There are many reasons why more than 500,000 people have fled to Bangladesh in the aftermath of the August 25 attacks.

By SITHU AUNG MYINT | FRONTIER

ON OCTOBER 2, Rakhine State administration officials met a group of about 10,000 people – mainly Muslims who identify as Rohingya – who had arrived at an area between Thinbawhla and Thayagon villages in Maungdaw Township on their way to Bangladesh.

This is evidence that almost a month after the Tatmadaw was said by State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to have ceased its clearance operation in northern Rakhine on September 5, calm has returned to the area. Also on October 2, Minister for the State Counsellor’s Office, U Kyaw Tint Swe, travelled to Dhaka for talks with the Bangladeshi Foreign Minister, Mr Abdul Hassan Mahmood Ali, to discuss the topic of repatriating refugees. Despite these positive developments, the flight of Muslim refugees to Bangladesh has continued. This shows that the exodus is not only because of rough treatment by the Tatmadaw during the clearance operation, as some foreign media and governments have been saying. The problem is more complicated than that.

Let’s begin with the Tatmadaw and the clearance operation it launched in response to the attacks by Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army extremists in northern Rakhine on August 25. A Tatmadaw news release said that in the five days between August 25 and 30, the bodies of 370 extremists were recovered. This means an average of 74 extremists were killed on each of the five days after the attacks, a casualty figure that suggests the clearance operation was fierce. It would be true to say that the residents of Muslim villages affected by the operation had to run for their lives.

However, it is also clear that the 11-day Tatmadaw operation was unable to cover all villages in northern Rakhine with a total population of 400,000 to 500,000 Muslims. This means that only a small number of those who fled to Bangladesh were directly affected by the clearance operation and that the great majority of the refugees had not even seen Tatmadaw troops.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Muslim villagers in northern Rakhine fled in fear of an expected Tatmadaw response when they heard of the coordinated ARSA attacks on 30 police posts and a military camp on August 25. Extremists and villagers understood very well that there would be a harsh reaction from the Tatmadaw because of the way it responded to the ARSA attacks on border police posts in October last year. It can be imagined that Muslims from many villages began heading to the border as soon as they heard about the August 25 attacks.

An important factor is the strategy and objectives of ARSA. It knew that the villagers it had recruited and armed with daggers, swords, catapults and improvised bombs had no chance of inflicting serious casualties on the security forces in the August 25 attacks. The extremists who survived the attacks fled immediately to Bangladesh among the refugees. ARSA knew that the more refugees that fled to Bangladesh, the more attention the situation would receive from the international community and the result would be more pressure on the Myanmar government. One month after the Tatmadaw launched the security operation, Muslim villagers who remained in northern Rakhine continue to be pressured to leave for Bangladesh by the use of various tactics, including assurances that life there is better.

Another reason for the exodus is disruption to livelihoods. When there is conflict in Rakhine, the authorities respond by imposing a curfew. Muslims, who are forbidden from travelling outside their townships at normal times, dare not leave their villages at all for fear of being arrested on suspicion of links to the extremists. There have been many such arrests, and a consequence is that Muslims whose livelihoods depend on being able to leave their villages, to farm their land, fish or forage for food in the jungle, are unable to support themselves. Without food and a livelihood they face the prospect of starvation. There is a concerted effort to encourage them to join the exodus. They are told that in Bangladesh they will be safe and be fed and if they are lucky, accepted for resettlement in a third country. This is why people are still crossing the border.

