Farmers are beginning to reap the benefits of the rapid growth in mobile phone use in Myanmar through apps that are providing them with a wealth of information.

By SING LEE | FRONTIER

KO THEIN SOE MIN was inspired to develop an app for farmers to link them to agricultural specialists after working for Relief International in Rakhine State from 2014 to 2015.

“When the farmers encountered an issue, they used to call me directly. We [NGO staff] were not always available, and sometimes we needed to contact someone else who had expertise in the solving their problem,” recalled Thein Soe Min, the co-founder and general manager of Greenovator.

The app, Green Way, which enables farmers to contact specialists and ask them questions, was launched in May 2016.

It’s not the only app that is making life easier for farmers by providing them with information to increase productivity and improve livelihoods.

promotion_southern_shan_state.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

A promotional event in southern Shan State for the Green Way app. (Supplied)

Mr Erwin Sikma, who is from the Netherlands and has lived in Myanmar since 2013, quit his job with a business consultancy and founded Impact Terra, a social enterprise that developed Golden Paddy (Shwe Thee Hnan in Myanmar), an online platform with an app, website and Facebook page, in December 2016.

Amid the explosion of mobile connectivity and upgrades to highways and other infrastructure, farmers are yet to benefit significantly from being able to access online information, Sikma told Frontier. “It is a revolution from no connectivity to full connectivity, yet there [was] no service for the farmer,” he said.

Smartphone explosion

When the telecommunications market in Myanmar opened to competition in 2014 mobile penetration was about 10 percent. It has since soared to 93 percent, says the Digital in 2017 World Overview report by social marketing firms, We Are Social and Hootsuite.

Global market research firm International Data Corporation says that in the third quarter of 2016, 80 percent of the mobile phones imported by Myanmar people were smartphones.

Although there is no known data on smartphone distribution, leaving the penetration in rural areas unknown, Thein Soe Min and Sikma say smartphone use is common among farmers who grow crops, such as paddy.

Cost is not much of an issue. Thein Soe Min says a mobile phone with limited capabilities, known as a feature phone, can cost up to K30,000, but basic smartphones costs about K40,000, making them affordable to even the low-income households.

Thein Soe Min noticed when he travelled to countries such as India, that farmers there tended to use feature phones. “Myanmar people go straight to smartphones; some farmers even find feature phones more difficult to use, like the navigation, the buttons,” he told Frontier.

Green Way has 42,000 registered users and is expected to grow to 100,000 farmers by the end of the year; it is used by farmers in 323 of the nation’s 330 townships, says Thein Soe Min.

nswks-7.jpg

Greenovator cofounder and general manager Ko Thein Soe Min shows off the company’s Green Way app. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

“When we trained farmers in the Dry Zone, 48 people in a class of 50 had a smartphone,” said Ma Yin Yin Phyu, co-founder and business development manager of Greenovator, who previously worked for the Food Security Working Group in Yangon.

Sikma says that in the areas to which his Golden Paddy team travels, such as Shan State, and Mandalay and Bago regions, nearly every farmer has a smartphone.

The information on the Golden Paddy platform is also available offline through the app, he added. The app decides which information is most relevant to the farmer’s region and crop type and then downloads it to their phone so it can be read even when there is no connection.

Despite the high penetration rate of smartphones in Myanmar, there are still communities beyond the reach of telecommunications services.

Ms Jennifer Macintyre, the communications manager for the Tat Lan Programme in Rakhine State, says some areas where it provides support are so remote and isolated they can only be reached by boat, journeys that can take six hours.

In remote areas, the use of smartphones by farmers is limited by an inadequate electricity supply and financial capability, she said.

Tat Lan is funded by the Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund (LIFT) – a multi-donor trust fund that has been working to improve the lives and prospects of the rural poor in Myanmar since 2010 and is managed by the United Nations Office for Project Services, UNOPS. Tat Lan is helping farmers in 184 communities in Rakhine by giving them access to quality seeds and teaching them scientific farming methods and financial management.

Many farmers in remote areas of Rakhine are mired in cycles of debt and cannot afford to own a smartphone.

