Project delays and rising demand have created a power supply crunch, and the government is considering costly emergency measures to avoid blackouts in an election year.

By KYAW YE LYNN and THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

West of the downtown area, across the Yangon River, there’s a narrow spit of land that ends at the mouth of Twante Canal, with the island of Seikgyikanaungto to the west.

For a brief period nearly three years ago, this site was to be the home of a power plant. It remains empty except for a huge transmission tower with high-voltage lines that span the river, and a concrete road that runs parallel to the shore. The area that was cleared for the plant is now overgrown, the hard-packed brown soil hidden beneath scrub and weeds.

The site is symbolic of the indecision, lack of planning and government dysfunction that have conspired to create crippling power shortages in Yangon and other parts of the country this year.

In July 2016, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy called a tender for a five-year contract to install 300MW of emergency generation capacity close to Yangon, beginning the following year. The winner – a consortium comprising United States-based APR and Myanmar’s National Infrastructure Holdings – had planned to build a plant beside the river powered initially by diesel and then heavy fuel oil.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The government also contracted a second company, Turkey’s Karpowership, to provide another 300MW of extra capacity. In November 2016, the company flew Myanmar journalists to Istanbul for the launch of the Karadeniz Powership Onur Sultan, which it dubbed the world’s largest floating power plant. Officials told the Myanmar Times that the ship, which had a Myanmar flag painted on its hull for the launch, would arrive in Yangon by the following April.

And then the projects died a quiet death.

Frontier understands that the Ministry of Planning and Finance was unwilling to pay the inevitably high price of the short-term emergency power contracts, and refused to include the cost in the budget for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2017.

Instead, Myanmar turned to longer-term options that would be powered by imported liquefied natural gas. But with these proposed projects facing delays, the country again finds itself in a position where it is considering emergency power projects – only this time it needs more, and sooner.

That means the solution will be even more expensive than three years ago. But the lack of other projects in the pipeline means there are few alternatives if the government wants to avoid serious power shortages in the years ahead.

Planned cuts

On May 22, medical staff at a public hospital in Pyin Oo Lwin Township, Mandalay Region, gave about a dozen patients the good news: their surgery had been scheduled for the next morning. To prepare for the operation, the patients were told not to eat or drink after midnight.

Expecting that he would be in surgery for up to 10 hours the next day, Dr Tayza Kyaw, a senior consultant orthopaedic surgeon, declined a dinner invitation from a friend that night.

At first the operations went well, Tayza Kyaw wrote in a Facebook post later on May 23. But around noon, with three patients about to undergo surgery, the power suddenly went out. The hospital’s small backup generator could not provide enough power for crucial equipment, such as the C-arm that produces X-ray images mid-surgery.

“I even called to the EPC,” he wrote, referring to the Electric Power Corporation, the former name of the Electric Supply Enterprise. “But the staff there had no answer. They just said supply had been cut from the national grid … so we had no idea what to do.”

The doctors, nurses and patients waited for hours for the power to return. Finally, they had not choice but to postpone the operations. The experience left Tayza Kyaw frustrated.

“Steady power supply must be provided to public hospitals,” he wrote.

Frontier was unable to reach Tayza Kyaw because he was travelling abroad, but his wife confirmed the events in the Facebook post.

Such unplanned, unscheduled outages were once the norm in Myanmar, but since 2011 electricity supply has improved dramatically – at least for those lucky enough to be connected to the national grid.

The completion of the country’s largest power plant, the 790MW Yeywa hydropower project, in 2010 and a series of smaller, mostly gas-fired projects overseen by the U Thein Sein government added significantly to Myanmar’s generating capacity. Upgrades to transmission and distribution systems helped to increase efficiency.

But rising demand and a lack of new generating capacity in recent years has again stretched the system to – indeed, beyond – its limits. The crunch has come at the tail end of the hot season, when demand peaks and many hydropower projects are unable to operate at full capacity due to a lack of water.

When demand exceeds supply, the Electricity Supply Enterprise and the Yangon and Mandalay electricity supply corporations turn to load shedding of the kind experienced in Pyin Oo Lwin on May 23. These are deliberate power cuts to certain cities, townships or neighbourhoods in an effort to get supply and demand back into balance.

After the Thingyan festival, load shedding began to increase. In Yangon the situation was so dire that on May 4 a schedule for power cuts was introduced and publicised on social media, with supply to industrial zones prioritised during business hours and residential areas in the morning and evening.

But these outages should be considered in a broader perspective. Yangon, Nay Pyi Taw and Mandalay are generally protected from the worst of the power cuts, which are focused instead on mid-sized cities and rural areas. Schedules have been introduced in many of these areas, too, just with longer planned outages.

