This article was produced and sponsored by the Tat Lan programme.

Subsistence paddy farmers in central Rakhine are slowly adopting new techniques to boost yields and adapt to social and environmental changes, including an unpredictable climate and a shortage of casual workers.

By MOH MOH THAW | TAT LAN

Ko Kyaw San Tin is clearly excited as he prepares his paddy fields for the monsoon season.

Over the past 12 months, Kyaw San Tin has been receiving training on new cultivation techniques known as system of rice intensification (SRI) that have been introduced by Tat Lan, a programme sponsored by the Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund (LIFT).

Initially Kyaw San Tin was hesitant to use SRI. But after trialling the system last year and comparing the yield from SRI with that of traditional farming techniques, he is now so convinced of the benefits that he has rented an extra acre this year so he can use SRI across four acres in total.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“Last year I was afraid to take the risk of using all my farmland with the new technique. But when I cultivated one acre I found out that it saved a lot of money and labour, and the production was good too,” said Kyaw San Tin, who lives in Minbya Township’s Chit village.

Farmers in Minbya have traditionally used one of two methods to cultivate paddy: broadcasting seed or random transplanting. They are both expensive and low yielding, contributing to high levels of indebtedness and poverty in central Rakhine.

The cultivation cost ranges from about K170,000 an acre for broadcasting to K240,000 for transplanting. On this investment, farmers can expect a yield of anywhere from 60 to 120 baskets of paddy – provided the fields are not affected by extreme weather, such as a drought or cyclone.

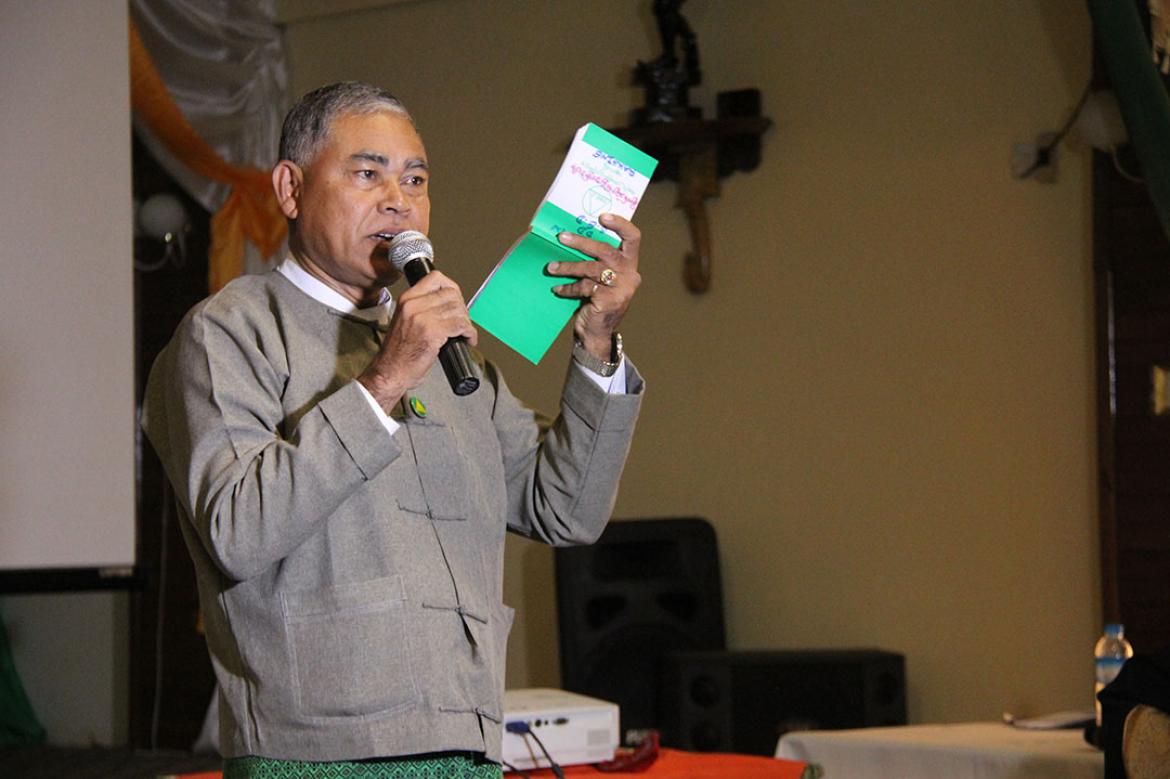

Farmers in central Rakhine State receive training from Tat Lan staff on how to choose the best seeds for their land. (Tat Lan)

In broadcasting, a large amount of seed is scattered across the farmland. This saves labour compared to transplanting but can require up to 200 tins of seeds per acre (a tin is the size of a condensed milk container). Random transplanting uses much less seed but requires as many as 20 workers, adding significantly to labour costs.

After planting, both methods present an additional challenge: clearing weeds. Because the paddy rows are close to each other, the only way to weed the land is by hand. But high outward migration from rural Rakhine State has significantly pushed up the cost of labour, making manual planting and weeding an expense that few can afford.

This presented an opportunity. If input costs – particularly seeds and labour – could be reduced, then farmers would be able to make more profit from their paddy.

Producing more with less

SRI has been introduced with success elsewhere in Southeast Asia and Tat Lan believed that if it was adopted in central Rakhine it could not only cut cultivation costs to about K120,000 an acre, but also increase yields.