Macintyre cited the case of a farmer who is earning K1,200,000 (about US$880) a year to support seven family members. The farmer harvests about 400 baskets of paddy weighing 21 kilograms each, that sell for K3,000. “He told us his farm feeds only his family and he depends on remittances from his older children to pay for the younger children’s education,” she said.

Macintyre said paddy farmers do not get the best price for their crop because most have to sell it immediately after the harvest to repay money they borrowed to buy seeds. “It is a matter of feeding their families,” she said.

She says apps for farming are “valuable” but access to smartphones is essential.

The weather, and more

Smartphones have the potential to provide farmers with a wealth of information, including daily crop prices, farming tutorials through online platforms, and weather forecasts.

Impact Terra is integrating satellite data from the European Space Agency and household data from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank in order to monitor the weather real-time as well as conditions affecting smallholder farmers at specific locations.

This data enables Impact Terra to know what crops farmers are likely to be growing and provide them with customised information as well as warnings about potential hazards.

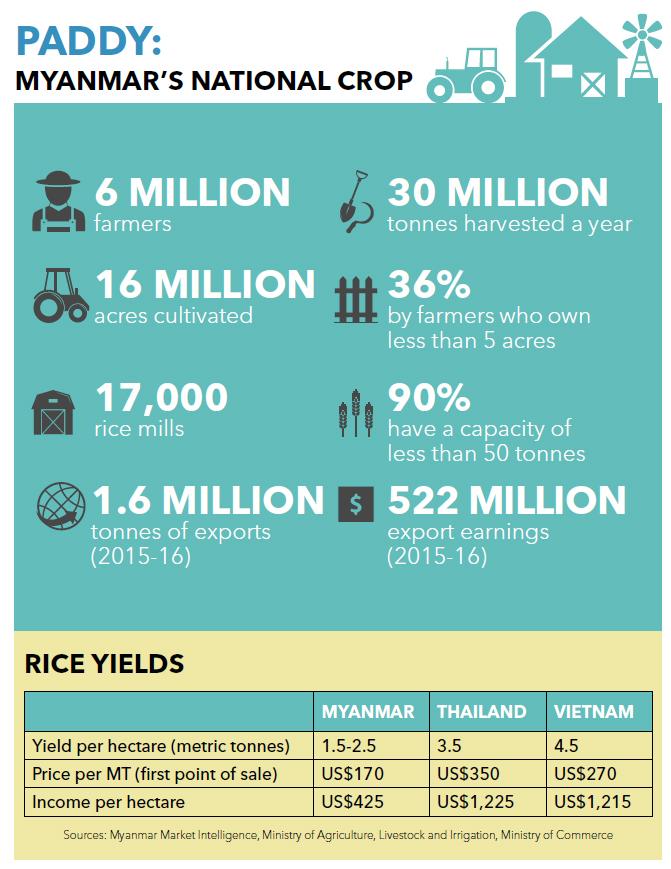

agriculture-factbox.jpg

The system enables farmers to monitor crop growth, soil moisture content, pest outbreaks and flooding. “We also rely on the feedback from our users and NGO partners; if they report a hazard, we will come up with relevant advice in the system,” Sikma said.

Thein Soe Min stressed the importance of accurate weather forecasts. He was critical of those who post fake weather forecasts on Facebook, such as warnings about storms.

“Maybe people want to make themselves famous by making fake news, but for some farmers the internet is Facebook, so it’s crucial they receive factual information,” he said.

“There is a hunger for information and they believe what they read on Facebook.”

Market access

One of the most important functions of farmer-focused apps is providing market information that helps to increase their bargaining power when they sell their crops.

Greenovator collates the market prices of more than 70 crops from 12 big wholesale centres throughout the country, and Impact Terra is working with the Department of Agriculture, whose staff input price information directly on the platform four or five times a week after visiting markets.

Impact Terra says that although Golden Paddy was launched seven months ago and is yet to accumulate enough data to be able to make a conclusion about the app’s impact on farmers, its field team is seeing changes in behaviour, especially in making sales.

“They are starting to bargain and will go to neighbouring markets to get a better price and thus have better incomes. Although it takes time to wait until the next harvest, the initial result is promising,” said Sikma.

training_for_farmers_ye_township.jpg

Farmers learn how to use the Green Way app at a training session in Ye Township, southern Mon State. (Supplied)

Thein Soe Min said that although Green Way only provides wholesale prices, it is useful information for farmers.

