The separation of Burma from British India is often overshadowed by a more violent partition 10 years later, but it was a moment that had a significant impact on this country’s modern history.

By GEORGE KENT | FRONTIER

THIS YEAR marks the 80th anniversary of the separation of colonial Burma from British India. Despite the significance of this event, the anniversary has largely faded from popular consciousness and been overshadowed by the violent events of the partition of India in 1947.

Following the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885, Upper Burma was annexed and the country became a province of India, ruled from Calcutta. This led to a growing resentment towards India, not only among the Burmese population, who opposed foreign rule, but also British and other foreign interests who wanted Burma run as a separate colony.

Support for Burma as a separate entity emerged shortly after annexation. Sir Frederick Fryer, the Lieutenant-Governor of Burma from 1897 to 1903 – prior to that governors held the lower rank of chief commissioner – believed that Burma was just as fit for governance as India. He also noted that the Burmese, in their religion, race and habits, were different from Indians.

Simon Commission

But the question of separation was only thoroughly examined in the late 1920s. The Indian Statutory Commission, led by Sir John Simon, was sent to Burma in January 1929 to review the political structure put in place in 1921, when the diarchy system was introduced through an extension of the Government of India Act to Burma.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

In 1930, the Simon Commission recommended the immediate separation of Burma from India but there was no clear political consensus to do so among the British, Indian and Burmese forces within Burma. Fierce debates occurred between separatist and anti-separatist factions, with topics ranging from immigration and the economy to inherent distrust of the British.

Immigration issues

When Burma became a province of India, many people from across the Indian Empire took the opportunity to migrate. By the late 1920s, Rangoon was said to be one of the busiest ports in the world for immigrants, second only to New York. This increased migration was the main target of many pro-separatists and nationalists.

In his correspondence with the British Secretary of State for India, Sir Samuel Hoare, the president of the Burma Free State League, U Ba Si, criticised what he described as the colony’s “open door” immigration policy. In 1933 he wrote: “Since the annexation of Burma by Britain, thousands and thousands of destitute Indians have come over to our shores to exploit our labour and lands.”

Such proclamations by nationalistic separatists concerned many Indians living in Burma. They grew increasingly alarmed at the rising anti-Indian sentiment among the educated classes. “A Burman as a whole is friendly to non-Burmans,” said lawyer P D Patal. “There are a few educated Burmans who in season and out of season think it their duty to shout loudly that Burma is for Burmans only. Fortunately, it is a small section.”

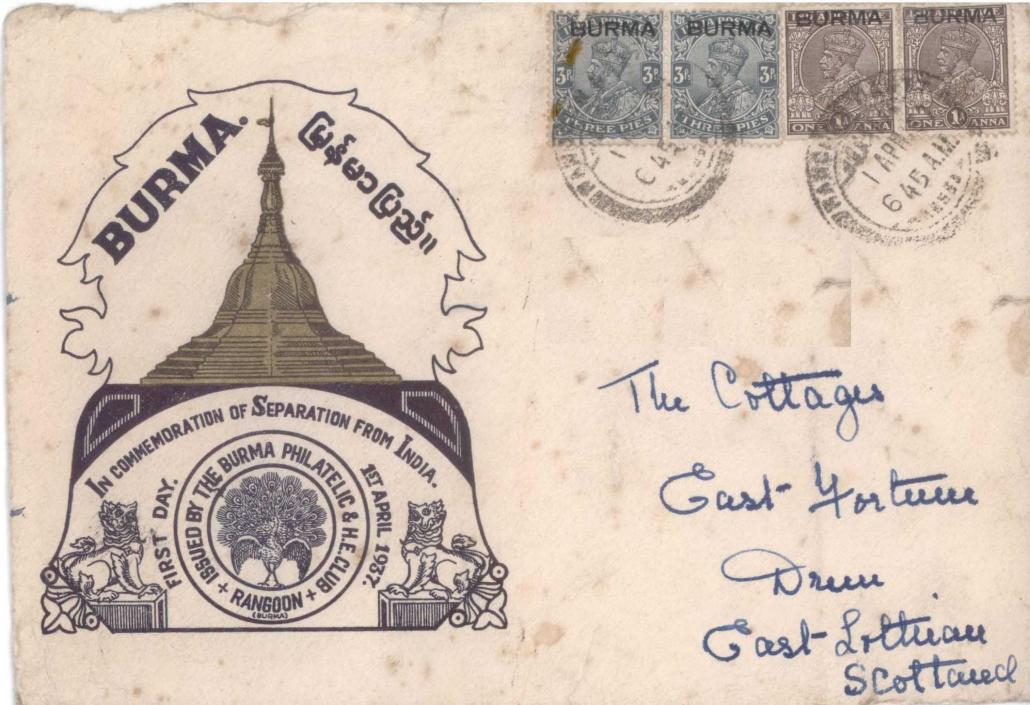

myanmar_-_1937_.jpg

A commemorative ‘first day’ issued by Burma’s postal service to mark separation from India on April 1, 1937. (Wikimedia Commons)

A popular Indian view emerged that the Burmese were forming a plan to kick all non-Burmese out of the country. For this reason, many demanded that Burma continued to be part of the Indian Empire unless there was a guarantee that there would be no discriminating legislation.

