Arguments in favour of the grand plan to build one of the region’s largest industrial zones at Dawei are deeply flawed, and vastly outweighed by its potential to damage the environment and disrupt communities.

By DANNY MARKS & TAMMY CHOU | FRONTIER

THE Dawei Special Economic Zone was jointly announced with much fanfare by the Myanmar and Thai governments in 2008 and, at about 250 square kilometres, would be one of the largest industrial complexes in Southeast Asia if completed.

However, the project has shown minimal progress: of Myanmar’s three SEZs, it was conceived first, but is the least developed. The project has been hampered by its inability to attract enough investment and strong civil society opposition. In the past four years, there has been little if any progress on the ground.

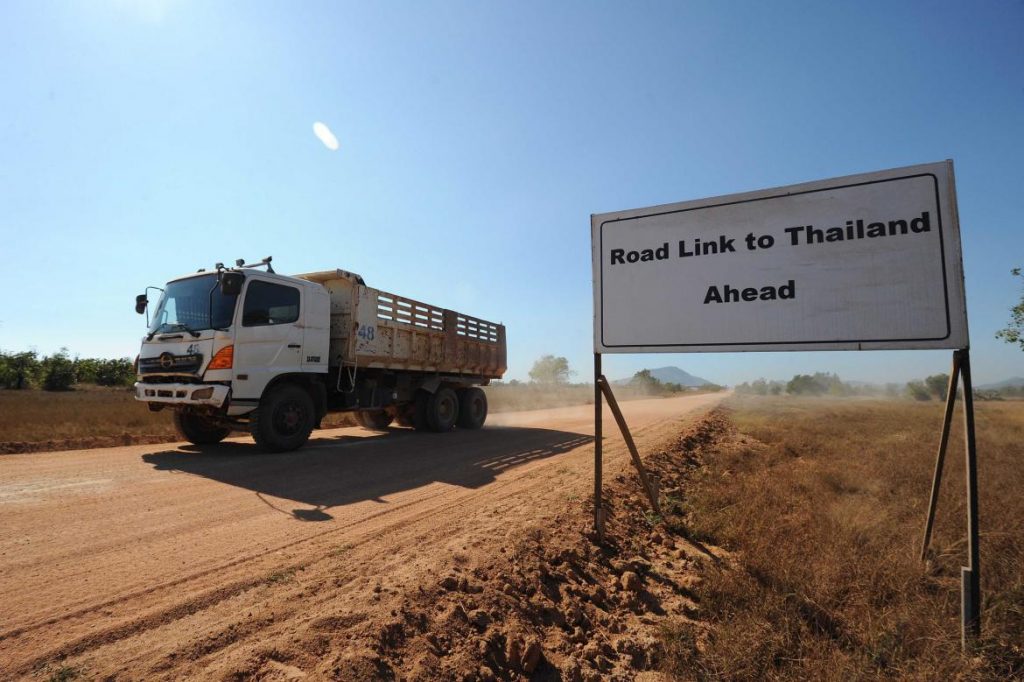

Recent signs indicate that this could be changing. In June, Thailand and Myanmar finalised a US$133 million loan to build a 132-kilometre, two-lane road linking Dawei with the Thai border town of Phu Nam Ron, in Kanchanaburi Province. In another hopeful sign, the Myanmar Ministry of Commerce said last month that it was trying to speed up work on the SEZ.

There remains a high degree of uncertainty about the project, but if it moves forward a number of environmental and social risks could emerge. They include the potential for further land grabbing, the loss of fisheries, pollution, damage to biodiversity, strain on the existing water supply, and adverse effects on human health. During the limited development that occurred under the project’s first phase, civil society groups reported cases of land grabbing and inadequate compensation.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

As the New York Times reported in November 2010, the Dawei project was seen by Thailand as a cheap and convenient solution to export is dirty industries across the border.

“Some industries are not suitable to be located in Thailand,” the report quoted then prime minister Mr Abhisit Vejjajiva as saying in a weekly television address. “This is why they decided to set up there [in Dawei],” he said.

Abhisit’s comments followed negative publicity in Thailand of the Map Tha Phut Industrial Estate on its eastern seaboard, over water and soil contamination and a heightened risk of cancer among nearby residents.

The National League for Democracy government and the Environmental Conservation Department of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation have admirably pledged that the Dawei project will be environmentally and socially responsible. However, ECD has also admitted that it does not have the capacity to monitor the project’s implementation. The department’s office in Dawei has few staff, insufficient equipment and inadequate financial resources.

The project’s primary developer, Italian-Thai Development – one of Thailand’s biggest conglomerates – has also been under fire recently over safety standards. It was reported in early May that the Japanese government’s overseas aid organisation, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, was considering blacklisting ITD over its safety record. The reports came days after three ITD workers were crushed to death while working on a project to extend Bangkok’s skytrain network that has received financial support from JICA.

Perhaps it would be better if the Dawei project was not built. Since there has been little building work so far, the opportunity cost of cancelling the project is not high. Although the government’s inability to effectively monitor whether safeguards are in place is one reason for scrapping the project, there are others.

Backers of the Dawei SEZ have repeatedly offered three arguments in favour of the project. They are job creation, the boost it would provide to the national economy, and regional integration.

However, the first two arguments were rejected by an adviser to the NLD, who declined to be named. Unlike China, the adviser said, the rural workforce in Myanmar, and particularly at Dawei, is not big enough to benefit from job opportunities at the SEZ. There was a prospect that Myanmar workers in Thailand would return to find jobs at Dawei, but this was far from certain, especially if wages in the SEZ were less than those available across the border.

The adviser said the second argument is weak because of the distance from Dawei to Myanmar’s population centres, particularly Yangon. There’s also the fact that the infrastructure connecting Dawei with the rest of the country is poor. Without better connections the SEZ could become an enclave that was not well integrated with the national economy. From a cost-benefit perspective based on these arguments, the SEZ would be of no great benefit to Myanmar; rather, it would largely benefit Thailand.

A fisherman looks out from his house near a deep sea port project near the Dawei SEZ. (AFP)

Additionally, building the SEZ would be a high opportunity cost because of Dawei’s potential for tourism. This opportunity would likely be lost if the SEZ was built. In Thailand, Phuket is a successful example of a province with a thriving economy where residents have resisted heavy industries and instead focused on tourism and service industries. Considering Dawei’s tourism potential, it might be wise to follow the example set by Phuket.

There is also opposition to the SEZ from residents of Tanintharyi Region, of which Dawei is the capital. They believe that the region already has a strong economy – it is one of the richest regions in Myanmar – and is endowed with abundant natural resources.

“I think the investment will only benefit the investors; there’s no benefit for the local community,” Sayadaw Pin Nyar Wuntha, the head monk in a village on the site of a proposed hydropower dam for the SEZ, told Channel NewsAsia in May.

“Dawei is like a zombie; it keeps coming back,” said the NLD adviser.

Considering the low level of benefits the project would create for communities, the region, and the nation, and the potential for environmental and social risks, perhaps it is time to finally put this zombie to rest for good.

The authors are members of the Urban Climate Resilience in Southeast Asia (UCRSEA) Partnership.