The NLD reclaimed most of the seats it had won in 2015 during the weekend’s by-elections, but the threat to the party’s future mandate is clear.

From one angle, the April 1 by-election results appear to be an endorsement of the National League for Democracy’s first year in power — if not in the government’s limited achievements to date, then at least in the public’s acknowledgement of the Herculean reform challenges it continues to face.

Out of the 19 seats contested, the party won back nine of the 11 seats it claimed in its thumping 2015 victory, and would have likely picked up a 10th had party officials in Hpruso, Kayah State, been able to register their candidate before the election commission’s nomination deadline.

Yet beyond the headline figures, the weekend vote shows the rumblings of an incipient shift in Myanmar’s political landscape — one that may not pose any immediate threat to the NLD’s commanding hold over the government, but which nonetheless demands a fundamental recalibration if the party is to maintain its overwhelming public mandate.

What lessons are to be drawn from the results? First and foremost, the NLD’s loss in Chaungzon, Mon State, with a 17-point collapse in the vote, was a defeat of its own making. That the government would push through its divisive motion to name the new Bilu Kyun bridge after Bogyoke Aung San, less than two weeks before the election, suggests a lack of political judgement that borders on the absurd.

In so doing, the NLD has fortified the already widespread impression among Myanmar’s ethnic communities that celebrations of their own heritage and history will always be suborned to the cultural dominance of the country’s Bamar majority. This assessment was no doubt bolstered by numerous party figures defending the bridge decision as “unavoidable” — as if a consideration of local wishes were beyond the government’s capacity.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Party spokesman U Win Htein’s claim the NLD’s loss of Chaungzon had nothing to do with the bridge dispute, and was instead the result of a low voter turnout, does not stand up to scrutiny. Preliminary figures show the party won between 67 and 82 percent of the vote in the three seats polled that recorded a lower turnout than that in Mon State.

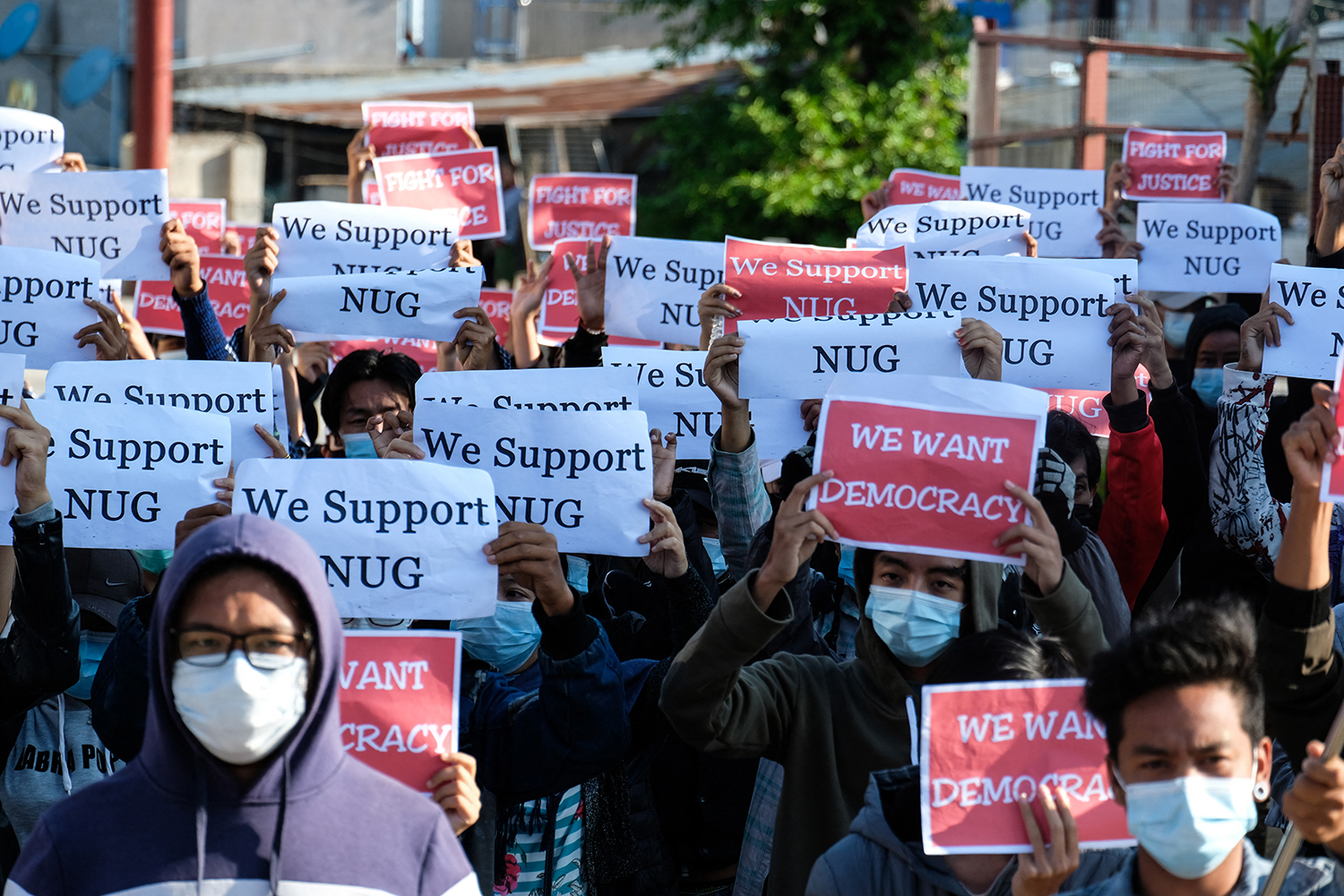

The glib dismissals of the protests that brought thousands of people onto the streets of Mawlamyine last month, and the equally facile dismissal of the real reasons for the party’s defeat, do not bode well for the party’s future chances of retaining its support in non-Bamar majority constituencies in the next general election.

The Shan Nationalities League for Democracy’s clean sweep of the six seats in Mong Hsu and Kyethi poses similarly uncomfortable truths for the governing party. In four of those seats, the party’s vote share was in the single digits; in the two Kyethi state constituencies, the NLD won less than five percent of the vote.

Here again, Win Htein has stretched the bounds of credulity by blaming the language barrier between his party’s candidates and much of the local population. Leaving aside the question of why the NLD would choose to run candidates unable to effectively represent the interests of their constituents, why then did numerous NLD candidates win election in 2015 despite not speaking the dominant language of the townships they represented?

The possibility of coercion raised elsewhere — much of these two townships are under the control of the Shan State Progressive Party — does not in itself explain the governing party’s anaemic result in these six seats. So allow us to venture a simpler explanation: the people of Mong Hsu and Kyethi don’t like being subjected to strafing runs and mortar bombardments as they were in 2015, and after a year of NLD government, no longer draw a distinction between military offensives elsewhere and the prerogatives of civilian politicians.

In any democracy, it is the moral responsibility of the governing party to represent the interests of the entire nation, and not just those of its support base. There is no bigger challenge facing Myanmar’s political transition than the need for a serious reckoning with the legitimate grievances of its non-Bamar communities, and to grapple with the reasons why, in seven decades since independence, so many have come to consider themselves outsiders in their own country.

The sooner the NLD stops dissembling and opens its ears, the sooner this monumental task can begin.