The financial authorities are investigating an online-based loan provider that was slugging customers with interest and fees totalling 15 percent a month – more than five times what microfinance institutions and pawn shops are allowed to charge.

By NAW BETTY HAN | FRONTIER

IN LATE December 2019, Ma Tin Zar received a phone call from a microlender, MicroMoney Myanmar, asking her to pay an overdue loan.

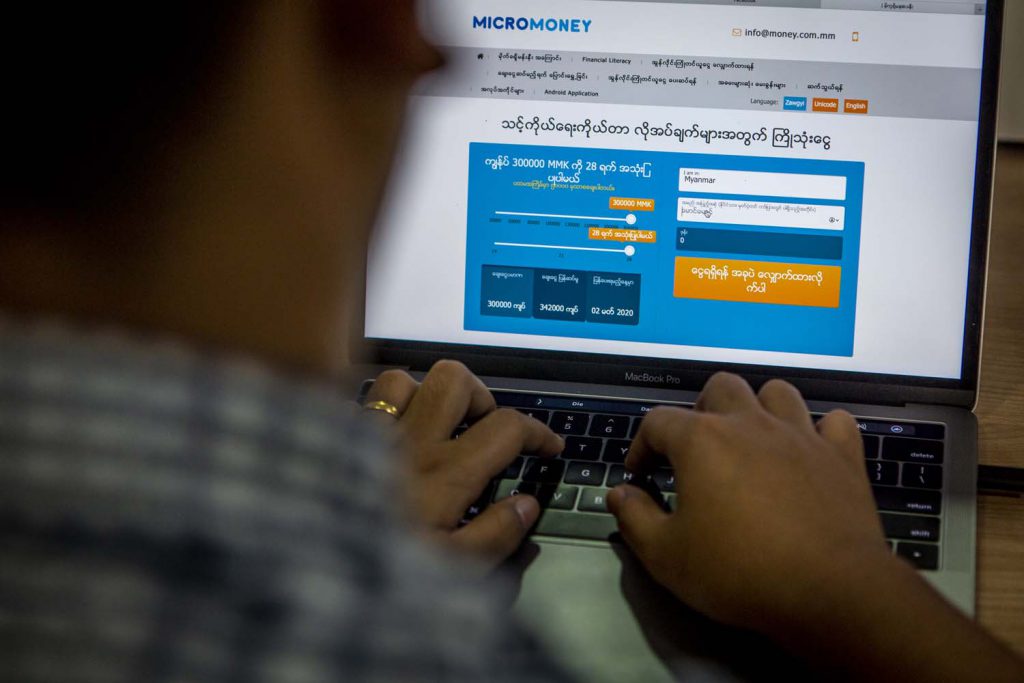

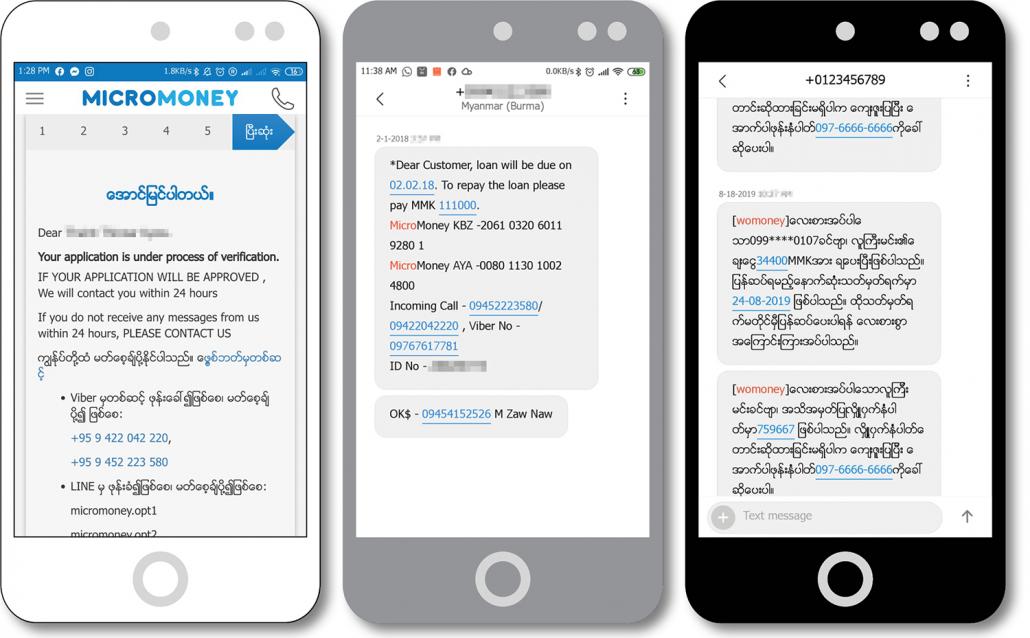

A few months earlier, a friend had referred her to MicroMoney’s mobile application through which she quickly and easily arranged a loan. The money was transferred to her through KBZ Pay within minutes.

“The interest rate was high – 15 percent a month – but I took out the loan because I was facing a financial problem and needed to borrow money quickly,” she said, showing Frontier the receipt from MicroMoney. “They only wanted to know where I worked and the phone numbers of two people I recommended.”

The loan had been due on November 12, and Tin Zar said she had forgotten to repay it. Nevertheless, she was shocked to learn how much she now owed.

On January 1, MicroMoney followed up the phone call with an email advising that she needed to repay K408,125.

How had the sum ballooned out so quickly? She had borrowed K250,000 on October 16 for a term of 28 days and was due to repay K285,000 by November 12.

But because the loan repayment was now overdue by 51 days, she was told she had to pay an extra K118,125 in interest plus an overdue fee of K5,000.

Tin Zar repaid the loan, but also deleted the MicroMoney app from her phone and resolved never to use the service again. The experience left her with lingering doubts about the legality of the service.

“The interest rate is very high and I am not sure if it is legal,” she said.

Outside the law?

Banks in Myanmar are generally limited to issuing loans at 13pc annual interest, although more recently they have been allowed to issue uncollateralised loans at 16pc interest.

Since June 2019 microfinance institutions have been allowed to charge 28pc a year, or slightly over 2pc a month. This compares favourably with the usurious rates levied by illegal money lenders, who charge at least 10 percent a month.

