Terrified civilians are bearing the brunt of the upsurge in fighting in northern Shan State, as death and displacement rise due to attacks for which no armed force is claiming responsibility.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

Photos STEVE TICKNER

WHEN MORE than 70 troops from the Tatmadaw’s Infantry Battalion 68 deployed in Kone Sar village, about 13 kilometres northeast of Lashio town in northern Shan State on August 17, the residents were fearful. Their nerves had been on edge since the previous day, when Tatmadaw helicopter gunships had launched attacks on suspected targets in nearby farmland and jungle-clad hills.

The villagers had sought refuge in a small monastery at one end of Kone Sar. When the newly arriving troops moved into the monastery compound, set up two mortars and fired two rounds into the village, residents knew they needed to take cover further away.

They made the decision to flee, leaving behind just one person from each household. Starting from the morning of August 18, scores of Kone Sar villagers fled on foot to the monastery at Mong Tin village, a few kilometres away.

Among the departing villagers later that night were Sai Lon Aye, 42, and Sai Thein Kyi, 56. They were discussing what to carry and how long they might be away when they heard mortar fire and began running for cover. Thein Kyi was the faster runner. When he looked back, he saw Lon Aye’s body sprawled on the road; shrapnel from a mortar had struck the back of his head, killing him instantly.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Shan women who fled the village of Kone Sar take shelter at a nearby monastery in Mong Tin village after a mortar shell killed a resident, Sai Lon Aye (top) and members of a rescue team carry the body of Sai Lon Aye. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Lon Aye is survived by his wife, Nang Aye Kyin, 41, and their twin children, a boy and a girl aged 11.

“I can’t stand this anymore; now I’m left with only my children,” a distraught Aye Kyin told Frontier later at Mong Tin monastery, beside her crying children. Her son, Saing Seng Pwin, had only recently undergone a ceremony to become a novice monk.

Aye Kyin said her husband was looking forward to harvesting the crops he had been tending for months. “How can I do it by myself?” she said.

Lon Aye was killed three days after three members of the Northern Alliance launched brazen coordinated attacks on military, infrastructure and other targets in Lashio and Nawngkhio townships and at Pyin Oo Lwin in Mandalay Region.

