A loosening of regulations under the former government has encouraged banks to expand rapidly and diversify their offerings.

By PETER JANSSEN | FRONTIER

WHEN GENERAL Ne Win, in his drive for socialism, nationalised all of the country’s banks in 1963, each of the 24 institutions was provided with a new, lacklustre name: People’s Bank No. 1, People’s Bank No. 2, and so on. Continuing the drive for pure socialist banking, by 1970 he had merged them into a single, massive institution – the People’s Bank of the Union of Burma.

Fifty-four years later, Myanmar banks are still trying to distinguish themselves. Slowly, they’re getting there.

“Before 2011 there was nothing much the banks could do. Opening new branches was restricted, so the banks’ growth was restricted,” said U Kyaw Lynn, chief executive officer of CB Bank, which is now ranked among the leading four private banks. CB Bank now has 155 branches, 240 “Easi Mobile Agents” and 450 ATMs nationwide. It is branding itself as a “digital bank”, offering mobile banking services to its customers through e-wallets and mobile phone apps.

U Kyaw Lynn, who is also general secretary of the Myanmar Banks Association, acknowledged that the better times for the banks started with the nominally civilian rule of former President U Thein Sein. “They moved much quicker and many things could get done.”

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

U Kyaw Lynn, executive vice chairman & CEO of CB Bank. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

But Myanmar’s banks are starting from a low base, and not just because of Ne Win’s disastrous policies. Myanmar suffered its most recent, and a singularly devastating, financial crisis in 2003, thanks to poor supervision of the private banking sector.

The crash of 2003, when several banks eventually went under – including the country’s largest, Asia Wealth Bank – has left a deep distrust of the formal banking system. This has yet to disappear, with only 10 percent of the Myanmar population holding bank accounts, according to some estimates.

Another factor behind the low rates of formal banking is the troubled history of the kyat. From demonetisations to inflation, it has been a poor savings vehicle – particularly relative to gold or real estate – because the local currency tends to lose value faster than the interest on deposits can increase it.

It is not only distrust of both the banks and the currency that keeps Myanmar’s population underbanked. There are just not many bank branches out there, and remoter areas often lack any private banks at all. Nationally Myanmar has an estimated 1,500 bank branches, but two state banks – Myanma Economic Bank and Myanmar Agricultural Development Bank – account for about one-third of these. To put this in perspective, in neighbouring Thailand, Bangkok Bank alone has 1,200 branches.

/></p> <p>KBZ Bank is Myanmar’s largest private sector bank and has an estimated 389 branches nationwide. It has branches even in Chin State, the country’s poorest region. “There are a lot of Chin people living in the USA and they want to send remittances to their families, mostly through Western Union,” said U Than Lwin, a former deputy governor of the Central Bank of Myanmar and now a senior consultant to KBZ.</p> <p>KBZ recently became the first Myanmar bank to receive permission to open a representative office in Thailand and is seeking a full bank branch there. It is targeting the 2-3 million Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand, who represent a good portion of the remittances sent home. “If we have a presence there it’s easier for us to attend to the migrant workers with the cooperation of the Thai banks,” Than Lwin said. In June KBZ also received permission to open a representative office in Singapore, another hub for Myanmar workers.</p> <p>Remittances are still big business for Myanmar’s banks. The World Bank estimated Myanmar’s total remittances at US$3.5 billion in 2015 but banking sources say it could be closer to $5 billion, or 7.8 percent of Myanmar’s gross domestic product (GDP) of $64 billion. All the banks are going after the remittance pie, which ranks as their second main revenue-spinner after loans, even though competition has brought transaction fees down to 0.05 percent. But banking on remittances is not necessarily where the future lies for a domestic economy that is growing at 8 percent and desperately in need of financial services.</p> <p><img class=

“If you talk to Myanmar bankers they think banking is the remittance business,” said Mr Tim Scheffmann, a former adviser to the Central Bank of Myanmar and now CEO of MyPay, a soon-to-be-launched financial services technology product, or FinTech. Mobile money operators and FinTechs will also be targeting the remittance market, pushing the banks to focus on new products. “There is so much more to banking than remittances. It’s lending, cash-flow lending, taking risks financially, portfolio management and wealth management that is not even there yet,” said Scheffmann.

The new government under the National League for Democracy has made financial inclusion one of its core policy goals. Pressure is expected to build on the banks to increase their lending portfolios, which have tended to nurture the elite in the past. “What we’re thinking is that our people just deposit our savings at the banks and all those funds are lent to people with land and property,” said one senior adviser to the NLD’s economic management team.

But notwithstanding these good intentions, the banks continue to face regulatory constraints from the central bank, such as fixed interest rates and a traditional dependence on immovable property as collateral for loans.