In contrast, MicroMoney describes itself as an “online cash advance service” focused on providing micro-loans for easy approval without collateral.

MicroMoney’s web page says it is operating its business in partnership with an unnamed pawn shop in downtown Yangon’s Botahtaung Township. Pawnshops are allowed to charge 2.5pc a month interest, and MicroMoney claims to be charging the “typical interest rate of pawnshop” plus service fees.

A chart on MicroMoney’s website reveals that while the official interest portion works out to a little over 30pc a year, the fees – for credit risk management, platform service and technical service, and credit assessment and consulting, plus a commission – are about 10 times higher, so that clients are effectively paying interest of around 30pc a month.

The chart appears to be out of date, however. At the end of 2018, the company apparently reduced its interest to 0.5pc a day, which is why Ma Tin Zar was charged around 15 percent a month on her initial loan. Frontier also tested the service in November 2019 and was charged 0.5pc per day on a seven-day, K50,000 loan.

Either way, MicroMoney’s rates are no cheaper – and perhaps higher – than most illegal moneylenders who deal in cash.

When Frontier asked the financial regulator about the company’s status, officials said it appeared to be operating illegally and they planned to investigate.

U Zaw Naing, director general of the Financial Regulatory Department at the Ministry of Planning and Finance, said he was unaware of the company because the department had not received any complaints, but that it appeared to be an “illegal online lending business”.

He said the department planned to investigate whether MicroMoney was breaching the law.

“Data from Directorate of Investment and Company Administration shows the company began operating in 2016 but we did not know about it before you started asking questions,” Zaw Naing told Frontier.

“We are looking into its business in detail and if we find out it is operating illegally we will take action under the 2011 Microfinance Law.”