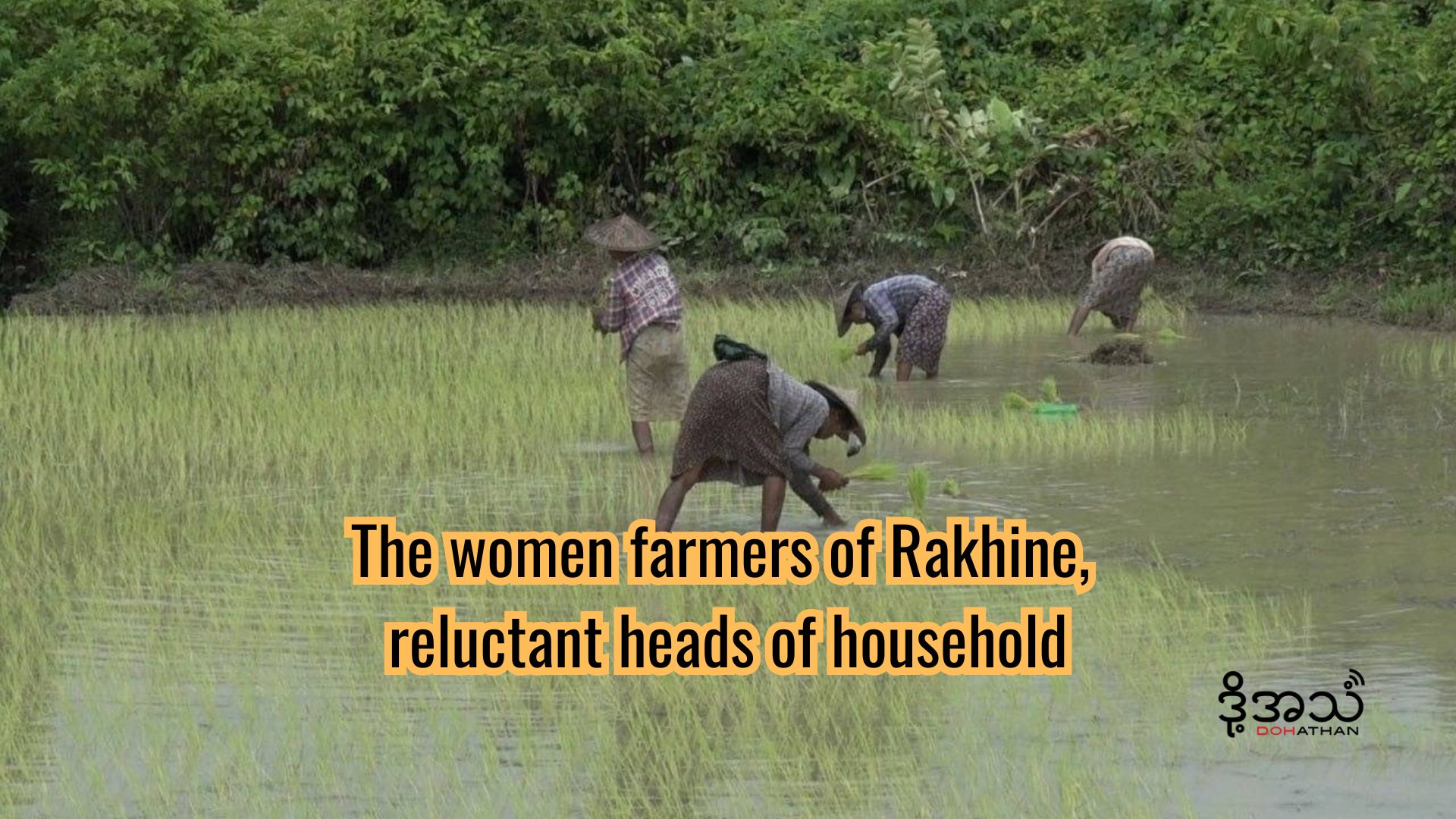

The fleeing Muslims also include farmers who own their land and grew crops or raised cattle and goats. They were reluctant to abandon their land and livestock but after a majority of the Muslim population in northern Rakhine left for Bangladesh, they did not want to remain there as members of a minority and joined the exodus half-willingly. There are many such people.

For the reasons outlined above, it can be seen that the reason why hundreds of thousands of people who identify as Rohingya have crossed into Bangladesh is not only because of the Tatmadaw’s clearance operation, as has been claimed by foreign media and many in the international community.