While it is unclear when normal delivery will resume, opting for planned outages over ad-hoc load shedding appears to have helped dampen much of the public irritation over the power cuts.

“Our area suffers a blackout every three hours, but it generally follows a schedule,” said Ko Nay Min Han from Mandalay’s Maha Aung Myay Township. “The blackout lasts a maximum of one hour but it’s predictable so it’s easy to work around it … the random blackouts that we faced in the past made our life, our work – everything – difficult.”

Ko Zaw Zaw Htet from the Ayeyarwady Region capital, Pathein, said the schedule had made it much easier to operate his furniture business. The town has been divided into four distribution zones, with power cut to one zone at any one time.

“When it’s predictable, we can manage our business. The schedule is much better,” he said.

But he noted that residents were still also facing some unscheduled outages, and these had become more frequent in recent weeks.

“Luckily, these power cuts usually last no longer than an hour. I really don’t like these random blackouts,” he said. “But I can honestly say that the electricity supply has improved compared to the previous years.”

typeof=

A predictable outcome

This year’s power shortages were entirely predictable – in fact, they were predicted two years ago.

Myanmar relies on a combination of hydropower and gas-fired plants. Most of Myanmar’s domestically produced gas is exported under contract. With production expected to decline from 2020, there is little room to expand the use of gas-fired plants until new fields come online.

Although power supply should improve after monsoon rains begin to refill the dams that provide water for the country’s hydropower plants, the cuts will worsen in the years ahead unless new generation capacity comes online.

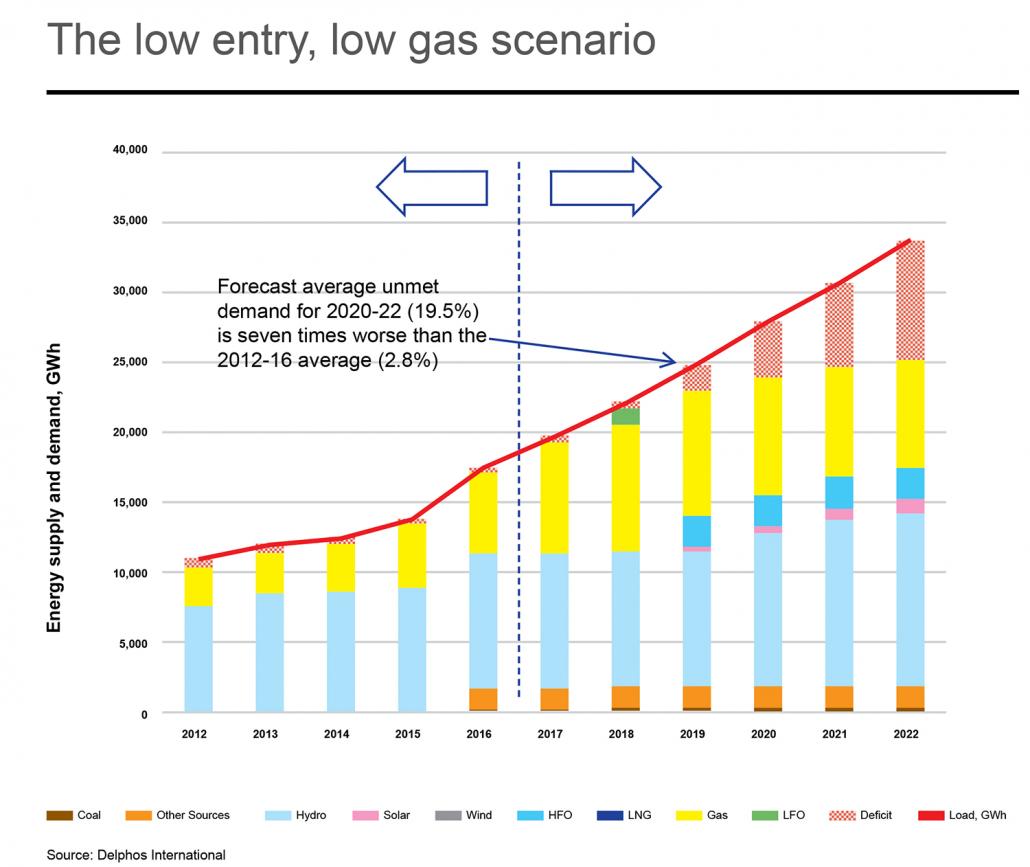

A short-to-medium term supply/demand analysis prepared for the Ministry of Electricity and Energy in June 2017 under a project financed by the United States Trade and Development Agency outlined several scenarios for meeting energy demand to 2022. The analysis was prepared in close collaboration with the ministry, and was based on the latest data regarding electricity supply and demand.