Asked about the pawnshop licence, Zaw Naing said they are issued by the Yangon City Development Committee and under municipal law the pawn shop can only issue a loan if the customer gives something as collateral.

However, the MicroMoney website explicitly states that no collateral is required, and when Frontier tried the service it was able to borrow from K50,000 to K300,000 without providing any collateral.

When Frontier followed up with Zaw Naing, he said the department had been unable to contact the company and the phone number listed on its webpage was not connected.

The department had also conducted a surprise check on its registered address at Sakura Tower in downtown Yangon’s Kyauktada Township, he said, but the company had already moved.

But Zaw Naing said the department had confirmed with the Central Bank that the company did not have a microfinance licence.

The Central Bank is investigating the company, he said, and has interviewed a MicroMoney director and instructed the company to temporarily stop its business. The Central Bank has also told the department it is considering taking legal action under the Microfinance Law.

class=

A growing business

MicroMoney is not the only company that has been offering short-term loans in Myanmar through a mobile application.

Some licensed microfinance institutions, including Aeon and Mother Finance, also offer loans through an app, but the process is much more stringent than MicroMoney. Prospective customers need to upload a range of personal documents, such as a copy of their Citizenship Scrutiny Card, household list, and recommendation letters from an employer, a ward administrative officer and the township police force. They also charge interest transparently, and according to the limits set by the regulator.

But others appear to be following the MicroMoney model. In July 2019, a page named WoMoney was created on Facebook and announced that it would begin offering loans the following month. Unlike MicroMoney, WoMoney does not appear to be registered at all, even with DICA. The company claims to have an office, but does not publish its location and staff refused to give the address to Frontier.

For customers, though, the process is essentially the same. WoMoney has a mobile app available on the Google Play store. Users download the app, open an account linked to their phone number, and submit a photo of their CSC and the phone numbers of two colleagues.

Loans are limited to K40,000 per person and the term period is just seven days. WoMoney says it charges interest of K1,000 a day plus a flat K5,000 service fee. Unusually, this is deducted from the loan when it is disbursed – so the client actually receives just K28,000 and is required to repay K40,000, rather than receiving K40,000 and paying K52,000. The money is transferred to the client through Wave Money.

When Frontier tried WoMoney in October, the service was simple and fast. WoMoney called Frontier’s two referees to confirm that they worked together with the applicant. After that the money was distributed almost immediately.

In December, WoMoney temporarily stopped its service. When Frontier called the phone number on its Facebook page in January a staff member said the halt was because of an error with the application, and they were unsure when service would resume. More recently, phone calls have gone unanswered and the WoMoney Facebook page has not been updated since September 2019.

MicroMoney shifted its office to Crystal Tower in Kamaryut Township after leaving Sakura Tower in December 2018. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Who is MicroMoney?

DICA’s MyCO website shows that MicroMoney Co Ltd registered as a private company on November 25, 2016. It is listed by DICA as a foreign company with three directors: a Russian national, Anton Dziatkovskii (identified elsewhere as Anton Dzyatkovsky);Sai Hnin Aung from Myanmar; and a Japanese national, Tetsuji Nagata. The company is presently suspended because it failed to file an annual return on time, but MyCO records show it submitted the late return on February 20.

MyCO gives an office address for MicroMoney in Sakura Tower. However, when Frontier went to Sakura Tower in January it was told by the reception desk that the company had moved out of the building more than a year earlier, in December 2018.

Subsequent enquiries revealed that the company had established an office elsewhere in Yangon in Crystal Tower, near the Junction Square shopping mall, in Kamaryut Township. An LED signboard at reception in Crystal Tower says the company is in room 12A, but there is no signboard on the 12th floor to identify the office. Frontier counted more than 30 people in the office, many of whom were busy answering telephone calls about loan applications. A staff member said MicroMoney approved more than 100 loan applications a day from personal borrowers, for amounts ranging from K50,000 to K300,000.

According to its website, parent company MicroMoney Co Ltd is registered in the Seychelles, a noted tax haven. It appears to have operations across Asia and Africa, offering short-term loans through its mobile platform to clients in Cambodia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Nigeria, Cameroon and Zambia.

