As the date nears for announcing a new minimum daily wage, labour unions say higher living costs support their argument for an increase that economists say could be counterproductive.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

A UNION-LEVEL panel has begun considering proposals to adjust the minimum daily wage of K3,600, which took effect in September 2015 under the Minimum Wage Law passed by parliament two years earlier.

The law requires a new minimum daily wage to be set every two years, and trade unions and workers have been pushing hard for an increase which they say is necessary to cover rises in the cost of living.

There have been a series of worker protests in industrial areas of Yangon since last year in support of an increase, which is being opposed by employers.

A cost of living survey conducted by the Confederation of Trade Unions of Myanmar in six states and regions two months ago shows that the minimum daily wage should be increased to K6,660, or K198,000 a month.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Workers at a garment factory in Hlaing Tharyar Industrial Zone, on the western outskirts of Yangon. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

The figure is based on the lowest possible living costs and does not include medical or education expenses, said Ma Khaing Zar Aung, an executive member of the CTUM and a labour representative on the National Minimum Wage Committee.

After the last meeting of the NMWC early this month, Minister of Labour, Immigration and Population U Thein Swe – who leads the committee – told journalists the possible range for the new wage was between K4,000 and K4,800.

Once the 27-member committee – which includes five employer representatives, five worker representatives, five independent experts and 12 government officials – has proposed a minimum wage, there will be a 60-day window for objections. If none are received the new rate will be submitted to parliament for approval.

The minimum wage is for an eight-hour day and is also used to calculate overtime. The first minimum wage was approved by the government and the change in procedure to parliamentary approval has been welcomed by labour groups as being more democratic.

Making ends meet

Khaing Zar Aung began working at garment factories in the early 2000s, when she was 16. Over the next five years she rose from an ordinary worker to a line supervisor, but was still earning under K15,000 a month.

Like so many before her, she decided to find work in Thailand. In 2006, she went to the border town of Mae Sot. She soon found work in a factory and was paid a basic salary equivalent to K200,000 a month.

“There was just a stream dividing [Thailand from Myanmar], but the salary was so high. And the living cost in Thailand was less than Myanmar,” she said.

That year, she also joined the Federation of Trade Unions – Burma, which had been established by activists in 1991. Trade unionism was banned under military rule and the group worked to support Myanmar workers in Thailand.

Khaing Zar Aung returned to Myanmar in 2012, after the U Thein Sein government permitted labour organisations and welcomed back exile political groups like the FTU-B. The group later changed its name to the Confederation of Trade Unions Myanmar.

She recalls that when the minimum wage was introduced in 2015, some employers responded by cutting allowances, monthly and annual bonuses, and other benefits, such as free transport.

She’s concerned about how employers might respond this time, once the new rate is approved. Nevertheless, she says the lowest amount workers need for a decent living is K6,600.

“If we cannot get that amount, the situation of workers will stay the same,” she said. “Merely surviving amid increased prices and living costs.”

Confederation of Trade Unions Myanmar executive member Ma Khaing Zar Aung, centre, speaks to labour leaders during a seminar in Hlaing Tharyar on October 28 aimed at improving relations between employers and workers. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Ma Pyae Pyae, 19, moved from Pakokku Township in Magway Region to Yangon in 2014 and works at a garment factory in Hlaing Tharyar Township.

Pyae Pyae started on K3,600 a day but after three months’ probation her salary was increased to K3,800, giving her a monthly income of K108,000. On top of this she earns about K20,000 a month in overtime but it’s still a struggle to make ends meet, she said.

“I cannot save money because I have tospend all I earn on household expenses; I would like to undertake further studies to improve my life but I don’t have the time or the money,” she told Frontier.

The macroeconomic picture

But some argue that living costs should not be the only consideration. NMWC member Dr Zaw Oo said the macroeconomic picture needed to be taken into account.

“Foreign investors always regard a minimum wage as an indicator to whether they should get into a country or not,” said Zaw Oo, from the Yangon-based Centre for Economic and Social Development, a think tank.

