A former prison official has broken his silence on the deaths of more than 40 student activists in March 1988, six months before that year’s fateful national uprising was crushed by a military coup.

By HTUN KHAING | FRONTIER

THE SPARK that ignited the national uprising in 1988 against Ne Win’s despised socialist regime began as a dispute between students and neighbourhood youths at a teashop in Yangon’s outer Insein Township.

The students were from the nearby Rangoon Institute of Technology. They were incensed when police released one of the youths – the son of an influential local official – who had been charged with assault over the March 12 brawl.

When RIT students protested the next day, they clashed with a group of Lon Htein riot police. The security forces opened fire, killing a student, Maung Phone Maw.

Tensions quickly escalated as news of his killing by the hated Lon Htein spread throughout Yangon. There were angry student rallies at RIT and at other campuses.

000_sahk980807299630.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

A young protester is treated for gunshot wounds following nationwide anti-government protests in 1988. (AFP)

On March 16, 1988, hundreds of students at Rangoon University began marching along Pyay Road toward RIT. Their intention was to show solidarity with the RIT students. But as they were crossing a causeway on Inya Lake near General Ne Win’s residence, the road was blocked by Tatmadaw and they were savagely attacked from behind by Lon Htein.

Scores of students were killed, including some who were held under water until they drowned. So much blood was spilled that the causeway, then called Tadar Phyu, or the White Bridge, has ever since been known as Tadar Ni, the Red Bridge.

On March 18, students marched again. This time their destination was Sule Pagoda, in the heart of Yangon, but the march was again halted by the security forces. Hundreds of students and other activists were arrested.

They were herded into vans, where they were held for hours, before being sent to Insein Prison.

U Thein Win, 67, was chief jailor at the prison in 1988, the second highest position below the jail warden. Earlier this year, he published a book, Prison and Riot, about the uprising through publishing house New Idea. He had previously tried to write about 1988, he said, but the government always censored his works. His account significantly contradicts the official record put forward by the previous military regime.

Thein Win served for 16 years in the Corrections Department, but quit in 1991 after being transferred from Insein to a work camp in Sumprabum, about 200 kilometres north of the Kachin State capital Myitkyina. He said he was exiled to Sumprabum as punishment for arguing with ex-military officials who were being transferred into the department shortly after 1988.

He told Frontier in a recent interview that between 700 and 800 people, all men, were transferred to Insein in the police vans.

tzh88uprising2.jpg

Former chief jailer at Insein Prison U Thein Win. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

When the vans arrived, Thein Win said he told those in charge of the vehicles that the detainees could not be accepted because there was no arrest warrant from a judge.

“One is not taken to prison without a warrant; we said we could not accept them,” said Thein Win.

The prison officials were forced to relent after coming under pressure from their superiors. When the van doors were opened to allow the detainees to alight, they made an appalling discovery.

“There were many dead people inside the vans; it was bad,” Thein Win said, recalling that the sight of the bodies had shocked even the security personnel.

“The prisoners had been stuffed into the vehicles; they died because they didn’t have enough oxygen,” he said.

“The maximum number of people that those vans could carry was 40, but they stuffed 80 people into them.”

000_arp3513614.jpg

A demonstrator calling over a loudhailer addresses anti-government protestors on August 18, 1988. (AFP)

A government statement about the incident served only to inflame tensions. It cited an insufficient number of vans as an excuse and it indirectly blamed the deaths on anti-government demonstrations. Detainees had suffocated because detours taken by the vans to avoid the demonstrations had prolonged the journey to Insein, the statement said.

The official death toll was 41 but the list was reported to have been changed immediately before it was announced.

Thein Win said some of those who died in the vans were bystanders who had been rounded up when the demonstrations were dispersed. Among those released later was an immigration officer who did not know why he had been arrested.

Thein Win said the relationship between prison staff and the Lon Htein was tense.

“Insein at that time could accommodate only 5,000 prisoners but was holding 10,000 people and we were worried about the influx,” he said.

“We were forced to accept the prisoners and we also had many arguments about the bodies of those who died in the vans.

“The dead were not our responsibility; we were so frustrated.”

Eventually, the authorities decided to turn a garage at Insein Prison into a makeshift morgue.

Doctors were summoned to the prison to prepare medical reports on the dead and then there was a rush to cremate the bodies, Thein Win said.

They were cremated at Kyandaw cemetery in Kamaryut Township. It was then the biggest cemetery in Yangon; now it’s the site of Junction Square shopping centre.

tzh88uprising11.jpg

Photos of the 1988 demonstrations at the 88 Generation museum in Yangon’s Thingangyun Township. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

“We did not have any record of the dead people; their families must have thought they disappeared during the uprising,” said Thein Win.

The day after the cremations, something mysterious happened at Insein Prison.

The bodies unloaded from the police vans had initially been placed under a tree on the east side of Insein Prison before being processed. This tree suddenly withered and died.

Nobody can explain why the previously healthy tree died overnight, just as nobody knows who died in the vans. But Thein Win’s decision to break his silence has at least shed some new light on the atrocities committed by security forces in March 1988 – and the divisions those atrocities created among government officials.

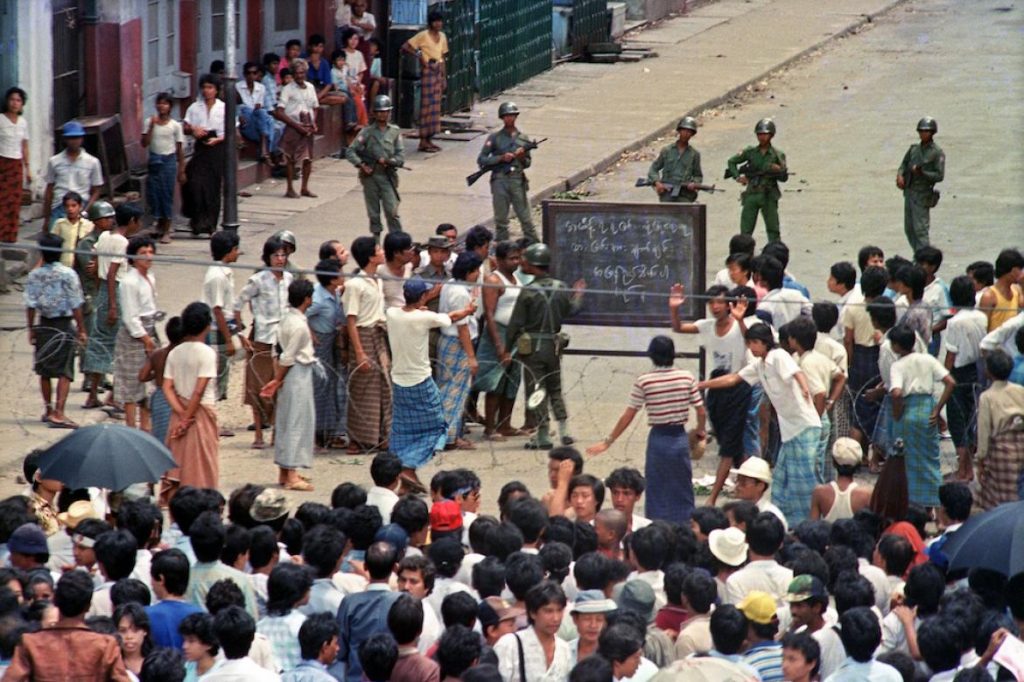

Top photo: Myanmar soldiers stand behind a barbed wire barricade as they order a crowd to disperse from in front of Yangon’s Sule Pagoda in Yangon on August 26, 1988. (Tommaso Villani / AFP)