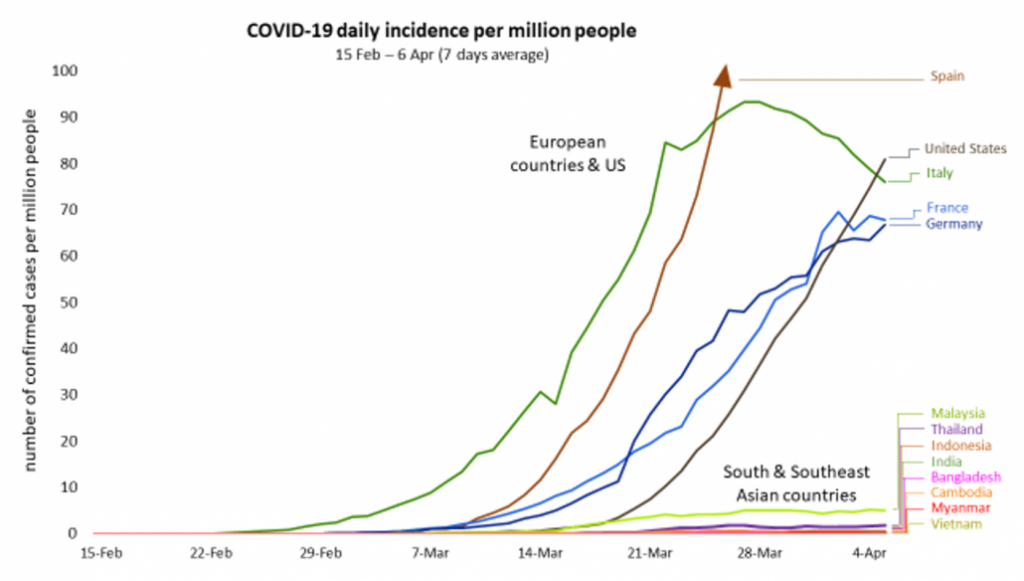

The transmission of COVID-19 has been much lower in tropical countries than in China’s Wuhan, Europe and the United States, and strict adherence to prevention measures – rather than a full lockdown – might be sufficient to limit its spread in South and Southeast Asia.

By DR FRANK SMITHUIS | FRONTIER

ALTHOUGH hospitals in Europe and the United States have been overwhelmed by the massive number of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, the situation in tropical Asia is dramatically different.

Several thousand cases have been reported in South and Southeast Asia during the past three months, but the epidemic has a completely different – and much slower – transmission dynamic. What is the likely explanation for this and should it have consequences for managing the epidemic in Asia?

COVID-19 global pandemic

The epidemic has a completely different – and much slower – transmission dynamic in South and Southeast Asia than Europe and North America.

Figures compiled by Worldometer show that as of April 8 more than 1.45 million COVID-19 cases had been reported globally, and the virus had killed more than 83,000 people.

The outbreak began in Wuhan, capital of the Chinese province of Hubei. On December 31, China reported several cases of unusual pneumonia in Wuhan, a river port city of 11 million people. On January 13, the first case outside China was reported in Thailand, in a woman who had arrived from Wuhan. Other countries, including Japan, the United States, Nepal, France, Australia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan reported cases in the following days.

From then, a rapidly increasing number of countries reported COVID-19 infections. Yet, in January and February, the main disease burden remained limited to China with only small numbers of cases in other countries. It was only at the end of February and in early March when serious outbreaks developed in other countries; first in Italy, followed by other European countries, and then the US. In countries where the number of cases was high, the disease overloaded the healthcare system and a rapid increase in deaths followed. Fear and anxiety spread rapidly worldwide.

In comparison, the number of new cases in South and Southeast Asia has remained low. Although many South and Southeast Asian countries reported their first cases in January, transmission did not explode. A substantial number of these cases were people infected abroad. The local outbreaks that did occur were often linked to heavily attended gatherings (mass religious events in Malaysia and India, and a boxing match and a dinner party in an air-conditioned room in Thailand), but local transmission has generally remained low.

In Wuhan, Europe and the US, once local transmission was established, the number of new cases rose rapidly from a few to thousands or even tens of thousands a day. In South and Southeast Asian countries this has not happened and the numbers of new cases are actually quite low and increasing only slowly (see graph below).

Testing

Some have suggested that limited testing is responsible for the low number of cases. It is clear that if you do not test, you don’t identify positive cases, and it is safe to say that there are more cases than have been reported because of the low testing rates. However, it is extremely unlikely that large-scale transmission has occurred undetected. Large numbers of people with severe COVID-19 symptoms would have flooded hospitals and many deaths would have followed. This could not have occurred unnoticed.

