Campaigners say that plans for a series of dams on the Thanlwin River will force the relocation of tens of thousands of people, threaten the peace process and inundate pristine environments.

By HEIN KO SOE | FRONTIER

ENVIRONMENTALISTS AND Shan, Kayin and other activists are mobilising amid moves by Myanmar, China and Thailand to accelerate controversial plans to build a series of dams on the Thanlwin (also known as the Salween), the longest remaining free-flowing river in Southeast Asia.

Opponents of the plans for the “cascade” of six big dams in Shan, Kayah and Kayin states say they will displace tens of thousands of ethnic minority villagers and complicate the peace process for the sake of generating electricity that will mainly be exported to Thailand and China.

Although in development for more than a decade, the projects have barely moved forward. However, on August 12, officials indicated that the National League for Democracy government planned to proceed with hydropower projects on the Thanlwin to help meet the country’s rising demand for energy.

A boy carries a water bucket while walking through the shallows of the Thanlwin River in Kayah State. (AFP)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The government’s need for electricity from hydro sources is acute; it has scrapped its predecessor’s plans to generate up to one-third of the nation’s power from coal by 2030, while a series of seven China-backed dams on the Ayeyarwady River are also under review.

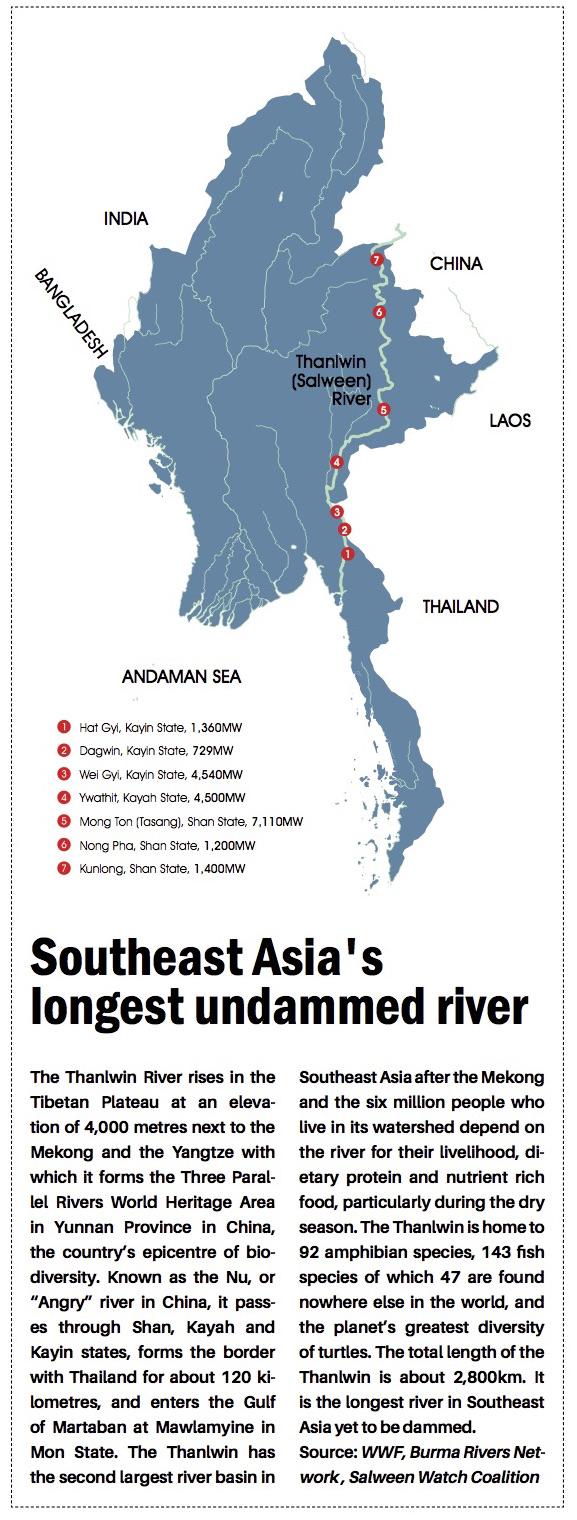

The six proposed dams on the Thanlwin will collectively deliver up to 20,000MW of power. The much-delayed 7,100 megawatt Mong Ton Dam, formerly known as the Tasang, in Shan State the largest of the six proposed dams, which also include the 4,500MW Ywathit Dam in Kayah State and the 1,360MW Hat Gyi Dam in Kayin State.

