The government’s decision to raise electricity prices is commendable, but creating an independent regulator would take politics out of the country’s power supply.

This is not a government known for making brave political decisions. But on June 25, it announced a much-needed increase in electricity prices, for both households and businesses. The new pricing came into effect on July 1.

In reality, the government didn’t have much choice. Electricity subsidies are already close to US$500 million a year and threatening to balloon out of control. Still, to announce an increase of this size relatively close to an election was commendable.

The price hike will hurt many middle-income households. Those using the relatively modest sum of 200 units (a unit being one kilowatt hour) a month will see their bill rise from K7,500 to K17,550. The era of dirt-cheap power is over.

But there’s a bigger picture. Less than 50 percent of households in Myanmar have access to power from the national grid. Those connected to the grid are, with few exceptions, better off financially than those who are not. That means the subsidies have been going to the wealthiest households in the country. Not only that: the subsidies have made it more difficult for the government to expand access to electricity.

This is inherently unfair and only reinforces economic inequality.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

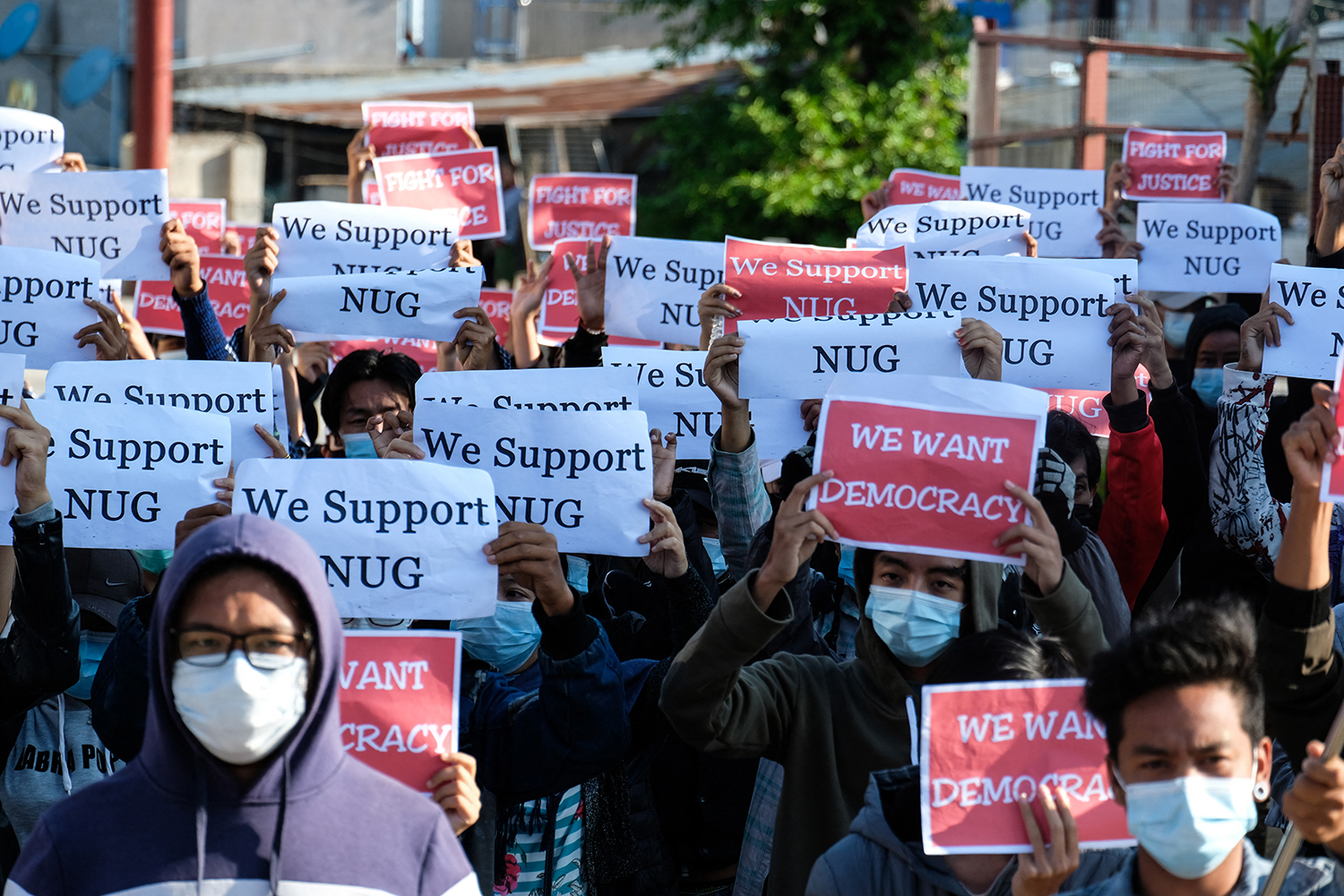

Inevitably, there have been some criticism and protests in the wake of the announcement. The government needs to hold the line; to back down now would be a disaster.

Having given itself more financial leeway, it must now focus its attention on improving supply. The increases should be presented to the public as a bargain: pay the higher rates and you’ll receive a more reliable supply at all times of the year.

The government has already moved in this direction. Three days after the new pricing was announced, the Electric Power Generation Enterprise issued a tender for five emergency power contracts, totalling 1,040 megawatts. Three of these will be powered by imported liquefied natural gas. These will be expensive to operate and would have been catastrophic for the budget bottom line if prices had not increased.

The five-year contracts should ensure a reasonably steady electricity supply all year round – including the March-May hot season, which this year saw a spate of power cuts, noticeably worse than previous years – and enable the government to provide power to some of those who are not yet connected to the grid.

The emergency power will buy the government time to pursue long-term solutions to Myanmar’s power crunch. It has a range of options, from large and small-scale hydropower to power imports, solar photovoltaic or LNG-to-power. New offshore gas fields should also come online in the next five to 10 years, providing both income from exports and gas for domestic power generation.

But the emergency contracts would probably not have been necessary if the National League for Democracy government had increased prices the day it took office.

Subsidies might seem like a throwback to the socialist era, but in fact they are relatively new. Since the 1970s, the government has mostly turned a small profit from power generation. The small loss in 2015-16 was the first in more than a decade. But since then the losses have grown significantly because the government has relied on more expensive sources of power to meet growing demand.

Stagnant pricing has exacerbated these losses. Electricity rates haven’t changed since April 2014. The decision not to raise prices has cost the country well over $1 billion over the past three years.

To avoid repeating this mistake, power prices will need to be adjusted on a more regular basis. Further increases will almost certainly be necessary in the years ahead. But, like the current one, future governments will inevitably be reluctant to raise prices for fear of losing votes.

An independent regulator that monitors the cost of supply and changes prices accordingly would take much of the politics out of the equation.

Yes, the government of the day would lose control over prices. But it would also not have to take responsibility for the regulator’s decisions.

Myanmar does not have a culture of independent market regulators. This is an opportunity to start building one.