A visit to the Arakan Army “temporary” headquarters in the stronghold of the Kachin Independence Army reveals a large number of fresh recruits and newly minted officers ready to be dispatched to Myanmar’s latest conflict zone.

By YE MON | FRONTIER

AS WE passed through the entrance gate into the Arakan Army compound, the two uniformed soldiers on sentry duty stood to attention, raising their rifles in acknowledgement.

I looked again. Women soldiers?

I’ve covered ethnic conflict and politics for almost a decade as a journalist and as a result visited several armed group headquarters. Most of them have women in their armies, but they normally fill administrative positions.

Not in the AA, it seems. After entering the compound, we arrived at the parade ground where about 150 soldiers of both sexes were performing drills on a parade ground. “Thanmanee seit dat!” (iron spirit!) the soldiers shouted repeatedly, as an officer stood in front of them impassively.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The camp is about 2 miles (3 kilometres) from Laiza, a remote town in Kachin State on the border with China about 100 kilometres by road south of Myitkyina. The men and women marching on the parade ground were far from their ancestral home on the other side of the country.

They are Rakhine who have joined the AA to support its struggle for self-determination in the troubled coastal state, one of the nation’s poorest and least developed.

The AA has been based in Laiza, the headquarters of its Northern Alliance partner, the Kachin Independence Army, since it was formed in 2009 to wage war against the Tatmadaw in a conflict that has escalated sharply since late last year.

Frontier travelled to the AA’s base in Laiza last month to interview its deputy chief, Brigadier-General Nyo Tun Aung, about the conflict in Rakhine, and the group’s political and military goals. There was no sign of the AA’s commander-in-chief, Major-General Tun Myat Naing, although he was apparently in Laiza at the time. AA officers said he lives in the town but does not come to the base every day.

The Myanmar government, Tatmadaw and the media describe the Laiza base as the AA’s “headquarters”, but Nyo Tun Aung dislikes the term. For him, Laiza is only a temporary base of operations until a permanent headquarters is established in Rakhine.

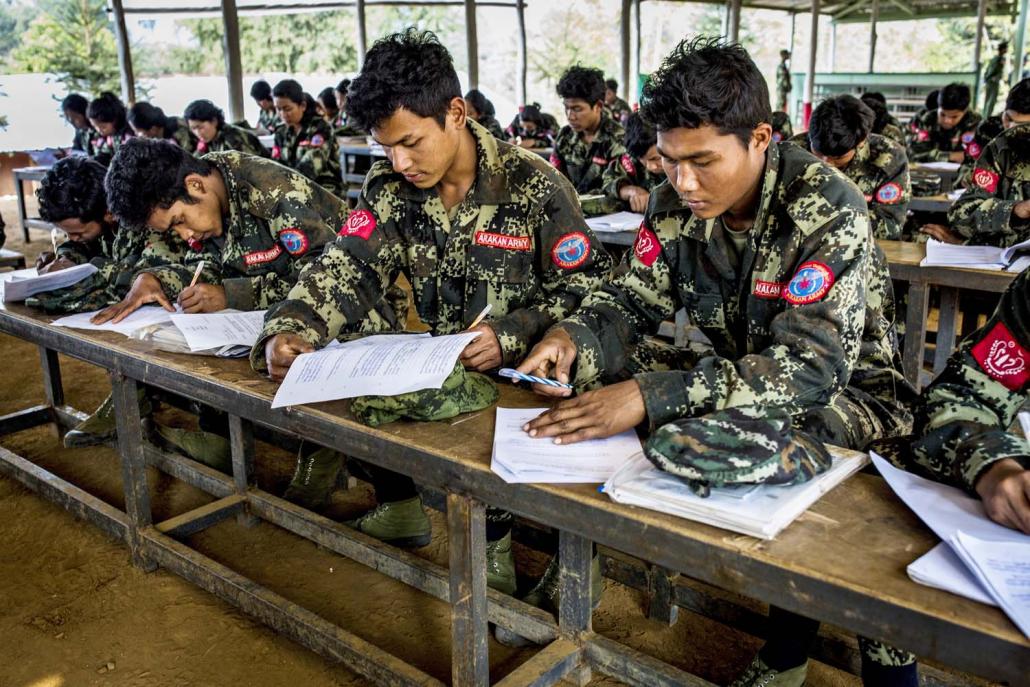

Arakan Army soldiers sit exams at the end of a three month advanced combat and platoon commander training programme in Laiza. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