The worst-case scenario was described as “low entry, low gas”: little new supply, and a delay to the development of the M3 gas field in the Gulf of Mottama.

From 2020 to 2022, this scenario would result in 19.5 percent of electricity demand going unmet – in other words, one in every five times you go to switch on the television, you’ll instead end up reading a book by candlelight. These energy losses, which the analysis described as “extreme”, would be seven times worse than the average from 2012-16, it said.

But what Myanmar faces is worse than the worst-case scenario in the analysis.

The “low entry, low gas” model anticipated 300MW of extra supply generated from light and heavy fuel oil coming online from 2018. This never materialised because the government backed out of the 2016 emergency power tender.

The USTDA-funded analysis proposed three projects – one LNG-to-power, one solar and one diesel generator – to soften the impact of looming shortages. The World Bank had proposed a different LNG option: a tender for a medium-sized onshore terminal that would feed gas to state-run and private power plants around Yangon.

Instead, though, the ministry issued “notices to proceed” in January 2018 to the sponsors of three larger LNG-to-power projects: Supreme and Zhefu Holdings of China to develop a 1,390MW project at Mee Laung Gyaing in Ayeyarwady Region; Total of France and Siemens of Germany for a 1,230MW project at Kanbauk in Tanintharyi Region; and Thai company TTCL to develop a 356MW plant. Ambitious deadlines were set for the projects to come online, with the first generation due to be ready just before next year’s election.

These projects have fallen well behind schedule, with the sponsors and the government unable to agree on financial terms and sign power purchasing agreements. The key stumbling blocks are the currency of the PPA, requests from the developers for a sovereign guarantee to ensure they are paid what they are being promised in the PPA, and the overall financial risk that Myanmar would assume if it proceeds with these deals.

(In our next issue, Frontier will examine the prospects for these three LNG projects and take a closer look at the reasons for the delays.)

Other planned power projects, such as a series of small and medium-sized hydropower plants, have faced delays for similar reasons.

“Power demand is increasing very fast and the supply position during hot seasons is going to be a problem,” confirmed a development sector official. “The ministry has not prepared a sustainable plan using available advice from several development partners … the government needs to ensure projects are selected under a least-cost plan and not in an ad-hoc manner.”

At the same time, demand has been increasing faster than anticipated, according to multiple sources; the USTDA-funded study forecasted demand growth of 12pc, but in early March Minister of Electricity and Energy U Win Khaing was quoted as saying that demand was increasing at 15pc to 19pc a year.

This rising demand is partly due to the expansion of the national grid. With assistance from the World Bank, grid access has been increasing at 10pc to 12pc a year, and the government expects to have half of all households connected before the end of the year, and 55pc by the end of March 2021. Mr Sunil Khosla, lead energy specialist at the World Bank, said demand would “increase over time” as those newly connected households buy more and more electrical appliances.

Given this higher-than-expected demand, the outages this year have not been as widespread as some anticipated.

“In the circumstances, the ministry has actually done a pretty impressive job to minimise outages,” said a source close to the ministry. “I expected it would be much worse.”

Under pressure

“It could have been worse” doesn’t work well as an election campaign slogan, though.

In recent months, as the delays to the LNG projects and the looming power shortages became clear, the government has been putting greater pressure on the ministry to come up with a viable alternative plan, multiple sources told Frontier.

Questions are also being asked directly about Win Khaing’s leadership, particularly his decision to issue the notices to proceed for the three LNG projects, rather than seemingly safer options.

“The minister was very hopeful about the NTPs but now realizes these projects are failing. It’s a personal failure for him – he put all his eggs in one basket,” said an industry source.

Another added, “If you just look at these projects, it was quite an obvious conclusion that the original plans were massively overoptimistic. There was no way they were ever going to meet the original timelines.”

But others note that Win Khaing is “taking it in both sides of the neck” – on the one hand, he’s under pressure from senior levels of the government to find a solution, yet at the same time he’s getting little cooperation from other ministries to ensure that any of the LNG projects he has backed move forward.

U Han Zaw, deputy director general of the Department of Electric Power Planning, confirmed that the ministry was under pressure from the government to come up with solutions to the power shortages.

“It is our responsibility to find ways to prevent blackouts like these in the future,” Han Zaw told Frontier.

“We are like most farmers in Myanmar – we depend largely on rainwater,” he said, referring to Myanmar’s reliance on hydropower. “We have to change it … We need to diversify into other sources.”