“If they live in very remote areas, they can still reference the price outside and estimate a reasonable transportation fee and bargain with the middlemen,” he said.

Green Way is also testing a new feature that enables farmers to input an asking price for their crop and links them with companies and traders.

“So, the buyers know where to look if they want organic chillies,” he said.

In the remote areas where Tat Lan operates, an effort is being made to increase market access for farmers.

Mr Gerasamo Pono, international agriculture manager from the International Rescue Committee, one of the NGOs implementing the Tat Lan Programme, said it is working on a pilot project that aims to eventually help farmers in 102 villages to secure better prices. The pilot is due to begin in 12 villages in October.

“The farmers do not know the price elsewhere and the buyers do not know the amount of paddy supply available at different villages,” Pono told Frontier.

He added that transport difficulties in remote areas mean that farmers have to rely on middlemen.

Tat Lan staff are able to use text messages sent by farmers to calculate the total number of baskets of paddy available at each village and exchange the numbers with price information from middlemen.

Apart from visiting each village, calls and SMS are the only way of gathering the information, as farmers with phones are only likely to have feature phones.

This is a win-win solution because buyers can save on transport by knowing which village has the type and amount of crop they want to buy, and farmers are aware of market prices, Pono said.

Education

As well helping farmers to sell their crops for better prices, information technology also offers huge potential to improve their knowledge.

Pono said many farmers lack knowledge about modern farming methods, resulting in higher production costs and lower yields.

The reasons for low yields include seeds from unreliable sources, seeds that have not been germination tested, random transplanting, the incorrect use of fertiliser (if it is used at all), and irregular weeding.

Tat Lan is working with the Department of Agriculture to provide field schools for paddy farmers, and Greenovator and Impact Terra are trying to provide knowledge through their online platforms.

As well as planning to add ethnic minority languages to their Myanmar-language services, they are also making an effort to provide agricultural tutorials that can be easily understood, regardless of the farmers’ educational background.

Greenovator, developer of the Green Way platform, also has a question and answer facility for farmers.

The questions are categorised to cover different issues, such as pests, nutrition and seeds, and farmers are advised to upload an image with their query.

“Sometimes farmers think they have a pest problem, when in fact their crop has been affected by a disease, and uploading a picture ensures they are put in contact with the appropriate expert and receive the right advice,” said Yin Yin Phyu.

The platform has about 1,000 experts in various agricultural disciplines available to answer farmers’ questions.

Thein Soe Min said Greenovator uses its connections with NGOs to verify the identity and expertise of the experts.

“I am the contact person for the Alumni Association of the Agricultural University in Myanmar, so I know some of them in person or indirectly,” he said.

He adds that any specialist can register on the platform and they all provide information voluntarily. “We offer to pay them but they do not accept because they think it is their responsibility to help farmers.”

Greenovator has a dedicated group of staff who monitor the information provided by specialists to ensure it is farmer friendly and not promoting commercial products.

“Many of our specialists are experts from foreign countries. We adopt the content to make sure, for example, that Myanmar weights and measures are used. We also get feedback from our NGO partners and directly from farmers when we visit them,” said Yin Yin Phyo.

She said that if a problem is widespread or severe, or if it cannot be identified, Greenovator will alert the Department of Agriculture.

Impact Terra is also sourcing agricultural knowledge from academic institutions and domestic and international NGOs to help farmers upgrade their knowledge through its advisory service.

Its team is making the service as simple, visually effective and interactive as possible, by minimising the use of long slabs of text and continuously improving content based on feedback from users and NGOs.

Sikma says customised information saves time because it enables farmers to go straight to the advice they need.

“You do not need to search for what you want; it is right here,” he said.

“If you grow tomatoes in Rakhine, you will not benefit from a tutorial on growing rice,” he added.

Sikma said Impact Terra encouraged farmers to make their own decisions.

“We do not believe in telling people what to do. We give them all the information available, pros and cons of different methods for comparison, and let them make their own decision. This is how we should educate,” he said.

Sikma says Impact Terra divides a tutorial into 10 sections, with the first being the simplest and smallest.

