe Zar, said he began drawing cartoons in 1973. He creates cartoons for Putet, which is published every Thursday.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Although cartoonists are generally paid little for their work, the declining interest in comic books still makes it difficult for the publications to earn a profit, Myint Htay told Frontier.

“The contributor’s fee is not enough to support a family,” he said.

Many cartoonists have left the industry for financial reasons and only a few well-known cartoonists earn enough to make a comfortable living, he said.

He said the declining popularity of comics is symptomatic of the effect of television and the internet on the reading habits of young people. He worries what this could mean for future generations.

“If the reading habit disappears, children will be weak in morality and artistic creation in future,” he said.

U Myint Tay, better known as the cartoonist U Poe Zar, at work in his Yangon office. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

The departure of many from the comics industry has been a constraint on creativity that has resulted in little variation among publications and has affected their appeal to young readers.

Raising the standard of comics was the responsibility of cartoonists and publishers who were passionate about the industry, Myint Htay said, adding that cartoonists and writers also needed to be better paid.

It’s a sentiment echoed by U Ye Lin Cho, 33, who creates cartoons under the name Shwe Lu.

Comic books take more time and effort than political cartoons but bring in less money, Ye Lin Cho told Frontier.

“This is why it is not easy for young cartoonists and writers to become a comic writer,” he said.

Great care was needed with the storylines in comics to ensure they did not influence children in a bad way and this was why publishers should pay more to comic writers, Ye Lin Cho said.

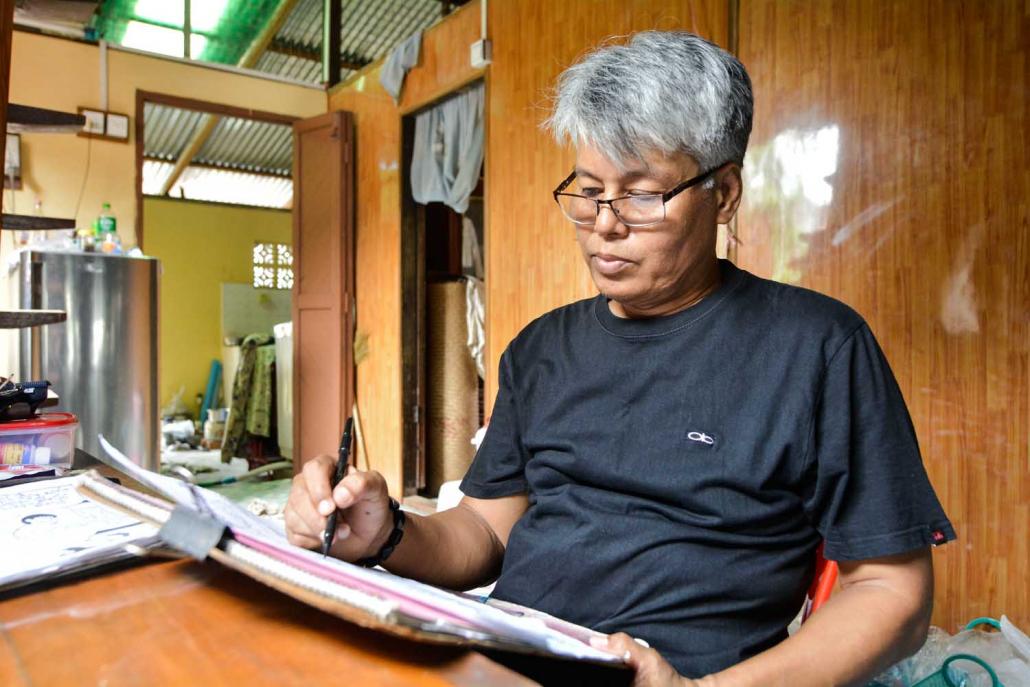

Veteran cartoonist, U Tin Aung Ne, 72, who has made a living in the comics industry since 1968, said private comics were banned in the early 1970s. After that, only state-owned comic journals were available, which over time led to a decline in quality and popularity, he said.

The government tried to use comics to push its socialist and nationalist ideology, favouring those writers willing to toe the line.

“So the situation got worse and worse because cartoonists’ ideas were controlled by government policy,” he said, laughing.

Tin Aung Ne said state-owned comics, such as Shwethwe, Moethaukpan and Tayza, were very fussy about illustration and preferred to use the work of well-known cartoonists such as U Ba Kyi, Pe Thein, U Kyaw San and U Aung Shein.

This has stifled the development of a new generation of cartoonists, he said.

“We need to promote them again in order to ensure the industry doesn’t die out completely,” he said.

“Drawing cartoons has made me happy since I started to draw as a kid and it is important for the cartoons to entertain kids and not give them bad thoughts.”

U Win Maung, 70, has published Yadanar Pankhinn literature magazine since 1966. He said the cartoon industry is facing strong competition because children were showing increasing interest in “foreign” comics, such as Superman and Spiderman, that are published locally.

U Tin Aung Ne, 72, began working as a cartoonist in 1968. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Animated movies are also easily available, and cheap at three DVDs for K1,000, but the foreign comics were expensive at about K3,000 each and not available for up to a month after publication, he said.

The cost of locally drawn comics ranges from K1,500 to K3,000 depending on the quality, with comic journals selling for just a few hundred kyat.

But Win Maung said the decline of comics was also partly the fault of the industry, as it had failed over the past 15 years to offer compelling products.

“The storylines in comics lack creativity and are boring and are losing appeal to their young audiences,” Win Maung told Frontier.

“The stories are no longer able to educate children because of the shortage of capable cartoonists,” he said.

Win Maung said the decline meant many working in the cartoon industry had changed jobs and become journalists.

Win Maung, who uses the nom de plume Maung Khit Htun, said he was having to perform the roles of writer, translator, editor and publisher of his cartoons “because all the young writers have gone to be journalists”.

He urged parents to pay more attention to ensuring that their children develop reading habits. It was an issue in which the government also needed to be involved because of the importance of reading books.

“Comics play an important role in cultivating the reading habit,” Win Maung said. “But if the illustrations do not attract the attention of children they will not be interested in them.”