SRI is a transplanting technique that leaves a gap of 25 to 30 centimetres (10 to 12 inches) between paddy plants to encourage free growth. The major tool required for SRI is a row marker, which creates a grid of small squares across the plot. Young paddy seedlings are planted only in the corners of each square. This saves both labour and seeds – because it is a more precise method of planting, SRI requires only 12 to 13 tins of seeds per acre.

Showing, not telling

While any technique that reduces input costs can have a big impact on farmers’ profitability, Mr Gerasmo Pono, manager of Tat Lan’s agriculture team, said it was still a major challenge to convince farmers to try new techniques like SRI.

“Generally, farmers have low levels of education. They don’t know what is going on or the latest updates about paddy production. There are traditional beliefs among farmers, such as that using ordinary seeds has the same output with using good quality seeds. So, we have to show them step by step how the new method works and compare the results with those grown in traditional ways,” he said.

Farmer Ko Maung Nge from Chit village in Minbya holds a tray of seedlings grown from good-quality seeds. Using the SRI techniques introduced by Tat Lan, Maung Nge will transplant the seedlings into his field. (Kaung Htet | Tat Lan)

In 2017, Tat Lan began introducing SRI through demonstration plots in Minbya and Myebon townships, working with farmers who were interested in adopting modern techniques. U Bo Kyaw Myint and his wife Daw Than Than Win, from Chaung Gyi village in Myebon Township, were among those who cooperated with the Tat Lan programme to experiment with SRI last year.

Another important aspect of SRI is using quality paddy seeds, as the seedlings grown from them are stronger than when poor quality seeds are used. For Bo Kyaw Myint and Than Than Win, the benefits of this were evident when Cyclone Mora flooded their fields at the end of May last year.

Although the flooding covered their land in debris and rubbish, the seedlings grown using SRI were still strong and healthy. To their surprise, each seedling produced 30 to 60 secondary plants, which are known as tillers. Ordinary seeds would normally produce around 20 tillers.

“I am happy to see the green paddy field and know that [Tat Lan’s] techniques are successful. Farmers in our neighborhood have come by to see the plot and say they really want to do something like this as well,” said Than Than Win.

This year, farmer Ko Maung Nge is cultivating one of his five acres as a demonstration plot in Chit village, Minbya Township. To support the planting of the SRI demonstration plot, Tat Lan provides some of the inputs and equipment, such as paddy seeds and fertiliser.

Plotting out the field with the SRI row marker means transplanting can be done by just a few people. A household of five, for example, can complete an acre of transplanting in around two days.

Until last year, Maung Nge used the line-to-line planting system, which requires two people to hold a length of rope from the top to the bottom of the field so that workers can transplant paddy along the line. Maung Nge said the system was not only labour intensive but also had other problems.

Ko Maung Nge demonstrates the use of a rotary hand weeder on his farmland in Minbya Township. (Kaung Htet | Tat Lan)

“Sometimes the line of string wasn’t straight so the lines of plants wouldn’t be straight either. And we didn’t leave much space between the lines. Now, when I use the row marker, the lines are straight and it is quicker to transplant the plants. I can do most of the jobs myself and don’t need a lot of labour anymore – that saves money,” 36-year-old Maung Nge said.

The new technique leaves wider spaces between the rows, which means the paddy is stronger and provides a higher yield. The wider lanes also mean Maung Nge can easily weed his fields with a rotary hand-weeder, saving more money on labour. The decomposed weeds then improve the quality of the soil and provide nutrients for the plants, which in turn leads to better growth and development.

“When farmers don’t have this kind of new knowledge, we rely on traditional ways. When I started using the new technique, other farmers around my farmland came and checked what I was doing. They were worried for me. Now, they see my land is going well and say that they will follow the new technique too,” said a visibly proud and happy Maung Nge.

Maung Nge is one of 35 farmers from four villages who participated in a seed production programme in 2018. A total of 10 farmers took part in the first year of the seed programme in 2016, but only two farmers were certified as seed producers. Tat Lan gained more success in the programme’s second year.

Farmers attend a seed selection training programme. Using good quality seeds can improve yields by five to 20 percent. (Tat Lan)

“For the year 2017 we trained another 21 farmer seed producers. This is the time that we started introducing the SRI method of paddy production, and all the 21 farmers passed the seed testing and produced certified seeds,” said Pono, the agriculture expert. “Certified or good quality seeds are very important to the farmers, and it could increase the yield between 5 and 20 percent.”

Government support

Experts from Rakhine State’s Department of Agriculture are helping Tat Lan to certify the seeds produced by the farmers.

Daw Win Win Naing, a staff officer with the agriculture department in Mrauk-U District, said she believed that SRI could deliver positive outcomes for farmers.

“Rural areas of Rakhine State are suffering from a shortage of workers. With SRI, farmers can grow the paddy just with their own family members,” she said.

Win Win Naing occasionally works together with Tat Lan to train farmers on how they can improve yields. She said that in her experience, farmers are unlikely to adopt new techniques unless they can see the benefits.

“Farmers won’t use new techniques just because you tell them it’s good, and they also can’t learn a lot at one time when you train them,” she said. “They are practical people, so the only way to introduce new techniques is to show them practically. They will change if they see the change.”