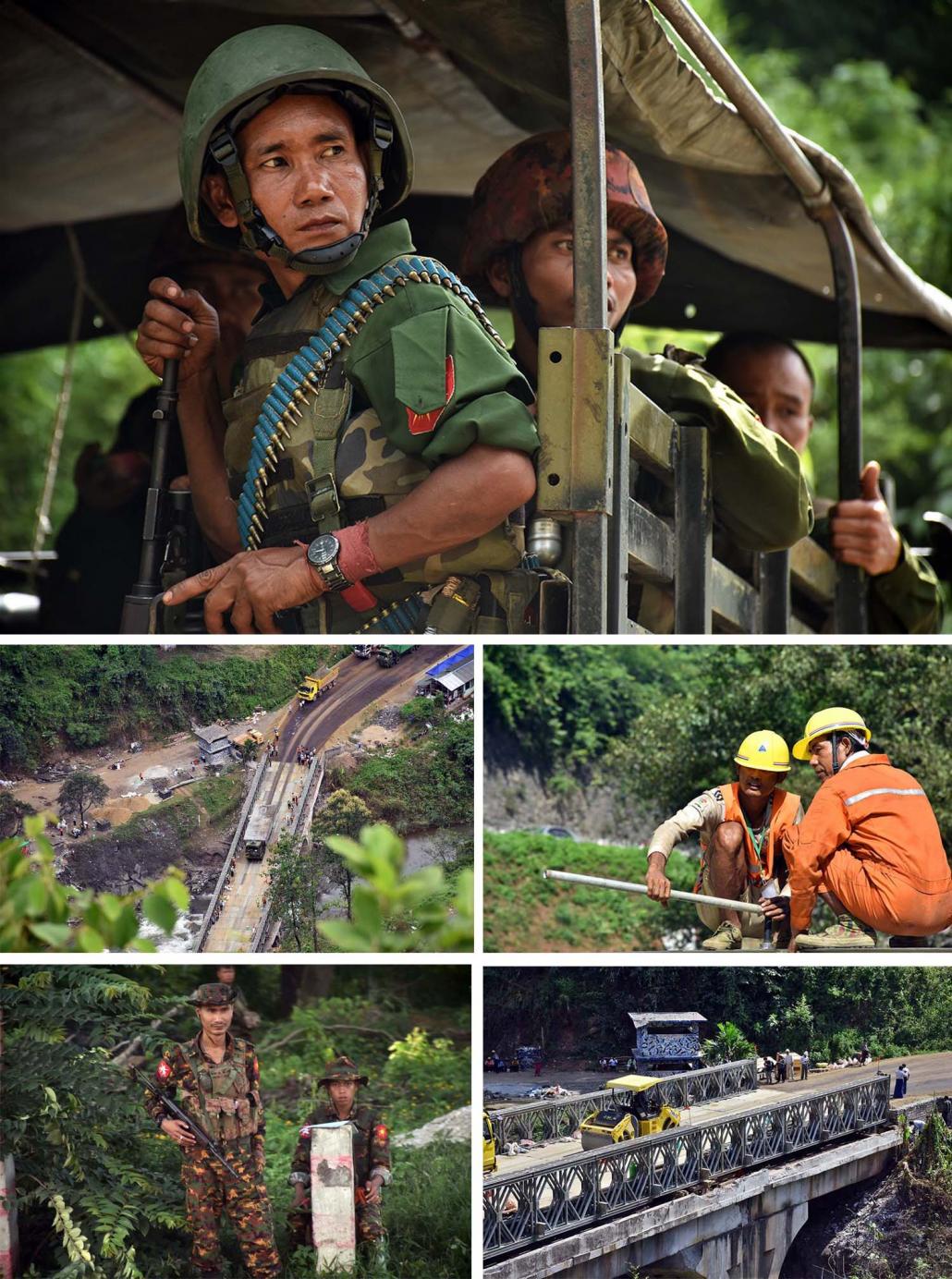

The attacks by the Northern Alliance allies, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and Arakan Army, killed seven security personnel at a guard post at the Goktwin bridge in Nawngkhio, and left at least three people dead at the Defence Services Technological Academy in Pyin Oo Lwin, one of several Tatmadaw training institutions in the town. The bridge, on the main trade route with China, was also badly damaged by mortar fire, and re-opened on August 20 after emergency repairs.

The attacks almost immediately sparked clashes and military operations across Lashio and Kutkai townships in northern Shan State, closer to the border with China. In the fighting between the three groups and the Tatmadaw, it was often unclear which side was responsible for civilian casualties and some of the incidents that caused damage to homes, buildings and infrastructure.

“Both sides in this fighting should have taken greater responsibility to avoid harming innocent civilians,” Sai Han, chair of the Tai Youth Organisation in northern Shan, told Frontier in Lashio on August 24.

“If this reckless behaviour continues, the lives of our civilians can get worse. All of the people in northern Shan are in a state of alarm because they do not know when the fighting will end,” he said.

Northern Alliance forces destroyed the Goktwin Bridge, a chokepoint on the Mandalay-Muse Highway, in the August 15 attacks. Five days later, a new bridge was opened, with a Tatmadaw convoy of about 50 vehicles the first to pass. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Sai Han and other community service leaders in Lashio and nearby Kutkai Township strongly believe that one of the Northern Alliance members was responsible for the death on August 17 of U Tun Myint, chairman of the Lashio Youth Support Social Association. He suffered a fatal shrapnel wound to the head when an explosive device overturned the van he was driving. Two of the three passengers in the van were also injured in the incident, which occurred as they were travelling to a village about 20km from Lashio to rescue people injured in fighting.

Peace activists and conflict monitors condemned the attack on a clearly marked rescue vehicle, saying it amounted to a breach of the Geneva Convention.

TNLA spokesperson Major Mai Aik Kyaw has said he did not know if the van was targeted by one of the three Northern Alliance members or the Tatmadaw.

Speaking after Tun Myint was buried at the Muslim cemetery at Lashio on August 17, a leader of the Islamic community in the town, U Aung Than, said President’s Office spokesperson U Zaw Htay had responded to the attacks in northern Shan and Mandalay Region by saying that the government had opened the door to peace.

“But, the situation of our people is that we still have to shut ourselves inside our homes [when there is fighting]; they should solve these problems as soon as possible by holding talks instead of shooting each other,” he told Frontier.

Tun Myint’s distressed widow, Daw Tin Tin Aye, said the “reckless” incident had killed “a valuable person who was on his way to help others.”

“They should give more consideration to whether the target is good or bad,” she said, referring to those behind the attack.

The wife of a retired Tatmadaw officer stands in front of her home in Lashio Township on August 18 after it was damaged during fighting. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

On the same day that Tatmadaw troops deployed at Kone Sar village, a house on the outskirts of Lashio town was hit by an explosive device, injuring Daw Hla Saw Yee, and her daughter and grandchild, both of whom were admitted to hospital after the incident with non life-threatening injuries.

Her husband, a retired Tatmadaw sergeant, was visiting his native Rakhine State when the explosion shattered the house in the settlement, which was developed for the families of Tatmadaw veterans.

“I don’t know who did it,” Hla Saw Yee told Frontier in the ruins of her house. “We are staying in the house of a relative. The only fortunate thing is that my 13-year-old was at school when the incident occurred.”

With her husband away, Hla Saw Yee said she had no money to repair the house and did not know what to do.

Following the incident, most of the residents of the settlement and those from three nearby Shan villages fled to Lashio town to seek refuge at its Mansu monastery, which was sheltering more than 1,000 internally displaced people on August 18.