However, not all pro-separatist groups focused on immigrants from India. The Anglo-Burman and Domiciled European Community of Burma stated that they wanted separation from India so that the country could create an immigration act to “keep out undesirable aliens”. These organisations were more concerned about Chinese migrants arriving in Burma.

Organisations representing minority interests also had their differing opinions towards the separation. In the Burma Muslim Community’s memorandum to the Statutory Commission, the group conveyed reservations towards separation due to rising Burmese nationalism. The community protested about being called “kalars” – a pejorative term for foreigners, particularly from South Asia – within certain circles.

They expressed concern that a new separatist government would withdraw their rights and label them foreigners. However, the group also stated that it would not stand in the way of a majority wanting separation.

The economic arguments

The impact that separation would have on Burma’s economy was another topic of heavy contestation. A view held by many Burmese and British officials was that the economy would benefit from separation. A pamphlet written by barrister U Mya U in 1928, titled “A Plea for Separation of Burma from India”, claimed that because Burma was a province of India it lost 68 million rupees each year in revenue – a sum equivalent to 63 percent of total revenue in 1927-28. The author complained that Burma’s revenue was being used to support regions as far away as the North-West Frontier Province, in modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan.

British commercial interests in Burma also viewed the separation as being positive for the economy. This view claimed that Burma was restricted by trade tariffs set by the Indian Government and the inability to create their own trade policy was detrimental to the economy of the province.

On the other hand, a variety of businesses in Burma and India believed separation would be detrimental to Burma’s economic interests because the two economies were heavily entwined, and Burma would be expected to bear the direct costs of separation. The Indian government, for instance, would likely demand payments to compensate for the railways it had built in Burma.

sao_shwe_thaik_and_hubert_elvin_rance.jpg

Burma’s Independence Day. The British governor, Hubert Elvin Rance (left) and Burma’s first president, Sao Shwe Thaik, stand at attention as the new nation’s flag is raised on January 4, 1948. (Wikimedia Commons)

British support for separation complicated the situation and boosted distrust among Burmese circles, leading to the establishment of the Anti-Separation League in July 1932. Led by Dr Ba Maw, his supporters believed that separation was a British ploy to undermine Burmese political advancement towards independence.

Stories were spread that Burma would be left to the mercy of the British government, with extra taxation and an increase in “undesirables” from other British territories – a reference to the unemployed and destitute, and another example of anti-immigration rhetoric being employed in the debate but this time in an anti-separation context.

The general election of 1932

Political parties that had joined either the anti-separatist or separatist politicians went head to head in the 1932 general election, which was seen as a poll of public opinion on the separation issue. It was assumed that the Separation League would win, but neither side achieved a 45-seat majority. The Anti-Separation League won 42 seats compared to the Separation League’s 29. Burmese separatists claimed that money from wealthy Indians had been used to push pro-federation propaganda. Meanwhile, British officials claimed that separatists were too confident of victory and had failed to campaign actively in rural areas.

Foundations of modern Myanmar

The election outcome did not result in a change to policy. The British feared that if they didn’t separate Burma from India, there would be anti-Indian unrest on a larger scale than the riots of 1930, in which hundreds were killed.

The Government of Burma Act 1935 confirmed that separation would occur on April 1, 1937, ending 51 years of the country being ruled as a province of India.

The act laid the foundations for Burma’s post-independence political system, with the establishment of a Westminster model of cabinet with nine Burmese ministers alongside an elected House of Representatives. The former anti-separatist Dr Ba Maw served as the first chief minister to Burma after separation.

The successful and peaceful separation laid the political foundations for Burma to become an independent state, but the emphasis on anti-immigration rhetoric during the campaign for separation contributed to the rise of Burmese ethno-nationalism that would have implications for the country in the decades ahead.

TOP PHOTO: Boats along the Rangoon River. In the late 1920s, the city’s port is thought to have been one of the busiest in the world for migrants, behind only New York. (Wikimedia Commons)