Most journalists in Chin State are young and inexperienced but driven by a passion to bring the news to readers in one of the country’s most isolated and undeveloped areas.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

SALAI AUNG AUNG, editor-in-charge of the Chinland Post, had spent the week meeting landowners and arranging interviews with officials in the Chin State capital, Hakha.

There are plans for a five-fold expansion of Hakha’s municipal boundary, Aung Aung reported, and some farmers in the affected area have worked their land for generations but have no documents. Others have documents, but are still opposed to living within city limits.

Each of these small stories has a livelihood at stake, and the Chinland Post is one of the few newspapers that can share them with speakers of Hakha, one of the main Chin dialects.

The Chinland Post meets its duty mission to inform readers with a few office-grade printers and a handful of rookie reporters. It publishes three editions a week, which are distributed around Hakha and to any readers it can reach along the state’s rough and twisting mountain roads and trails.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

There’s little financial reward for their efforts. “We can hardly cover the cost of printing or [buying] the paper,” Aung Aung said.

Since the end of censorship in 2012, media development in one of Myanmar’s most isolated and poorest areas has been an uphill battle – often literally – as its journalists strive to inform a population of about half a million scattered throughout deep valleys and steep mountainsides.

There are now around a dozen publications in Chin State, which are published in the Hakha, Tedim and Falam dialects, as well as Mizoram and Myanmar languages. Most of their journalists are in their late teens or early twenties and have no formal journalism training, but enough passion to work for little or no money.

Despite the lacking of training, printing presses and a salary, the journalists know that if they do not report on developments in Chin State, no one will.

“Even for Myanmar, media is new. For Chin, it very, very new,” Aung Aung said. “There are many local people who cannot read Burmese, and Burmese media rarely cover Chin.”

Rookie writers

The state’s newest newspaper was founded in January by one of its oldest journalists, Dr Runbik Taithio, 69.

The Lairawn Post, published three times a week in the Falam dialect, is based in Kalay, just across the state border in Sagaing Region. But as the only paper with access to an offset press, it is able to produce its four-page editions on newsprint.

The Lairawn Post is not making money – Runbik Taithio expects it will be turning a profit within a year – and it can’t pay its reporters much more than the industry-standard of K150,000 a month.

Unfortunately, he explained, money is not the paper’s biggest problem.

“Even if we can pay them, we cannot find qualified reporters,” he said. “Most of the youth are not interested in journalism. Maybe they are educated, but they are not becoming reporters.”

Jared Downing | Frontier

The Lairawn Post fills its pages with content from staff reporters, community contributors and writing by the prolific Runbik Taithio, who spent 19 years working for a magazine in India’s Mizoram State, which shares a porous border with Chin. He returned home in 2013 founded the first Chin daily, the Falam Post, which has since closed.

Chin journalists with Runbik Taithio’s background are rare, as are those with even two or three years’ experience. Aung Aung and his executive editor, Salai Holy Tawk Tling Thang, at 27 and 30, respectively, are regarded as seasoned veterans here.

Salai C Lian, 26, editor-in-charge of the Kalay-based Chin Voice, said that even if his team had an offset printer like the Lairawn Post, they would not know how to operate it. He spends much of his time re-writing the stories submitted by his reporters.

“The journalists are very young,” C Lian said. “Many stories, like most [Chin] media, are one source only. We need basic journalism training. Feature writing. Newsroom management. Photography.”

Aung Aung has an identical wish-list for his newsroom.

“We are just learning by working, and experience is our teacher,” he said.

Organisations such as the United Nations Development Programme, BBC Media Action and the Myanmar Journalism Institute are working to provide resources and training to the journalism industry.

A big problem with the efforts to develop journalism in Chin, said C Lian, is that it is not really an industry at all.

“They do it for a hobby, or pride, or they think that if they write news, their voices will [be heard by] the people in authority,” C Lian said.

Many Chin journalists, including C Lian, are supported at least partly by the parents. Those with the most education have ambitions to become teachers or government employees, and few consider journalism as a career option.