The monastery’s abbot, Sayadaw U Ponnyananda, said he deplored the fighting.

“The fighting should end immediately and the two sides should start talking because if that does not happen the suffering of the people in northern Shan will get worse,” he told Frontier. The monastery has often sheltered people displaced by fighting since the time of the Union Solidarity and Development Party government and has received considerable support from the government and the Tatmadaw.

Children displaced by recent fighting in northern Shan State eat at a monastery in Kutkai Township. Thousands of civilians have sought refuge at monasteries in northern Shan State. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

The number of IDPs sheltering at the monastery and other locations has steadily increased since hostilities began escalating in northern Shan on August 15.

In Kutkai Township, there are 1,500 people sheltering in four IDP camps. Salaung Zau On, the in-charge of IDP affairs for the Kachin Baptist Convention in Kutkai, said most of displaced people in the camps were from Ho Naung and Nam Kut villages. The villages are on the 45km stretch between Kutkai town and Nam Hpat Kar town on the main highway to Muse, the trading centre on the border with China. “We don’t know when it will be safe for them to go home,” he said.

About 32km east of Lashio is Man Kaung, the main village in the Man Kaung Mon Yan village tract, where the leader of a militia group and his wife were killed in an apparently targeted attack on August 22.

The home of U Win Maung, 61, the leader of the Mong Yan militia, and his wife, Daw Aye Mya, was bombarded with bullets, hand grenades and M79 grenades in the attack, which terrified the 200 residents of the village. Aye Mya appeared to have been shot in the back of the head, while Win Maung died in a toilet at the rear of the house after his assailants shot him through the locked door.

Win Maung is a former member of the Tatmadaw, and as his body and that of his wife were being transported to Lashio hospital in an ambulance, it was stopped at a Tatmadaw checkpoint between Man Kaung and Lashio manned by several troops who had served with him. One of the soldiers, a captain, wept when he saw Win Maung’s body and offered a Buddhist prayer for the liberation of his soul.

The attack came three days after the three Northern Alliance members issued a statement warning that any members of government security forces found in operational areas would be “duly taken care of for the sake of self-defence”.

The August 17 statement referred to the Tatmadaw but warned specifically that members of the Myanmar Police Force and uniformed members of paramilitary groups would be regarded as members of ancillary forces on active duty.

It also warned local paramilitary forces against participating in operations with the Tatmadaw and advised them to remain at home with their families.

A truck and motorcycle destryoed during the assault on the home of Mai Yan militia leader U Win Maung. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

The bodies of Win Maung and Aye Mya were found in the remains of their two-storey house and collected the next day by a Lashio-based emergency response group, the Tai Youth Network. Their bodies reached Lashio General Hospital on August 21.

Their grandson, Maung Aung Nyein Chan, 13, survived the attack.

“Grandfather told me to run when the attack started,” the grieving boy, who was raised by his grandparents, told Frontier.

As in the recent other attacks in the area, there was no claim of responsibility.

The village-tract administrator, Sai Seng Nyunt, said residents had sought cover when they heard the sound of grenade launchers and automatic weapons as the attack began.

“Though we have two militia groups in the village, they do not have any weapons, so people had to hide until the attack was over,” he told Frontier.

Older village residents said there had been skirmishes around the village tract in the past involving light weapons but it was the first time they could recall grenades and RPGs being used.

Unexploded ordnance – two hand grenades and one M79 grenade – were still at the scene of the attack when Frontier arrived in the village on the morning of August 21.

Despite suspicions that one of the three Northern Alliance members were behind the attack, the TNLA’s Mai Aik Kyaw said he did not know who was responsible.

He said the only way to end the fighting was through dialogue. “We have made clear that we are acting in self-defense and if the Tatmadaw chooses to respond only with warfare, there will be more fighting,” he said.

In an indication that the attacks are likely to continue, one person was killed in a raid on a security forces checkpoint at Yay-Pu, on the road between Hseni Township and Lashio at dawn on August 24.

An elderly, ill Ta’ang woman in her 90s rests at Kho Lon monastery near Kutkai after fleeing fighting. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Members of community rescue and emergency response groups in northern Shan are disappointed that there has been no comment about the fighting by President U Win Myint, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Tatmadaw Commander-in-Chief, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

On August 16, the day after the attacks by the Northern Alliance trio, Min Aung Hlaing left for Russia to attend the International Army Games. He has not publicly commented on the fighting since he returned to Myanmar on August 20.

Referring to Win Myint, Aung San Suu Kyi and Min Aung Hlaing, Sai Han expressed disappointment that national leaders have had nothing to say about the fighting in northern Shan.

“They are the people all the citizens are relying on [to say something]. I believe that all the people in the war zones want to hear something from them or to see a commitment or action [to do something about the fighting], he said.

“I feel really sad that they have had nothing to say since the attacks began 10 days ago.”