The priority now is to have additional power generation capacity in place by next hot season. It is, after all, an election year, and State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been vocal about her government’s focus on delivering roads and electricity to rural communities. Faltering power supply threatens to undermine that narrative.

Speaking at the opening of a 145MW gas-fired plant in Kyaukse, Mandalay Region, on May 17, Aung San Suu Kyi said that since taking office the government “has realized that the two main tasks for the development of the country are transportation and electrification”. “If our country’s people get access to good transportation and electrification, their socio-economic life will improve quickly,” she was quoted as saying.

The gas-fired plant at Myingyan developed by Singaporean firm Sembcorp is one of the few power projects to open under the National League for Democracy government. (Supplied | Frontier)

The (latest) power plan

In early May, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy suddenly changed tack, announcing a range of potential short-term solutions to the power shortages, including LNG barges, importing power from China and Laos, and solar photovoltaic projects.

Officials said they plan to call a tender for about 1,400 megawatts of additional capacity to be supplied from barges in three potential sites: Thilawa in Yangon Region, Pathein in Ayeyarwady Region and Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State. The barges would generate power from LNG.

Han Zaw said the tender will be announced by early July so that there is enough time to select the winner and have barges in place for next hot season.

He added that the government had already given verbal approval to the plan and the ministry was just waiting for the “paperwork” to be concluded.

Han Zaw said the ministry would speed up the tender process by essentially making it invitation only. Unsolicited bids will only be considered from high-profile companies or consortiums, he added. “We will selectively invite high-profile companies to avoid wasting time.”

The ministry is also considering buying electricity from China and Laos to alleviate shortages. At a press conference earlier this month, deputy permanent secretary U Soe Myint said the ministry would buy “1,000MW” over the next two years under a proposal from China Southern Power Grid.

However, Han Zaw said that negotiations were continuing between the ministry and companies from both countries, with no deal yet reached.

The lack of a high-voltage transmission line to Yangon meant that power imports from China or Laos would initially be used to supply border areas, such as Shan or Kachin states, rather than the national grid.

“By doing this we can reduce power losses and avoid the construction of a high-voltage power transmission line,” he said.

The ministry is also planning to issue a call for expressions of interest for on-grid solar PV projects ranging in size from 100MW to 200MW.

One key advantage of solar projects is that they can be installed relatively quickly – in as little as six months to a year.

“Actually, we just want small-scale solar projects with electricity productivity of up to 100MW because we think it will be easier to attract investment,” he said.

However, the ministry will consider proposals for projects up to 200MW because production will reduce during rainy season when there is less sunlight.

PR stunt or practical solution?

Will these plans address Myanmar’s short-term energy needs?

Of the three options proposed, only power barges are likely to be able to avert significant shortages next hot season, particularly in Yangon.

The lack of a high voltage transmission line connecting China and Myanmar means that imports would initially be limited to border areas.

This would free up some power for transmission to major demand centres, but there is another catch. Most of the demand is in Yangon – about 40 percent of the total, based on recent government figures – while most generation occurs in northern Myanmar. Electricity is sent to Yangon on a 230kV transmission line, which results in high transmission losses and regular outages. A 500kV line linking Yangon with Meiktila in Mandalay Region that would enable power to be transmitted to the south of the country more efficiently is being installed, but is unlikely to be ready for at least two to three years.

More broadly, there’s also the cost of importing power to consider. Although the price of power in China varies depending on the customer and region, it’s generally well above K100 a unit.

Solar has the advantage of being fast, but it’s unlikely to be fast enough to come online before next March or April.

The barge plan also faces a range of challenges. In a client briefing note, legal advisory firm VDB Loi noted that the timing of rental power contracts in Myanmar was usually relatively tight, and failure to meet deadlines can result in the Electric Power Generation Enterprise charging daily damages. Financing options are limited and EPGE has increasingly been pushing for payments to be made in kyat, which is unattractive to investors. Rental power projects technically also require an Environmental Compliance Certificate from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, while for barges an ad-hoc licensing procedure would likely have to be negotiated with the Department of Marine Administration, VDB Loi wrote.

The spectre of the election does seem to have galvanised political will to get a deal done. But getting barges in place by next hot season would require a level of government coordination and streamlining that has been absent until now – as the failed 2016 emergency power tender shows.

Mr Guillaume de Langre, energy research manager at the International Growth Centre, said there weren’t many options left on the table to fill the gap between now and the mid-2020s.