The company was also incorporated in Cambodia in 2016, with Cambodian tycoon Sorn Sokna listed as a member of the board of directors on several websites, including Crunchbase. Sokna, an adviser to Prime Minister Hun Sen and vice president of the Cambodian Chamber of Commerce, bears the honorific title of oknha – a rank that cost US$100,000 back when it was bestowed on Sokna in 2001 (it now requires a $500,000 donation).

Sokna was the vice-chairman of conglomerate Sokimex from 1992 to 2009, when its chairman, fellow oknha Sok Kong, was at the peak of his influence. During Sokna’s time at the company, it had a very close relationship with the government and was given many cushy deals, including a monopoly on government petroleum contracts from 1997 until 2003 and the right to sell tickets for the famous Angkor temples near Siem Reap. Its relationship with the government was criticised and the company was accused of illegal logging and skimming money from the Angkor ticket sales. Sokna now runs a company called Sonatra, which has a wide array of business interests, including microfinance.

MicroMoney says it uses blockchain – the technology that underpins Bitcoin and many other cryptocurrencies – to store the credit history of its clients and enable the fast approval of loans. In late 2017 the company conducted an initial coin offering of up to $30 million of MicroMoney coins, known as AMM, to raise money to expand its lending operations into new markets. The listing at the height of the Bitcoin craze drew significant interest and the MicroMoney coin soon hit a peak of $1.26, but quickly crashed along with most other cryptocurrencies, and for the past 18 months has traded at less than 1 cent, for a current market capitalisation of just $70,000.

MicroMoney Myanmar co-founder U Sai Hnin Aung was not present when Frontier visited the office and he later declined a written request for an interview. He said the company wanted to maintain a low profile.

However, general manager Ma July called Frontier and explained that the business was in the process of applying for the required licence from the Central Bank. She said that the approval had been delayed, and asked Frontier not to write about their company. She then offered an interest-free loan, with no documentation required.

The MicroMoney office in Crystal Tower in January. (Supplied)

‘Just for show’

One former employee of MicroMoney, who worked from October 2017 to September 2019 and was responsible for issuing loans, said the company had faced licensing issues for several years.

While the company was waiting for a microfinance institution licence, the head of the finance department secured a pawn shop licence in 2016 and “rented” his licence to the company, she said. They also used personal bank accounts in the finance manager’s name at KBZ, CB and AYA banks.

“The pawn shop is officially opened on 31st Street [in Yangon] but it is just for show,” she said.

The former employee said that by 2018 the company realised it wouldn’t be able to get a microfinance licence because of the high interest rates it was charging and lack of loan documentation.

“The company decided to continue with their business without a licence, but to be more careful than before and focus mostly on old customers,” she said.

From July to November 2018 it stopped taking new customers at all, she said. This was partly because officers from the Bureau of Special Investigations, an economic crime-fighting agency under the Ministry of Home Affairs, had been questioning MicroMoney clients about the interest rates it was charging, as well as its process of disbursing loans.

That was when the company moved to Crystal Tower. Once it restarted, the bank accounts used to transfer money to customers were now in the company’s name, she said.

Since April 2019, the company’s Facebook page – once updated almost daily with customer testimonials – has been quiet.

Despite the Central Bank’s apparent instruction to halt operations, MicroMoney is still operating. When Frontier called the company on February 24, it was told MicroMoney is once again focusing on its existing client base and had “temporarily” stopped accepting new customers.

One of the company’s existing customers, Ma Myat Mon, 42, said she supported the government taking legal action against the company. While MicroMoney was convenient to use, she described its lending practices as predatory and designed to take advantage of poor people, particularly those who are already in debt.

“I’ve taken at least 10 times from MicroMoney – if I call them, I can get a loan within an hour, it’s so easy,” she said. “But I usually use the money just to pay off other loans. Most of the other customers will be like me – they are trapped in a cycle of debt, using one loan to pay off another.

“If the government can force them to offer a fair interest rate, that would be great. If not, then it should force them to stop their business.”