To be fair, the CBM has shown some flexibility on the collateral issue. “We can use fishing boats as collateral,” said U Hla Nyunt, deputy managing director of privately owned Global Treasure Bank, which was formerly the Myanma Livestock and Fisheries Development Bank. Last year, 31 percent of Global Treasure’s loans went to the livestock and fisheries sector, which is targeted by the bank’s 120 branches. “We also use community group guarantees on loans, or group debt,” he said. Community lending involves a group of more than five people taking on group responsibility for debt repayment, and is often used by farmers to access credit.

Myanma Apex Bank, part of the Eden Group, is also targeting agricultural lending. With a network of only 75 branches nationwide, it needs to specialise to stay competitive.

MAB has received central bank permission to use farmers’ land tenure rights as collateral for small loans of about $350 per acre each growing season.

An Asia Green Development Bank ATM. (Maro Verli / Frontier)

“Now we have been lending for two rice seasons. So far we haven’t had any defaults or NPLs [non-performing loans],” said U Chit Khine, who chairs both MAB and the Myanmar Rice Federation. “The agricultural sector is our first priority. We are targeting the whole network. We are now studying warehouse financing … The second priority sector is SMEs.”

With only 60 branches, Yoma Bank is trying to capitalise on its reputation for good governance and a strong team of Myanmar “repatriates” recruited from abroad. Both the International Finance Corp of the World Bank and Asian Development Bank have programs with Yoma.

“Yoma will remain a business bank. We serve the SMEs,” said Mr Hal Bosher, the bank’s CEO. “Where we do well is with regional and international corporations. They like us because of our English-speaking repatriates and because of our good governance.”

Some local banks are just betting on getting big quick. “Currently we have 158 branches. We aim to have 250 branches by the end of this year,” Ko Myo Win Yee, senior general manager and head of E-Channel Financial Inclusion Banking, AYA Bank. “We are a very aggressive local bank. We are a medium-sized bank but we are trying to be big,” he told a recent FinTech seminar.

All of the bigger banks – KBZ, AYA, CB, Myawaddy Bank, Yoma and MAB – are investing heavily in information and communications technology systems to make sure they don’t miss out on the growth potential from mobile banking. Most of these bigger banks are also actively expanding their branch networks to increase their deposit base, which has been growing at a rapid annual rate. This in turn enables them to expand lending, and helps to explain why Myanmar’s bank credits have been shooting up at about 50 percent per annum since 2012. “Our deposit base is increasing 35-50 percent a year, so that’s why loans are growing about the same,” said CB Bank’s Kyaw Lynn.

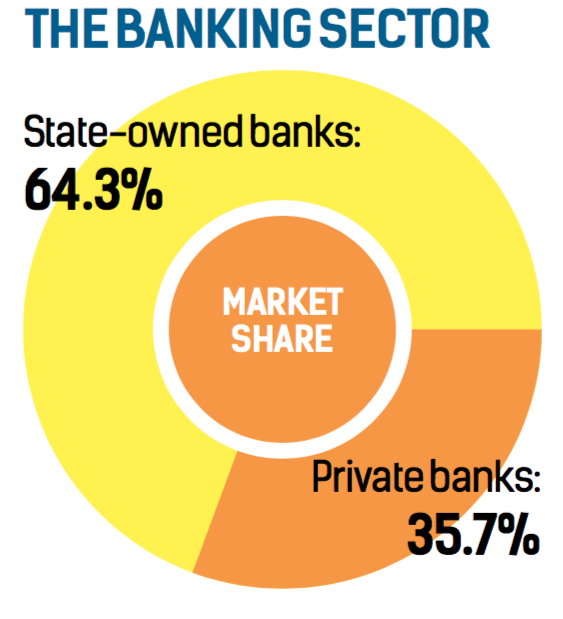

But the majority of Myanmar’s banks don’t have the wherewithal to invest in expensive computer systems or even more expensive new branches (one new branch can cost up to $5 million). With 29 licensed banks – four state-owned and 25 private – and with several more in the process of applying for licences, Myanmar is underbanked in terms of financial inclusion but arguably overbanked in terms of the number of institutions. This raises questions about the long-term viability of some of the banks, and even whether failures could be on the horizon as the system gets more competitive and the technological and branch network divide between the big and the small banks widens.

But given the long shadow of the 2003 crisis, which still hangs over the system, it is unlikely that the central bank will allow any of the weaker banks to go out of business, those in the sector say. It would simply be too damaging for customer confidence. “We believe the government will encourage mergers and acquisitions,” said Chit Khine. “I think we need to go in that direction in the future.”

This article originally appeared in Frontier Myanmar’s Banking and Finance special edition, published in July 2016.