The 88 Generation Peace and Open Society movement has been a driving force for reform for nearly 30 years, and is likely to emerge as a powerful player in party politics.

By HEIN KO SOE | FRONTIER

ONE OF Myanmar’s most respected reform groups, headed by some of the nation’s most prominent veteran activists, is holding a meeting later this month that is set to shake up the country’s political landscape.

Leading members of the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society movement are holding a meeting in Yangon on March 30 to 31 to discuss the creation of a political party.

The group’s best-known activists include Ko Min Ko Naing, Ko Jimmy, Ko Ko Gyi, Ko Mya Aye, Ko Htun Myint Aung and Ko Marky – all of whom were prominent during the national uprising in 1988 from which their movement derived its name.

They were also prominent in the 2007 protests known as the Saffron Revolution, for which they were sent to prison. They regained their freedom during a mass pardon issued by President U Thein Sein in January 2012.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Not all will be involved in the effort to form a political party, a move that comes after nearly 20 leading 88 Generation members, including Ko Ko Gyi, were rejected by the National League for Democracy as party candidates ahead of the November 2015 election.

“Min Ko Naing and I will not be involved in forming the political party and the move is being led by Ko Ko Gyi and Ko Mya Aye,” Ko Jimmy told Frontier.

Min Ko Naing, an 88 Generation leader, talks during the opening of 8888 uprising silver jubilee ceremony at Myanmar Convention Center in Yangon, August 2013. (EPA)

Mya Aye said veterans of protest movements from 1962 to 2007 would be invited to the March meeting to discuss forming a party and to choose its name, slogan, manifesto and policies.

An organising committee, supported by five sub-committees, has been established to prepare for the meeting and it was hoped the party would be formed by the end of the year, Mya Aye told Frontier.

“We have never agreed with the 2008 constitution and amending or re-writing it will be the new party’s first priority,” he said.

Mya Aye said he and the other 88 Generation leaders involved in forming the party understood that its long-term survival would depend on voter support.

However, apart from changes to the constitution, the new party’s platform remains unclear. Mya Aye told Frontier it is not being formed to “fight” the NLD, but they will also not be supporting Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s party. Perhaps more will become clear after the March meeting.

Relations between the 88 Generation movement and the NLD were warmer in the past. In 2014, they worked together on a petition that attracted about five million signatures in support of constitutional reform. The petition sought to change Section 436, which stipulates that a constitutional amendment needs the support of more than 75 percent of the Union parliament. With Tatmadaw representatives guaranteed a quarter of all parliamentary seats, the military holds an effective veto over changes to the charter.

The prospect of a democratic reform party has been welcomed by key members of the NLD.

The NLD welcomed the prospect of “a new democratic alliance”, said U Nyan Win, a member of the ruling party’s central executive committee.

“They have the right to form a political party, and we can’t criticise them for that. They are well known by the people and they may get support from the public because of their political activities,” Nyan Win said.

A supporter holds an image of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi at a May 2014 rally to amend the 2008 Constitution. The event was jointly organised by the NLD and 88 Generation. (EPA)

He acknowledged that many of those who voted for the NLD in 2015 did so because of Aung San Suu Kyi, rather than the party’s policies, but said it has no concerns about a new party being formed.

“We are working to support our people so we are not afraid,” he said.

Nyan Win said he hoped a party formed by the 88 Generation movement would support the efforts of the NLD to transform Myanmar to a democratic federal state because such a development would benefit the population.

U Pike Htwe, a member of the central executive committee of the Union Solidarity and Development Party, and a deputy information minister in the Thein Sein government, said the USDP was not concerned by the prospect of the 88 Generation group forming a party.

“It’s the voters who decide and we are focusing our attention on our voters, so we have nothing to be afraid of,” he told Frontier. “Myanmar people voted for a famous figure. Voters don’t know about the constitution, or the need to re-write it. They are only concerned with their livelihoods,” he said.

Swedish journalist and author, Mr Bertil Lintner, who has written extensively about Myanmar, echoed Pike Htwe’s assessment.

“In 2015, and in 1990 as well, the people voted for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, sometimes without knowing who the local candidate was,” Lintner told Frontier.

The situation arose partly because the political landscape in Myanmar was polarised with little or no room for “third parties”, he said.

“This may not change as long as the military remains the most powerful institution in the country and people want to change that,” Lintner said.

“On the one hand, more political parties are needed to make democracy work, but, on the other, more pro-democracy parties would split the anti-military/USDP vote; it’s a dilemma and will take years before Myanmar is a functioning parliamentary democracy,” he said.