When Frontier visited on March 9, Nyo Tun Aung was playing the role of invigilator while a group of around 100 officers sat exams. Over the past three months the officers had been attending a combined advanced combat and platoon commander training course. Nyo Tun Aung said the AA would complete seven batches of the training programme in March alone, at its Laiza base and other locations that he refused to specify.

Nyo Tun Aung said the AA needs to train more officers because of an increase in the number of volunteers from Rakhine State joining the group as fighting spreads throughout northern and central Rakhine.

The surge in recruits and the increased fighting since January has prompted the Arakan Army to conduct shorter courses for platoon commanders and also relax the entrance requirements.

Previously AA soldiers needed to have served for a year before they could train as a platoon commander, but now they only need three months’ experience. The training was also previously longer, running for at least six months and up to one year.

“Our army is much stronger than before and we cannot take so long to train senior officers because we have launched a revolution,” Nyo Tun Aung said, referring to the AA attacks on four police stations on January 4 that left 13 officers dead.

The officers sat their exam under a banner across a wall that declared: “Defenders of our Fatherland”. The hall was also decorated with the AA’s blue and red flag, which depicts a red star, an osprey and two golden orchids known as tiger-lady (Bulbophyllum auricomum).

The blue symbolises peace and represents the Rakhine Yoma and the sea, the red is the majesty and patriotism of the Rakhine people, and the osprey is featured because it is found throughout Rakhine State.

“The Kachin call their state a motherland and others describe their states or countries as a motherland but we call our state a fatherland,” said Nyo Tun Aung. “We need to defend our fatherland.”

There are about 1,000 soldiers at the AA’s “temporary headquarters”, including women, and some troops are based in the mountains around Laiza for security reasons. The AA needed to help the KIA protect Laiza because the KIA had allowed the AA to form and grow on its territory, Nyo Tun Aung said.

“It’s possible for you to speak with me here because the Bamar military has suspended operations [near Laiza],” he told Frontier, referring to a unilateral ceasefire the Tatmadaw announced on December 21, 2018, covering Kachin and Shan states. “Otherwise, you could not sit here because of the danger of artillery fire.”

Hkun Lat | Frontier

Nyo Tun Aung became irritated when I asked why the AA had been involved in fighting in Paletwa Township, in Chin State on the border with Rakhine.

The Arakan Army and some Rakhine people argue that Paletwa Township was historically part of Rakhine, a claim that has angered Chin people.

“I just see it as a fighting zone; I don’t see it as Paletwa,” Nyo Tun Aung said. “At this time, we don’t want to talk about that Paletwa issue. Everyone knows [that Rakhine people] live there. It would be clear if they checked the history.”

When I arrived at the camp I had been told I was not allowed to speak to any of the soldiers. At one point, while Nyo Tun Aung was overseeing the exams, I was allowed to explore the camp. I tried to strike up a conversation with some soldiers, but they ignored all of my questions. I couldn’t work out if this was because they were afraid or were just following orders.

I wanted to ask them where they came from, why they joined the AA, and how long they had been at the camp. What did they think about being sent to fight in Rakhine State? Were they afraid? Excited?

Without the chance to interview ordinary soldiers, it was difficult to verify Nyo Tun Aung’s claims that the AA’s popularity is rising and the group is being overwhelmed with new recruits eager to join the fight against the Tatmadaw.

Nevertheless, it seemed clear from my visit to the camp that the AA is becoming more powerful. Far from the front lines in Rakhine State, the AA had more than 1,000 recent, heavily armed and trained recruits ready to be deployed in the fight for self-determination.