The last ruler of the princely Shan state of Hsipaw returned home from the United States in 1954 with grand development ideas but was arrested during the Ne Win coup in 1962 and never seen again.

Words & Photos BRENNAN O’CONNOR | FRONTIER

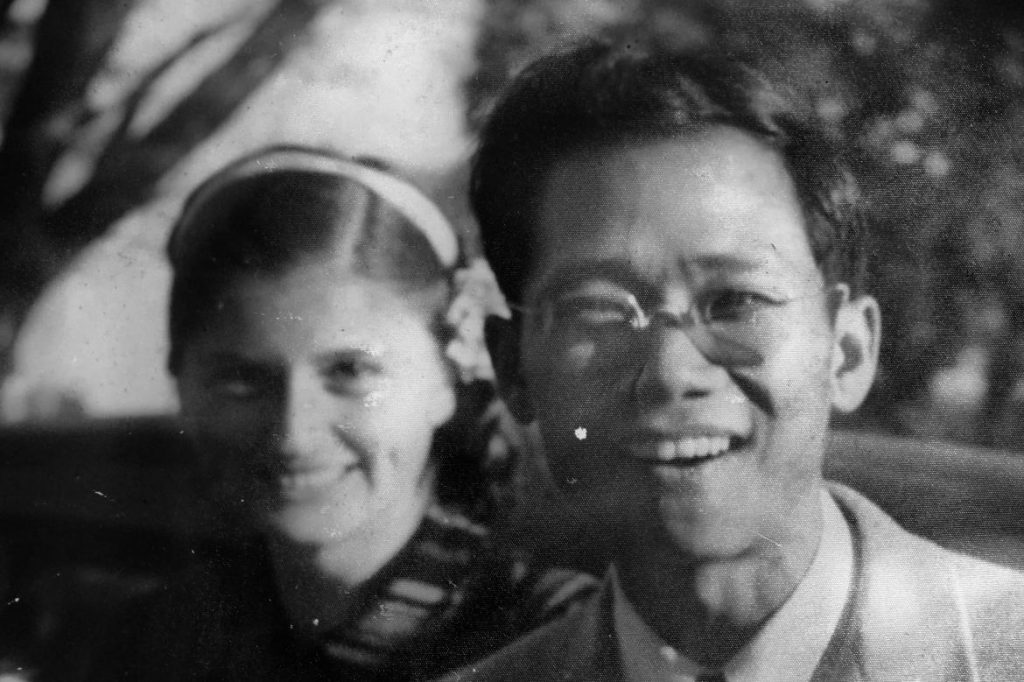

In a framed portrait photograph, the last Sawbwa of Hsipaw, the former princely ruler of one of the most prosperous Shan states, exudes both majesty and modesty. In a simple vest and tie, Sao Kya Seng proudly holds his Austrian wife, Inge Sargent. Taken soon after the couple returned from the United States in 1954, it hangs on a wall in the home of his younger, brother, Sao Ohn Kyar. About eight years after returning to his home in northern Shan State, the prince was arrested and the image was hidden away in drawers along with other photos of Shan royalty.

Kya Seng studied at the Colorado School of Mines in Denver from 1949 to 1953, obtaining a BSc in mining engineering. It was during this time that he met and married Sargent, who was to acquire the title Sao Nang Thusandi, the Mahadevi (princess) of Hsipaw.

The prince, sawbwa in Shan, had ambitious plans to develop semi-autonomous Hsipaw state; an area rich in minerals and precious gems. Tractors were bought and provided to farmers to use for free. Vast orchards of oranges and other fruit were established, and experimental agricultural projects were conducted, including growing pineapple on barren hills around Hsipaw town.

“He wanted to improve the lives of the farmers around Hsipaw,” Ohn Kyar said. “At the time people were very simple.”

_dsf4668.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Sao Kya Seng’s younger brother, Sao Ohn Kyar, points to a photo of the royal couple taken soon after they arrived in Hsipaw from the US. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

In Twilight over Burma: My Life as a Shan Princess, Sargent wrote that Kya Seng wanted to alleviate poverty by developing Hsipaw’s abundant natural resources. During his time abroad the prince had developed democratic ideas that were far different to the feudal rule that Hsipaw had long known.

Many were surprised, including his wife, when Kya Seng announced that all the paddy fields owned by the palace would be given to the families who had tilled them for generations. The royal palace, also known as the East Haw, became the first of its kind to buy supplies of rice. In his role as administrator, one of the prince’s early decisions was to dismiss some top officials for corruption.

Later, Kya Seng raised eyebrows when he refused a request from a colonel in the Northern Command to host a gambling event to raise funds for the Tatmadaw. Gambling was popular among the peasant class and the prince wanted to eliminate it from his state because of the harm it often caused to families.

The Tatmadaw was becoming suspicious of Kya Seng. A telling sign came when the then Tatmadaw Chief-of-Staff, General Ne Win, snubbed an invitation to visit the prince as he was travelling through Hsipaw. Instead, Kya Seng was asked to wait at the roadside with Hsipaw’s other residents as the general’s convoy passed by.

_dsf3801.jpg

Dancers perform at a Shan National Day event in Hsipaw. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

When Burma was under colonial rule, the Shan sawbwas were largely free to govern their own affairs after swearing allegiance to the British monarch. The Panglong Agreement, the roadmap for federalism signed in 1947 by General Aung San and Shan, Kachin and Chin leaders, granted the sawbwas semi-autonomous rule and the exclusive right to secede from the Union in ten years if not satisfied.