Coronavirus characteristics

It is believed that coronaviruses are spread through close proximity with an infected person and inhaling droplets generated when they cough or sneeze, or by touching a surface on which droplets have landed and then touching the eyes, nose or mouth.

Coronaviruses are common causes of “colds”, but this new SARS-CoV-2 is much more dangerous. The crude mortality of COVID-19 is higher than “the flu” which infects up to 1 billion people a year and kills between 290,000 to 650,000. The estimated COVID-19 reproduction number, or R0, (the average number of people that can be infected by one infected person), is believed to be higher than that of the “flu”, and while this number remains above 1, the pandemic grows. But the reproduction number is not the same for all countries, therefore causing more or less transmission.

Transmission intensity

It is not yet entirely clear why the transmission intensity is different in tropical Asia than in China, Europe and the US, but a number of explanations have been proposed.

High temperatures and humidity influence viral viability. Contaminated surfaces are known to be significant vectors in the transmission of infections in hospital settings as well as in the community. However, the persistence of viruses on contaminated environmental surfaces and the longevity of viable virus are affected markedly by temperature and humidity. Studies have demonstrated that SARS survived for two weeks in low temperature and low humidity conditions found in an air-conditioned environment. However with increased heat and increased humidity viruses were more fragile, which could reduce the transmission of the virus in sub-tropical and tropical countries.

Other explanations have been suggested that are linked to South and Southeast Asian countries, including BCG vaccination coverage, societal social distancing and diet, as well as a variety of more imaginative reasons.

Control measures

Because the transmission intensity in South and Southeast Asia appears to be very different, the package of measures necessary to contain the virus (or to reduce the reproduction number below 1) is also likely to be different. It is not a matter of “one strategy fits all”. More measures are required when a virus is widespread and transmits fast. In Wuhan, European countries and the US, with the epidemic out of control, lengthy lockdowns were imposed to slow down the high transmission.

These lockdowns were first and foremost deemed necessary to slow down the spread of infection and consequently reduce the burden on overwhelmed healthcare systems. And, although those affected suffered from stress and boredom, nobody starved to death. The people in these so-called “rich” countries usually have social security and enough economic reserves to survive. This is very different for the people in South and Southeast Asia. Long-term lockdowns, for weeks or months, would be devastating in Asian countries, where hundreds of millions live hand to mouth and have no reserves to buy food if they lose their jobs.

The three-week COVID-19 lockdown of India’s 1.37 billion people has stranded millions of domestic migrant workers and left people scrambling for food and other basics amid an ensuing harsh and often violent crackdown by police. The Indian Prime Minister, Mr Narendra Modi, who ordered the lockdown, apologised but justified the lockdown by saying, “I understand your troubles, but there was no other way to wage war against [the] coronavirus. … It is a battle of life and death, and we have to win it.”

But was this really necessary? Are long-term lockdowns required for South and Southeast Asia? At this stage of the epidemic, with local transmission still very low, less intense measures have proven sufficient to keep the epidemic low. Strict adherence to prevention measures, including social distancing, avoiding large crowds, hand washing, covering mouth and nose while coughing, and wearing face masks, combined with intensive testing and contact tracing might be sufficient to limit the spread. These measures alone, at least for now, could be sufficient and avoid the dramatic socio-economic consequences of long-term lockdowns.

The future

There are many factors that can influence the future course of the epidemic; human behaviour, immunity, climate, discoveries of treatment, prophylactic treatment and – when available – vaccines. Nobody can foresee the dynamic of COVID-19 in Asia, but it is likely that the epidemic will last for a long time, probably years instead of months. The risk of transmission will only decline when 60 percent to 70pc of a community has developed immunity, either through natural infection or vaccination. Even when transmission is halted successfully, as it has been in Wuhan, it is likely that the virus will recur, as the vast majority of China’s population (more than 99pc) is not yet immune and remains vulnerable to new outbreaks.

With transmission in tropical Asia significantly lower than in the West, the same extreme lockdown measures as taken in Wuhan and the West would be devastating for the poor in South and Southeast Asian countries. Proper implementation of basic control measures, including testing of suspected cases, followed by contact tracing and isolation, are likely to be sufficient to avoid larger outbreaks. This should be combined with large scale testing, to better understand and monitor the spread and the dynamic of the epidemic. Containment measures should be adapted if necessary.