“If I tell you to write a 100-page report, that is hard. But if I say, ‘Let’s start with chapter one, that is much easier’,” Sikma said. “Farmers do not need to change their whole crop. They can start on a small scale; it may take a year or two before they see the results, but at least they are moving in a good direction, using fundamentally different approaches,” he said.

jtms-farmersapp-03.jpg

Mr Erwin Sikma quit his job with a business consultancy in Myanmar to found Impact Terra, a social enterprise that has developed the Golden Paddy application. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Macintyre says that transforming rural communities goes far beyond providing farming knowledge.

“It is mind-changing work; they only trust the people they know and trust what they see is working,” she said.

Macintyre said some remote communities benefitting from the Tat Lan project were so isolated that the advanced methods it was promoting were completely new to farmers.

Farmers will not even risk planting certified seeds until they have seen it growing in demonstration plots. They were not prepared to try a new seed variety provided after Cyclone Komen caused widespread flooding in Rakhine in mid-2015 until they saw that it was growing well after surviving 10 days under water.

“It is a matter of building long-term relationships and trust with the farmers,” Macintyre said.

Both Greenovator and Impact Terra interact with the users of their apps by regularly visiting rural areas to organise events, and visit farmers and farm product retailers. This enables them to track progress, enhance relationships and learn about user experiences first-hand.

Greenovator was launched as a social enterprise in 2011 to support organic farming and provide agricultural training for youths. It was restructured in 2015 when Greenovator was registered as a company. Green Way was launched in 2016 and is financially supported by the income Greenovator earns from consultation services, training for farmers and advertising on the app.

Greenovator also organises road shows and workshops as well as attending agricultural fairs to promote their app and keep in touch with farmers.

When this article was being researched, half of the Impact Terra team was in Shan State for roadshows to promote its platform, as well as conducting interviews to receive feedback from users.

Future plans

Sikma says helping farmers to improve their lives is challenging because of the inter-connected issues involved.

He says farmers face three main obstacles. “First, access to knowledge, to make them more informed; second, access to markets, to allow them to get better prices and buy cheaper and quality inputs; third, access to finance, such as investment and loans.

“You need to lift up the whole system for farmers,” Sikma said, adding that finance was by far the most important element, because it enabled them to enter a positive cycle and accumulate capital.

One of the most useful ways in which Impact Terra is helping farmers is by accumulating data, he said, and cited crop storage facilities as an example.

Companies or investors need to know where to build storage facilities and how to manage transport logistics. They need to know where to source crops and when they are harvested.

“We can provide this information,” he said.

Banks could also use Impact Terra’s users’ financial data and weather data to make credit assessments of farmers, Sikma said. Private banks have long been reluctant to provide loans to farmers because of the difficulty of estimating incomes and ability to meet repayments.

The data the company is accumulating is a source of revenue, as well as advertising, Sikma said, stressing that farmer users’ do not pay to access information.

Sikma emphasised that Impact Terra is not an app company, but a data research and marketing business with a profit-and-purpose model and a platform connecting all stakeholders in the agricultural sector. He says it is his ambition to make Impact Terra the Google, Facebook and Alibaba of farming.

000_hkg10226874.jpg

Impact Terra’s Golden Paddy application customises content based on where a farmer lives and what crops they grow. (AFP)

Impact Terra plans to expand its team of 15 to 50 by the end of the year and is also considering establishing a presence in Thailand and Vietnam. As a digital service it can easily be scaled up, says Sikma. The satellite data and platform structure is available and all that would be needed is translations of its services and setting up local teams, he says.

Greenovator, with six staff, is also growing, but says its focus will always be on Myanmar. It is forming a marketing team, hiring an in-house developer and planning to move to a bigger office.

Thein Soe Min has rejected invitations to work in Thailand. “Myanmar is my own country,” he said.

He says the Greenovator team derives great satisfaction from contributing towards promoting and improving the agricultural sector by making accurate, scientific information available to farmers.

Thein Soe Min recalled a telephone conversation with a teacher in Bago, who did not have a farming background.

“He successfully grew black gram on his two-hectare field using instructions provided on our app,” he said. “He was so excited when he called to tell us the news.”

TOP PHOTO: AFP