By the mid-fifties the Tatmadaw was consolidating its power after years of battling ethnic and communist insurgencies in the aftermath of independence in 1948. Ethnic minority officers were being purged from the Tatmadaw and it was also threatening the independence the Shan had known for centuries.

In 1950, Tatmadaw forces were deployed to Shan State to fight invading Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) troops who had crossed into Burma after their defeat by the Chinese Communist Party the previous year. The KMT recruited many Shan from border areas and by 1953 controlled large areas of the state. Caught between two belligerents, that were both perceived as foreign forces, the Shan increasingly became the target of the Tatmadaw. Complaints about human rights abuses by the Tatmadaw were heard regularly in the East Haw.

_dsf4206.jpg

Shan soldiers provide security for government officials attending a graduation ceremony for Shan Youth Network English School. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

Unhappy with their unfair treatment by the Tatmadaw, which under the Union was ostensibly supposed to be defending them, Shan groups were formed to fight for independence. They sought Kya Seng’s support but he declined. As an MP in Burma’s House of Nationalities, a member of the Shan State Council and secretary of the Association of Shan Princes, the sawbwa believed the best place to resolve political concerns was in parliament.

After Ne Win seized power in March 1962 and declared himself chairman of the Union Revolutionary Council, Kya Seng was among ethnic and political leaders who were arrested. Ne Win implemented a centralised system and disastrous economic policies and Burma quickly plunged into darkness.

“At the time people were very poor; money became worthless,” said Ohn Kyar. His mother took a job as a teacher and he attended a government school rather than the better private institution that had been arranged for him by his brother.

Ohn Kyar said that under military rule no one talked in public about what happened to his brother. If they did “they put them in jail and beat them and hit them,” he said.

_dsf3271.jpg

Successive military regimes that banned public discussion about Hsipaw’s last prince have largely succeeded in erasing Sao Kya Seng from the former princely state’s history and many young people know little about his life. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

The military never admitted arresting the prince, but several people who claimed to have seen him contacted Sargent in secret. In Twilight over Burma she describes receiving a handwritten letter from Kya Seng that was delivered by a sympathetic military guard at Ba Htoo Myo military camp near Taunggyi in southern Shan State where her husband was detained and is believed to have died in 1962. Sargent was unable to get answers from the government about the circumstances of her husband’s death and she returned to Austria in 1964 with their two young daughters, Sao Mayari and Sao Kennari.

A relative of the prince by marriage, Sao Sarm Hpong, said members of the sawbwa’s family were treated like outcasts by their community under military rule.

“Were like lepers,” said Sarm Hpong. “They were afraid that if they associated with us they would get in trouble.”

_dsf4769.jpg

Tourists visit the Royal Palace in Hsipaw, also known as East Haw. Built in the early 20th century, its architecture was greatly influenced by British colonialism. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

After her husband, Sao Oo Kya, a nephew of Kya Seng, retired from a government job, the couple moved into the palace in 1972. When the government started encouraging tourism in 1996, the couple opened the East Haw to small groups of tourists.

In 2005, Oo Kya was accused of being an advisor to a Shan political group banned by the junta and was sentenced to prison for 10 years, plus another three years for allowing visits to the East Haw without a tourism licence. He was released in 2009 under a general amnesty for political prisoners. The East Haw re-opened to tourists in 2012, a year after reforms began under the Thein Sein government.

“At the moment Hsipaw palace is the only palace still standing with family members living in it,” said Sarm Hpong.

Hsipaw has become a popular tourist destination because of the many Shan archeological sites around the town and opportunities for trekking to Shan and Ta’ang (Palaung) villages in the surrounding hills.

Sarm Hpong said it was unfortunate that many Hsipaw residents aged under fifty know little about the last Shan prince.

“It’s a shame for the town” if residents don’t know enough to answer the tourists’ questions, said U Ye Aung, 70, whose family was close to the royal couple.

“You have to know your history.”

Ye Aung was only eight when Kya Seng returned to his homeland but reflecting on those times as an older man said the young prince was “full of determination”.

The prince wanted Hsipaw to be much more developed and under his leadership “the area prospered from 1954 to 1962,” he said.

_dsf4092.jpg

Students wait to greet guests during a graduation ceremony at the Shan Youth Network English School. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

In an indication of the fear that prevailed among ethnic communities under military rule, Ye Aung told how he was able to obtain a copy of Sargent’s book three years after it was published in 1994 and gave it to the headmistress of a school.

“She took it up [inside] and locked the door; this shows how scared they were,” he said.

The boom in tourism since 2011 has seen an increase in the number of travellers visiting Hsipaw to learn about the town’s rich history. It was frustrating for Ye Aung that they often left with more questions than answers and in February he did something about it: He released a DVD that briefly explains Hsipaw’s history.

Of the 5,000 copies in English, Shan and Burmese, more than half have been sold. Proceeds from the sale of the DVD will go towards erecting a memorial statue of the royal couple in the grounds of the East Haw.

“If you come here the old sawbwas are lying there in tombs. So where is Sao Kya Seng? Where is he lying? There is no stone to mark [his grave],” Ye Aung said.

The government is yet to acknowledge Kya Seng’s death, or even that he was arrested.

After leaving Burma with her daughters, Sargent lived in Austria before returning to the US. Ye Aung said Sao Mayari and Sao Kennari, now past middle age, still write to the Myanmar government seeking answers about the fate of their father.

“Where is our daddy? When is coming back? Is he dead or is he still alive? Every year they are sending them,” Ye Aung said.

Title Picture: An early undated photo of Inge Sargent and Sao Kya Seng, the Shan princess and prince of Hsipaw. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)