Thirteen electoral contests on November 3 won’t alter the balance of power, but will serve as a barometer of political change across Myanmar.

By BEN DUNANT | FRONTIER

FROM FREEDOMS of speech and association to government engagement with civil society, democratic trends in Myanmar appear to have beat a downward path under the National League for Democracy-led government, elected in late 2015 on the promise of building a more free society.

Meanwhile, Myanmar’s limited democratic achievements since 2015 have made for slow news copy. First among these is the holding of periodic elections, on schedule and according to broadly credible standards.

That a new round of by-elections scheduled for November 3, the second to take place under the current government, has attracted little public or media interest suggests that fair and peaceful elections are now more or less taken for granted, even if little else is.

Such complacency carries dangers in a country with wobbly political institutions, but it’s true that the by-elections won’t be much of a stress test. Just 13 seats are in play, out of 1,171 seats across the upper and lower houses of the Union parliament and the fourteen state and regional parliaments.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The balance of law-making power, now heavily tilted towards the NLD, won’t be disturbed, and no nationally prominent figures have decided to make political debuts, or comebacks, in these polls. Veteran activist U Ko Ko Gyi, whose People’s Party aims to challenge the NLD on their own reformist terms, is sitting them out; the party wasn’t registered in time to compete.

So, beyond the approximately 1 million Myanmar citizens entitled to cast ballots on November 3, should anyone else bother to pay attention? Absolutely, Frontier argues.

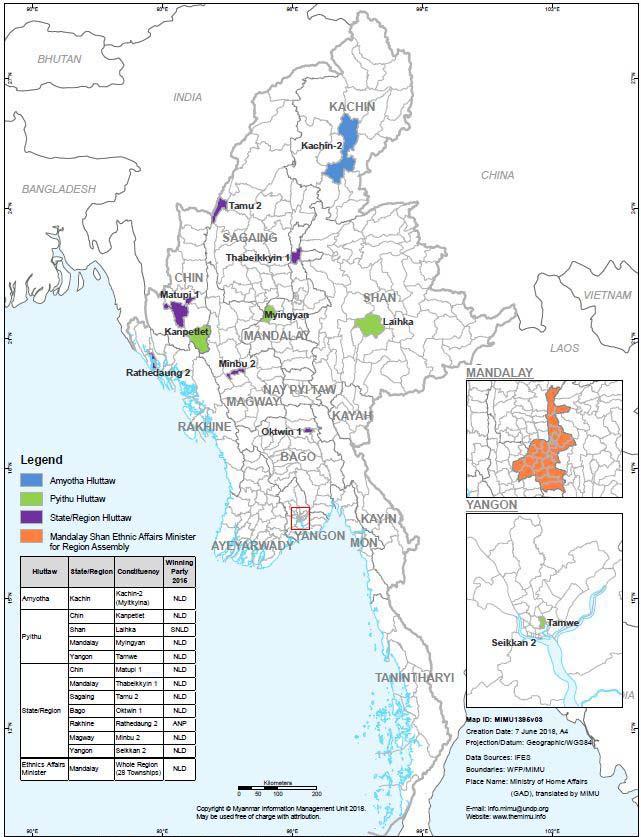

The polls will span Myanmar, with three in Mandalay Region, two in Yangon Region, two in Chin State, one each in Bago, Magway and Sagaing regions and one each in Kachin, Shan and Rakhine states. As such, they won’t just pit the NLD against its main adversary, the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party, but against an increasingly emboldened array of ethnic parties.

But, first of all, it’s worth asking: Why are the by-elections happening at all?

Because Myanmar lawmakers die with relative frequency. All but two of the seats up for election were made vacant because their occupants, elected in the 2015 general election, passed away before their terms were up.

Myanmar’s de facto system of gerontocracy – the rule of the elderly – means most aspiring politicians don’t reach high office until their 70s. Some therefore don’t hold power long before nature takes its course. In the unlikely event Myanmar elite politics suddenly pivots towards more youthful participation, expect fewer by-elections.

Second: Which are the races to watch for November 3?

In 2015, NLD candidates won 11 of the 13 seats up for grabs. The exceptions are the Rakhine State hluttaw constituency of Rathedaung-2, won by the Arakan National Party, and the Pyithu Hluttaw constituency of Laikha in Shan State.

Laikha was taken by the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy candidate with a whopping 77.8 percent of the vote. It seems fairly certain the SNLD win will again, given similar landslides in Shan in the 2017 by-elections.

typeof=

Those in ethnic Bamar-majority constituencies – Yangon, Bago, Sagaing and Mandalay regions – can be largely counted on to return solid wins for the NLD. For the Pyithu Hluttaw seat of Tarmwe Township in Yangon, for instance, the NLD candidate took 86.85 percent of the vote in 2015; for the seat of Thabeikkyin-1 in the Mandalay Region parliament, the NLD candidate took 74.46 percent.