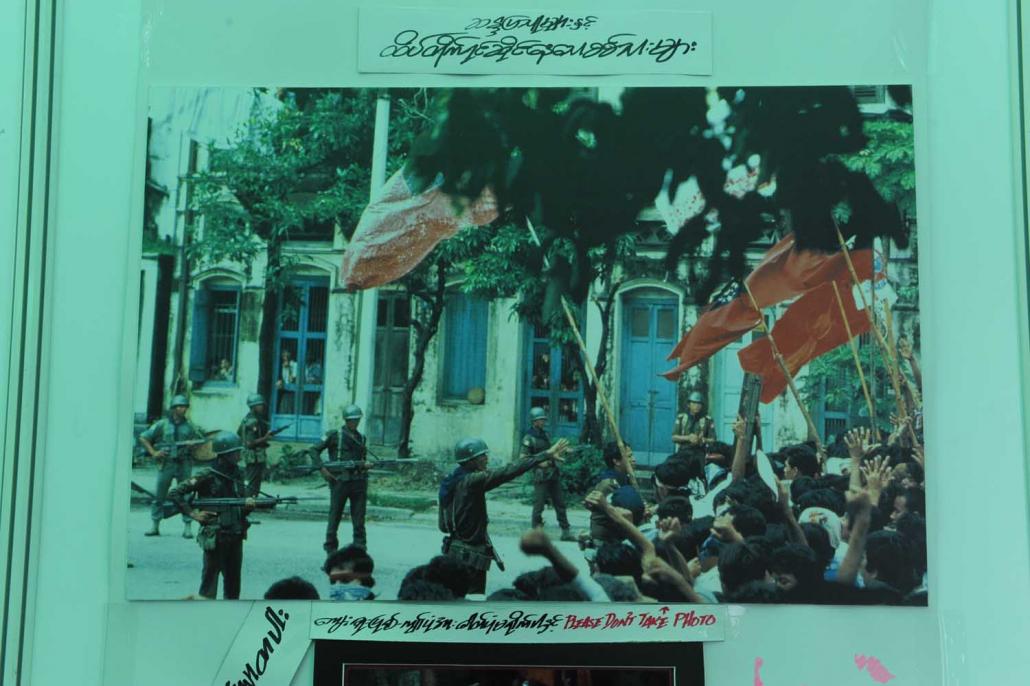

A photo on display at an exhibition to commemorate the 1988 uprising at the 88 Generation headquarters in Yangon’s Thingangyun Township. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Lintner said one of Myanmar’s problems, historically, was that when it has had many political parties, one was almost always likely to be dominant.

He noted that in the 1950s, when Myanmar had a multi-party system, it was dominated by the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League and there was almost no opposition in parliament. “In fact, the media functioned as the unofficial opposition through its interviews with the Prime Minister at the time, U Nu,” he said, adding that after 1962 only the Burma Socialist Program Party was allowed to operate.

In the 1990 election, the NLD won 392 out of 485 contested seats, but was not allowed to form a government, and the 2010 election was boycotted by the NLD, making the USDP the predominant political party in parliament, until 2015 and the NLD’s landslide victory.

“What Myanmar needs for democracy to function is a wide range of political parties representing different ideas and ideologies but given the polarised political situation in the country that will be difficult to achieve,” Lintner said.

“In my view, even the 2015 election was more of a referendum than an election where people voted for different parties,” he said, noting the party’s success in ethnic minority areas where the party is not traditionally popular. “People voted for the NLD anyway because [they] wanted to get rid of the old system,” he said.

U Khin Zaw Win, director of Yangon-based Tampadipa Institute, said he has been urging 88 Generation members to be involved in politics since before 2010.

“The 88 Generation relied heavily and pinned their hopes on joining up with the NLD, but just before the 2015 elections the door was rudely slammed in their face,” he said, a reference to the fact that none of the group’s members were chosen as candidates. “If they form a party now, a rule of thumb is: just do things differently from the NLD and you can’t go wrong.”

He also rejected the view that a new party formed down democratic lines would split the vote, potentially strengthening the position of parties like the USDP, dismissing that view as “inaccurate, misleading and fear-mongering” by NLD supporters. “I’d even say the vote has to be split,” he said.

U Aung Moe Zaw, chairman of the Democratic Party for a New Society, which was formed by student activists in the aftermath of the 8-8-88 Uprising, said that Myanmar needs a political party that has strong policies, and not just reliant on a figurehead to gain votes.

“I hope the 88 Generation will be like this,” he said.

TOP PHOTO: Ko Ko Gyi of the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society speaks at a press conference in Yangon in June 2015, shortly before the NLD decided not to select him run as one of its election candidates. (EPA)