But moving forward on the Thanlwin dams will be politically difficult. Just days after the August 12 announcement, 26 Shan community groups sent an

typeof=

open letter to State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi objecting to the decision.

“Giving the green light to the dams is highly worrying,” the groups said in the August 17 joint statement. They called for an immediate halt for the projects and warned that if they went ahead they could jeopardise the peace process by increasing the risk of conflict with armed ethnic groups.

Kayin groups have blamed the Hat Gyi project for the recent fighting in Kayin between the Tatmadaw and an allied Border Guard Force and a splinter group of the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army. The clashes have displaced up to 4,000 villagers.

“If you look at the map, you can see that the army offensives are about the Hatgyi dam,” Karen News quoted Karen Rivers Watch spokesperson Naw Hsa Moo as saying on October 5.

“They’re trying to use force to clear the area so the dam can begin. We’re trying to warn people about this. If the Burmese people knew, they would not support it. But it seems like no one knows what’s really going on in Karen State,” she said.

Another Karen Rivers Watch member, Saw Thar Bo, spoke of the emotional bond that the Kayin people have with the Thanlwin.

“We don’t agree with the Hat Gyi dam and will never allow it to be built. The Thanlwin is our identity and we don’t want to destroy our identity,” Thar Bo told Frontier.

Feelings are running just as high among some Shan over the Mong Tong project and the three other proposed dams on the Thanlwin in Shan State: the 1,400MW Kunlong Dam, 1,200MW Nong Pha Dam and 200MW Mantone Dam.

In a commentary in the Shan Herald Agency for News on October 4, prominent Shan activist Sai Wansai said the issue of the Mong Ton dam “is fast becoming the Shan people’s ‘Alamo’, or last political bastion”. He warned it could lead to all-out war in the state.

Khun Htun Oo, the leader of the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, has also raised concern that proceeding with Mong Ton and the other projects in the state could threaten the peace process and national reconciliation.

“The hydropower projects in Shan State should not be implemented when there is conflict,” he told Frontier.

SNLD Pyithu Hluttaw MP Nan Khin Saw (Kunhing, Shan State) said she would use the next session of Union Parliament to call for dam projects on the Thanlwin to be scrapped.

“We need to be against the dam projects in Shan State because they threaten people’s livelihoods and it is not in the people’s interests that the power will go to other countries,” she told Frontier.

“There have been many problems with the environmental and social impact assessments of dams on the Thanlwin and the projects have not been clearly explained to affected communities, so I will ask in the next session of parliament that dam projects on the Thanlwin be rejected,” she said.

Sai Khur Hseng, from the NGO Action for Shan State Rivers, raised concern about the number of villagers who will be displaced if the Mong Ton project goes ahead. The dam will submerge an area covering about 640 square kilometres.

“The submerged area will be about the same size as Singapore,” Khur Hseng, who also acted as spokesperson for the joint statement issued by the Shan groups in August, told Frontier.

ASSR held a screening in Yangon on September 28 of a documentary it produced that shows the threat posed by the dam to thousands of villagers and to the pristine, richly biodiverse environment where the Nam Ping, a majority tributary, flows into the Thanlwin in central Shan State.

The documentary, “Drowning a Thousand Islands”, has also screened in the Shan State capital, Taunggyi, as well as Kengtung and Chiang Mai. It includes spectacular drone footage of the islands, islets and waterfalls of a largely unknown section of the Nam Pang. The river is known in Myanmar as kinhing, or kun heng, which means “thousands islands”.