None of the constituencies are particularly skewed by the presence of military cantonments, where soldiers and their families can be expected to vote (freely or otherwise) in large numbers for the USDP. Although Myitkyina in Kachin State hosts the Tatmadaw’s Northern Command, soldiers are greatly outnumbered by residents of the state capital.

So, in which races can we expect a real contest? Largely, those in the ethnic states.

There’s Rathedaung-2 in the Rakhine State parliament, a constituency in the north of the state. Rohingya Muslims made up a sizeable chunk of Rathedaung’s population, prior to many of them being driven from their homes in the brutal army crackdown last year. However, the large majority of Rohingya who are without citizenship were stripped of their voting rights in 2015.

The Rakhine Buddhist majority, who can vote, might be expected to return a victory for the ANP, which won 62.07 percent of the vote in 2015 and retains a platform of strident Rakhine ethno-nationalism. However, the ANP’s chances may be hobbled this time by a split in the party since the election.

The ANP was formed in the run-up to the 2015 vote by the merger of two Rakhine parties, the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party and the Arakan League for Democracy. The ANP went on to take the largest haul of seats in Rakhine, but factional squabbles since – the ALD advocating more cooperation with the NLD-led Union government – led it to break apart.

The ALD re-registered as a party last year, and will compete against the ANP in Rathedaung. This could divide Rakhine nationalist votes, handing a victory to the NLD even with a modest share of the vote under Myanmar’s first-past-the-post electoral system.

The USDP has chosen not to compete in Rathedaung – as well as in Laikha Township in Shan and Matupi Township in Chin – ostensibly to encourage ethnic parties, though this hasn’t stopped them fielding candidates in Kanpetlet Township in Chin, and in Myitkyina in Kachin.

Meanwhile, a move towards greater inter-ethnic unity, rather than division, has altered the playing field in the Amyotha Hluttaw constituency of Kachin-2, which encompasses Myitkyina. Four Kachin parties claiming the same ethnic mandate agreed in August to merge into one party. Though they weren’t able to register the new party in time for the by-elections, a candidate from the Kachin Democratic Party is running with the backing of the other parties.

A consolidation of votes could allow the KDP candidate to mount a credible challenge to the NLD, which took the seat in 2015 with 46.67 percent of the vote. However, the votes won then by the four Kachin parties put together tallied to only 30.82 percent. The KDP candidate may gain from disillusionment among Kachin with the NLD – which, in government, has stayed silent over Tatmadaw offensives in the state – but Myitkyina is one of northern Myanmar’s most diverse cities, with a large non-Kachin population.

The picture is arguably muddier in Chin. In September, three Chin ethnic parties agreed to merge into one party – again, too late to give their new vehicle a spin in the by-elections. However, for the two seats in play – Kanpetlet in the Pyithu Hluttaw and Matupi-1 in the state hluttaw – the commitment to the alliance appears uneven.

Matupi-1 is, literally, a two-horse race: only the NLD and the Chin League for Democracy have put forward candidates. The CLD is foregoing Kanpetlet, but there the other two Chin parties in the agreed merger – the Chin National Democratic Party and the Chin Progressive Party – are competing against each other.

In 2015, the NLD won Matupi-1 with 44.25 percent of the vote and Kanpetlet with 37.94 percent (just a whisker above the USDP’s 37.40 percent). In both, combined Chin party votes amounted to less than 30 percent. Allied or otherwise, Chin parties remain the underdog in the state.

However, across the by-elections, turnout will be key. Low turnouts have the potential to cause upsets even in seemingly “safe” NLD seats. In the 2017 by-elections, which involved 19 seats, only 34 percent of those eligible voted – down from 69 percent in the 2015 general election.

Since the campaign period formally began on September 3, campaign activity has overall been muted, press coverage meagre, and voter education efforts few. Victories are open to parties and candidates best able to get their supporters to show up on the day.

– Additional reporting by Hein Ko Soe

TOP PHOTO: A voter shows off the indelible ink mark he was given after casting his ballot in Yangon’s Lanmadaw Township during the 2017 by-election. (Theint Mon Soe — J | Frontier)

Correction: This article previously stated that the NLD won 12 out of the 13 constituencies where by-elections will happen. They won 11.

Correction: This article previously stated that all but one of the seats contested in the by-elections were made vacant because the incumbents died. It was all but two.