Renewables, particularly solar, could make a difference, particularly given prices are falling rapidly and plants could be built close to demand sources. He added that “almost two dozen formal and informal proposals” had been submitted to the ministry for renewables projects. Other measures that could “lessen the blow” include better controls over demand and efficiency, building interconnections with neighbors and bringing prices to levels where customers monitor their consumption.

“The big picture is that there is a growing risk that power cuts will have significant effects on growth and development,” de Langre told Frontier. “Not only on how much the economy grows, but where. Areas with better quality of supply might grow faster and attract more productive businesses, which could exacerbate the [already existing] divide.”

typeof=

Paying the price

Even if the LNG barges steam in to Yangon by next March, there’s another problem: paying for the electricity they generate.

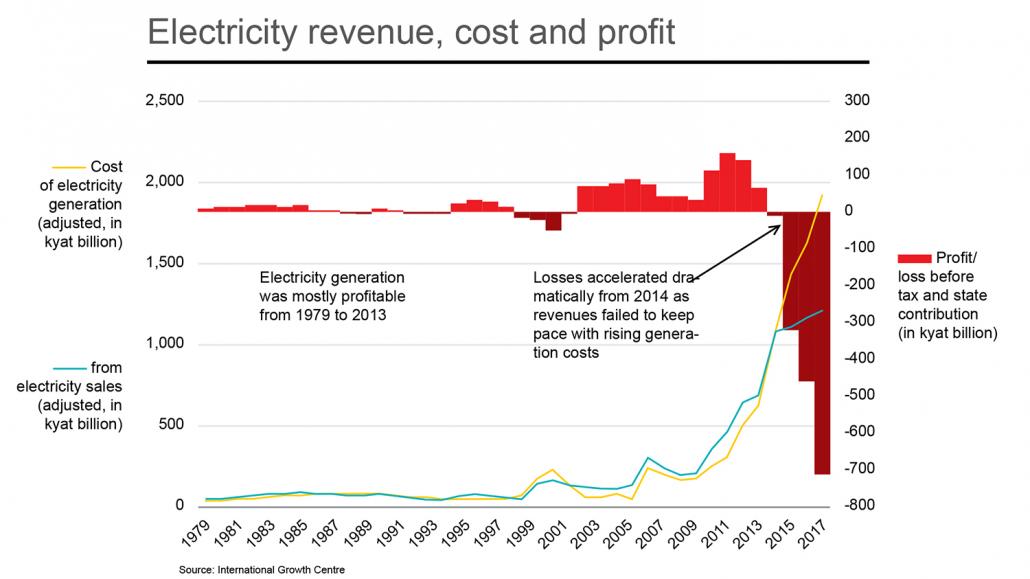

Electricity supply in Myanmar is heavily subsidized, particularly for home users – the K35 to K50 per unit (1 kilowatt hour) that they pay is thought to be among the lowest in the world. Prices have not risen since 2014, despite a growing reliance on power from more expensive, privately run operations.

Writing in the Myanmar Times last year, de Langre said that by early 2018 the average cost of supplying 1kWh had risen to K108 – more than three times the lowest tariff that home users pay.

As a result of these subsidies, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy is expected to lose K630 billion in the 2018-19 financial year. Left unaddressed, these subsidies will balloon to more than K1.5 trillion annually in the years ahead as demand rises and more power projects come online, said de Langre.

Mr Sean Turnell, an economic adviser to Aung San Suu Kyi, said the government’s prudent fiscal management had created the opportunity for a “fiscal stimulus” in 2020 that could include electricity.

“We’ve almost been a little too successful in turning the whole fiscal situation around, so there’s room to spend,” he said, without referring to specific projects. “The country’s infrastructure needs are off the scale and there’s broad acceptance that the government can and should spend a bit more … and electricity is needed more than anything else.”

Asked about the tariff, Han Zaw from the Ministry of Electricity and Energy was unequivocal: prices would need to rise before the government can move forward with plans to meet demand for next hot season.

“First things first. All these plans will only be [possible] after an electricity price increase,” Han Zaw said. “Buying electricity from other countries or generating power from LNG plants will cost at least K100 [a unit]. That’s about three times the current [base residential] rate … so a price hike is inevitable.”

The ministry has been working on a revised tariff regime for more than a year, and has had a plan ready to go since December, Frontier understands, but the government has delayed introducing the new rates.

“Almost everything is ready. What we need is the green light from someone,” said a senior official, in an apparent reference to State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

“Wet season provides a possible window as the power supply position will improve,” said an industry source. “If the government doesn’t do it then, the issue will slip because it will be harder to raise prices when supply is poor and when elections are close.”