The documentary also explores the likely impact of the dam on villagers facing the prospect of resettlement, a sensitive issue in the area because of the forced relocation of up to 300,000 residents of Kunhing and 11 other townships by the Tatmadaw in the 1990s.

The Thanlwin dams have been planned since at least the early 2000s. In 2006, the State Peace and Development Council junta signed a memorandum of understanding with MDX of Thailand to develop a 7,110MW dam at Mong Ton, at an estimated cost of US$6 billion.

In November 2010, just months before the handover to U Thein Sein’s government, the junta signed a new MOU with Chinese and Thai investors for the project. Its backers now include China’s Sinohydro, Three Gorges Corporation and China Southern Grid, a subsidiary of the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand, and local firm IGE, which is owned by the sons of former Minister for Industry U Aung Thaung.

But the projects struggled to get off the ground. The delays that have plagued the Mong Ton project since ground was broken in 2007 were acknowledged by Mr Areepong Bhoocha-oom, permanent secretary for energy of Thailand’s Ministry of Energy, in an interview late last month with Thai newspaper, Thansettakit.

Areepong said he was seeking a meeting with his Myanmar counterpart to move forward planning for the Mong Ton and Hat Gyi dams.

dsc_5621.jpg

Speakers at a press conference in Yangon on September 28 explain their opposition to a series of proposed hydropower dams on the Thanlwin River. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

“The 6,000-MW Mong Ton Dam has been in negotiation for a long time,” he said in the interview, cited by Ms Pianporn Deetes, Thailand and Myanmar campaigns director for the NGO, International Rivers, in a commentary published in the Bangkok Post on September 29.

“The initial agreement is that the dam will be smaller [than its previously planned 7,100 MW] and divided into two phases. The plan is to start construction in 2019. There will also be discussion to advance the Hat Gyi Dam. We expect the meeting will result in the rapid materialisation of our plans,” Areepong was cited as saying.

Planning for the Mong Ton dam has also been affected by resistance from villagers to environmental and social impact assessments being conducted for the project by an Australian company with a background in dam-building, the Snowy Mountains Engineering Corporation.

Attempts by SMEC to hold meetings and consultations with villagers had been disrupted or cancelled by protests, the Australian Associated Press newsagency reported in July last year.

dsc_5581.jpg

Steve Tickner / Frontier

In an email to AAP the following month, SMEC defended its role in the project and said it aimed to conduct “inclusive, constructive and transparent” environmental and social impact assessments that adhered to international best practice.

Frontier emailed SMEC’s Myanmar office and its headquarters in Australia to seek an update on the assessments for this report but received no reply.

Earlier this year, the company was embroiled in a corruption scandal in Sri Lanka. SMEC emails leaked to Fairfax Media in Australia suggested it had given a US$27,000 “donation” to the party of current president Maithripala Sirisena in order to secure a contract for a World Bank-funded dam project. SMEC confirmed that the money had been withdrawn in cash by its Sri Lankan office but said it was paid to a consultant.

Meanwhile, an obstacle to the Hat Gyi project, apart from community objections, is its location in one of the most heavily mined areas of Myanmar.

Survey work on the dam, in which the main investors include Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand, Sinohydro and IGE, was halted in 2004 when an EGAT employee was killed by a landmine. Work was further disrupted in 2007 when an EGAT engineer was killed by artillery fired by an unknown group.

In an event at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand in Bangkok late last month, Khur Hseng accused the NLD government of trying to implement the dams without taking into account their impact on the lives of ordinary villagers.

“While all eyes were on the Myitsone Dam, Burma has quietly sold off the Salween to China,” he said. “We fear there has been a trade-off.”

Top photo: A man carries a fishing net beside the Thanlwin River at Yaduo in Yunnan province, China, where it is known as the Nu River. (AFP)