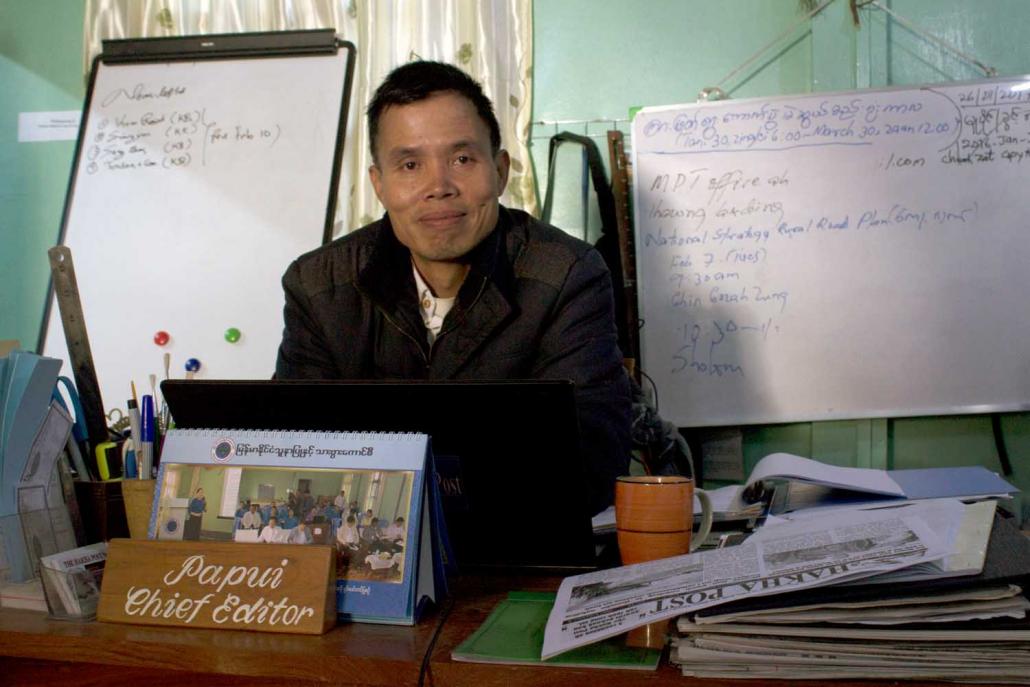

Hakha Post chief editor Salai Papui is an elder statesman of the Chin State media industry, with most reporters in their late teens or early 20s. (Jared Downing | Frontier)

Chin media still has some of its old guard, including Runbik Taithio and Salai Papui, editor of the Hakha Post.

But many have left journalism. They include Aung Aung’s Chinland Post mentor Salai Bawi Uk Thang, who is working on a master’s degree about conflict resolution in Cambodia.

“[The founders] adopted us to take over their role,” Aung Aung said. He emphasised they have not abandoned Chin State, but until they return: “What I see are very few people who have an interest in this field.”

As for himself, Aung Aung said he could not imagine leaving journalism.

“At first I was just thinking to work in [journalism] for the experience, but when I got really involved, I couldn’t get out,” he said. “Everyday I saw something people needed to know or that there was something government needed to be transparent about.”

Respect and trust

The private media publications in Chin State have not always enjoyed warm relations with the local government.

Runbik Taithio said the Falam Post was shut down in 2013 following a report in a Hakha newspaper that was alleged to be defamatory. The state’s Union Solidarity and Development Party government responded by launching a blanket crackdown on local media, he said.

Aung Aung said that in the two or three years after the first Chin newspapers appeared in 2012, the Chin government ignored the press, barring reporters from meetings of the Chin State Hluttaw and refusing to release documents in the public interest, such as the state budget.

The situation has slowly improved in recent years. In 2012, Chin publications organised into what would become the Chin Media Network, and the NLD state government that took power nearly a year ago appointed its tourism minister, Salai Isaac Khen, as an informal spokesperson.

However, the relationship between the state government and the press remains as tenuous as Chin’s narrow mountain roads.

C Lian, who is the CMN’s field coordinator, described a recent dispute over an editorial in a network-affiliated journal. It had described the attendance of a large group of state officials at a Baptist service as an inappropriate statement of religious preference within the government.

At a heated meeting, officials claimed the editorial had attacked their personal right to worship by politicising the simple act of going to church. CMN members retorted that the comment was included in an editorial, not a news report, and that the press was entitled to express an opinion.

C Lian said the fierce argument left him reluctant to attend future meetings. He would not sever ties with the government, he said, but he does believe the dispute damaged the working relationship the two sides had been trying to build.

But to Ms Allison Moore, program specialist for UNDP, the dispute was a sign of progress.

“The government understands that the disputes that come up can be resolved in a dialogue instead of immediate shutdown or de-licensing,” Moore said.

She agreed that there was an almost crippling lack of trust in Chin State between the government and the media, but said it was due to a simple lack of communication.

Officials are reluctant to develop a rapport with young, inexperienced Chin journalists because they are nervous about being misquoted or misrepresented.

Reporters have become more hesitant to approach government officials to seek interviews out of fear they will be rebuffed.

“I really believe they are reporting on what their communities are experiencing, but because they are isolated, they don’t have the channels to get the full story,” Moore explained.

Thus, the cycle of mistrust continues.

“There’s a need for this institutional change,” Moore said. “They need to understand that there’s a value in having discussions with one another.

“A lot of these early dialogues are just establishing points of contact,” she added. “It hasn’t solved everything, but there are new channels.”

Aung Aung agrees that Isaac Khen and other government ministers are making a genuine effort to communicate with the local press. However, he said 7-Day News and Myanmar Times sometimes have full access to news conferences to which the Chinland Post is not invited.

“Maybe they do not trust us because of the label ‘Chin media’,” Aung Aung said. “We are small.”

Sticking to the story

For C Lian, the Chin people can be more discouraging than uncooperative officials.

“The village people are afraid to tell the truth because they don’t want to be involved,” he said. “When we introduce ourselves as journalists, they are afraid.”

For Aung Aung, one of the most challenging parts of his job has been finding himself in the position of his own mentors, charged with leading Chinland Post’s new generation.

“Sometimes I look at what I’m doing and I think, ‘I shouldn’t be doing this,’” Aung Aung said. “But I can’t stop.”

But when he reflects on the changes of recent years, he can see that the situation for Chin media is slowly improving, one edition at a time.

“Two years ago we didn’t have any internet. … Today the government is paying a little bit more attention to what we write and the social community is more interested,” Aung Aung said. “Our voice is more powerful.”

This article was updated on March 23 with additional comments from Aung Aung. TOP PHOTO: Chinland Post editor-in-charge Salai Aung Aung reads the latest issue at the paper’s office in Hakha. (Jared Downing | Frontier)