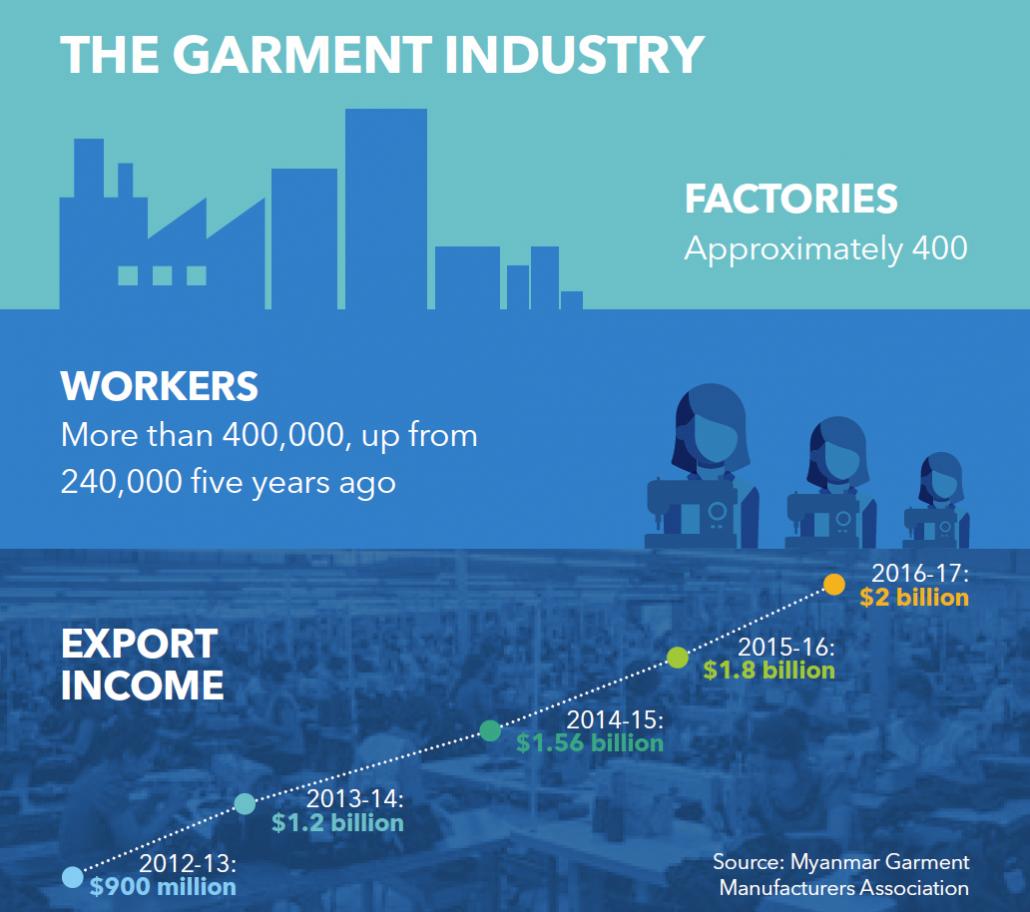

He cited as an example the garment sector, in which Myanmar’s main regional competitors are Cambodia and Bangladesh, where the minimum monthly wages are US$160 and $90, respectively. Based on an eight-hour day and a six-day week, the minimum monthly wage in Myanmar is K83,160, or about $61 at current exchange rates.

Myanmar’s garment industry in pictures.

Government figures show the garment industry is one of few economic sectors enjoying strong growth. Exports are worth more than $2 billion a year, up from about $800 million two years ago.

“If we set a high rate then potential foreign investors could move to another country,” Zaw Oo said.

Local business owners are also concerned about a sharp increase in the minimum wage. For a business with 3,000 employers, an increase of K500 would mean having to pay an extra K1.5 million a day, or K45 million a month.

Asked about the minimum wage issue, U Myint Soe, a garment factory owner and chairman of the Myanmar Garment Manufacturers Association, joked, “Tell them I can give K10,000 per day!”

Behind the humour, there are real worries about how the minimum wage will be set.

“We can’t calculate the minimum wage based on how much prices have risen,” he said. “It needs to be an amount that all business owners in this country can afford.”

Dr Khin Maung Nyo, an economist, said he believed it was not the right time for a big rise in the minimum wage.

“The [workers] will ask the rate they want, but they can only get what the employers are able to give,” he said.

Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population permanent secretary U Myo Aung cautioned that if the increase was too high, some enterprises could shut down.

“This is a very fragile issue and needs to be handled gently,” he said. “If the rate is not affordable for businesspeople, they could shut down the factories or make labour reductions. If that happens the jobless rate will rise,” he said.

But there appears to be political support for a significant increase. At an event in September, Yangon Region Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein said he favoured a minimum wage of at least K5,000.

Improving efficiency

Wages are just one factor that affects business costs, however. Efficiency and productivity – particularly the availability of skilled labour – play an important role.

Myint Soe said foreign investors placed a higher priority on skills than wages. “Even if you offered to work for them for free, if you are still unskilled they won’t give you a job.”

He urged Myanmar business owners to increase their focus on upgrading workers’ skills, and also to recognise better-skilled workers by paying them higher wages.

“Workers need to work harder and learn more enthusiastically. And employers should also manage well and not hesitate to pay more the good and skillful workers,” Myint Soe said.

Earnings from garment exports have grown dramatically in recent years and are expected to top US$2 billion in 2017-18. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Zaw Oo also suggested companies would reap dividends by upgrading their management practices to achieve improvements in productivity. “Having good relations between employers and workers is very important,” he said.

Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population permanent secretary U Myo Aung agreed.

“Although the government sets the rate, employers might adjust their payment rates to motivate good workers,” he said.

Union leaders say one of the biggest challenges they face is the attitude of employers. They say that instead of negotiating courteously, most employers have a hostile attitude towards organised labour and regard union members as the enemy.

Ma Moe Moe Aye, a labour leader at a Yangon garment factory, said its owners unfairly pressured her and her colleagues.

A worker at a garment factory in Hlaing Tharyar Industrial Zone, on the western outskirts of Yangon. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

“They pressured us indirectly, such as by discriminating in favour of non-union workers,” she said.

Although employees at big enterprises complain about unfair treatment, workers in the informal sector sometimes enjoy better pay than the minimum wage.

Ko Kyaw Kyaw runs an aluminium decoration business that has seven workers, the newest of whom is paid K5,000 a day despite being unskilled. After about six months salaries are increased to K6,000 or K7,000, said Kyaw Kyaw, whose business is neither licensed nor registered.

Zaw Oo said encouraging informal businesses to register and pay taxes is one of the biggest challenges for building Myanmar’s macroeconomy and could take a decade to achieve.

“Step by step, we need to get them into the formal sector,” he said. “If so, we can reduce limitations to reach every employee or worker to be able to earn the minimum wage.”